At 10.45am on Wednesday 15 March, an explosive email landed in the inboxes of all of Anthony Albanese’s cabinet ministers.

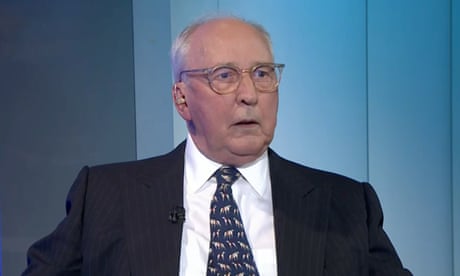

“Dear cabinet colleagues,” wrote Paul Keating, the Labor luminary turned chief Aukus critic.

“My views will not please the prime minister, the foreign minister nor the defence minister but the country is entitled to a rationale for such a radical and dangerous policy.”

The purpose of the email was to forewarn ministers that he would be tipping a bucket on them – and the nuclear-powered submarine plan they had endorsed – when he fronted the National Press Club in Canberra two hours later.

Never one to mince his words, Keating gave the cabinet a taste of some of his most blistering lines against the Aukus deal announced by Albanese in San Diego just the day before.

This included Keating’s claim that “the government’s complicity in joining with Britain and the United States in building nuclear submarines for Australia is the worst decision any Labor government has taken since the government of Billy Hughes sought to conscript Australian men and women for service in world war one”.

In the 300-word email, obtained by Guardian Australia under freedom of information laws, Keating also warned ministers that the “off the scale” plan to spend up to $368bn on nuclear-powered submarines would “seriously maim the budget and jam all manner of social spending into the foreseeable future”.

“The decision to proceed down this path is terrible,” the former prime minister wrote. “In my view, the proposal is uncalled for and given its huge expense and concomitant lack of explanation – an affront to public administration.”

Keating notified ministers he was going to release a public statement at the same time as the speech, “a copy of which I have attached here for your benefit”.

He signed off: “Yours sincerely, Paul Keating”.

Sure enough, when he addressed the National Press Club later that day, Keating took aim at Albanese and his most senior ministers.

Keating ridiculed the foreign affairs minister, Penny Wong, for “running around the Pacific islands with a lei around [her] neck handing out money”, and said the defence minister, Richard Marles, was “completely captured by the idea of America”.

Wong responded to Keating in April by stating: “I think in tone and substance he diminished both his legacy and the subject matter.”

But the 15 March email to all ministers was not the first time Keating had sought to raise concerns directly with the upper echelons of the government.

Guardian Australia has also obtained a paper titled “Aukus, Australia and China” that Keating sent to the prime minister. It was dated 24 January, seven weeks before the San Diego announcement.

In the paper, also released after an FOI application, Keating said China’s ability to take Taiwan and control the South China Sea was “undeniably growing”. Keating contended that China was “now capable of challenging American military primacy in East Asia”, meaning Washington’s ability to move its forces at will.

“It is the potential loss of that primacy that has caused Washington’s rapid policy shift towards military and economic containment of China,” Keating wrote.

“Even so, the chance that the US will be able to preserve strategic primacy in East Asia, while protecting its critical interest in Europe and Nato, is fading.”

But Keating argued China would “always be surrounded by a group of strong large and middle powers - Japan, India, Vietnam, Korea, Indonesia and Russia” and would “never be free to do as it pleases”.

after newsletter promotion

Keating said Australia’s interests were well-served by a close relationship with the US, because that enabled Canberra to have political influence in Washington and access to advanced weaponry and intelligence.

“But Australian and US interests are different. You don’t need to be a conspiratorialist to acknowledge that powerful industry and national forces are pushing for Australia to go in one direction.”

Keating argued Australia’s capacity to protect its sovereignty would be found in a broad diplomatic and security effort with its Asian neighbours to give the region the resilience it wanted and the economic growth it needed.

He said the Morrison government’s Aukus announcement in 2021 was “structured and presented” in a way designed to draw Australian and US forces closely together.

But Keating warned: “Designing Australia’s future defence force around the objective of deterring China, principally from an invasion of Taiwan, by means of integrating Australian defence assets into those of the United States is contrary to our interests. It constrains Australian decision-making and shreds its sovereignty.”

Keating pointed to “growing dysfunction” in the US political system. For the first time in 70 years, he said, Australia “can’t be confident that the general direction of US grand strategy will remain unchanged over the next eight years”.

“Australians have glossed over our role in Washington’s poor decision-making since the end of the cold war, convincing ourselves that the contribution we made was minor. But we can’t let ourselves off the hook. We have to be sure that we are not again standing by while major and dangerous decisions are being made.”

Albanese, Marles and Wong’s offices were all offered the opportunity to respond on Wednesday but did not provide any new comments.

The prime minister has previously said he retained “utmost respect” for Keating’s achievements but disagreed with his predecessor’s “attitude towards the state of the world in 2023”.

Albanese has repeatedly said Australia is investing in relationships across the Indo-Pacific region, in addition to investing in defence capabilities.

The government says Australia will maintain sovereign control of the new submarines and that it wants to contribute to a balance in the region that ensures “the risk of conflict will always far outweigh any potential reward”.

In a speech in Singapore last Friday Albanese warned against “harmful” assumptions that the US and China were heading towards an inevitable war and called for dialogue and “practical structures to prevent a worst-case scenario”.

“Australia’s goal is not to prepare for war but to prevent it, through deterrence and reassurance and building resilience in the region.”