风萧萧_Frank

以文会友World Corporal Punishemnt Research

| www.corpun.com : Archive : 1976 to 1995 : SG Judicial May 1994 Part II |

| This page is just one of this website's over 2,500 pages of factual documentation and resources on corporal punishment around the world. Have a look at the site's front page or go to the explanatory page, About this website. |

-- THE ARCHIVE --

https://www.corpun.com/awfay9405.htm

SINGAPORE, Judicial CP - May 1994 (Part II)

Asiaweek, Hong Kong, 25 May 1994

Inside Story

Rough Justice

A Caning in Singapore Stirs Up a Fierce Debate About Crime and Punishment

By Alejandro Reyes

At Queenstown Remand Prison, Gurkha guards in smartly angled broad-brimmed hats stand watch in corner towers. The prison's severe walls are painted a gentle cream and powder blue. At the front gate, uniformed children merrily skip off passing school buses and into the compound. Prison officers' families live in flats on the premises. This jail isn't for hardened criminals.

At Queenstown Remand Prison, Gurkha guards in smartly angled broad-brimmed hats stand watch in corner towers. The prison's severe walls are painted a gentle cream and powder blue. At the front gate, uniformed children merrily skip off passing school buses and into the compound. Prison officers' families live in flats on the premises. This jail isn't for hardened criminals.

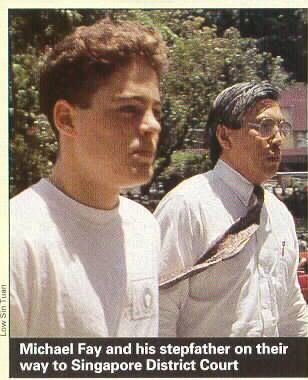

Since March 31, Queenstown has housed Michael Peter Fay, an American teenager who has arguably become Singapore's most famous -- or notorious -- prison inmate. After pleading guilty to vandalism charges, the 18-year-old student was sentenced March 3 to four months in jail, a $2,200 fine -- and six strokes of the cane. That Singapore flogs vandals was not news. But that the island republic would scourge an American was. The story made headlines worldwide, especially after U.S. President Bill Clinton asked the Singapore government to waive the caning, which he called "excessive."

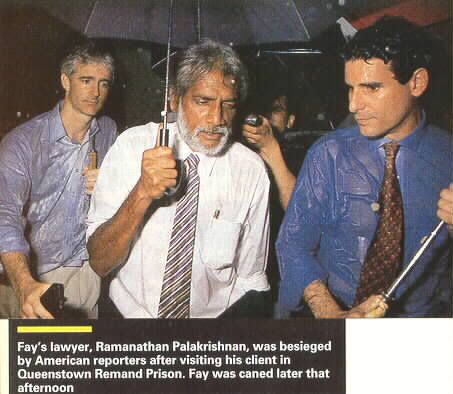

After losing an appeal against his sentence, Fay asked Singapore's President Ong Teng Cheong for clemency. On May 4, the government announced that the Cabinet had recommended to Ong that Fay's caning be reduced to four strokes as a gesture of respect for the American president. Ong sent a letter conveying the decision to Fay's counsel, Ramanathan Palakrishnan. It was not until about noon the next day that the lanky lawyer went to the prison with two assistants to give his client the news. The legal team was inside for more than an hour. "He was happy that the clemency was considered," said Palakrishnan glumly as reporters swarmed around him afterwards. "He thanked his family and asked them to pray for him. He's nervous." Added lawyer Dominic Nagulendran: "He said to thank President Clinton and President Ong. He is resigned to the caning." Would he be caned tomorrow, an American reporter from Fox TV shouted. "I don't think so," replied Palakrishnan. "But it must be as soon as possible."

After losing an appeal against his sentence, Fay asked Singapore's President Ong Teng Cheong for clemency. On May 4, the government announced that the Cabinet had recommended to Ong that Fay's caning be reduced to four strokes as a gesture of respect for the American president. Ong sent a letter conveying the decision to Fay's counsel, Ramanathan Palakrishnan. It was not until about noon the next day that the lanky lawyer went to the prison with two assistants to give his client the news. The legal team was inside for more than an hour. "He was happy that the clemency was considered," said Palakrishnan glumly as reporters swarmed around him afterwards. "He thanked his family and asked them to pray for him. He's nervous." Added lawyer Dominic Nagulendran: "He said to thank President Clinton and President Ong. He is resigned to the caning." Would he be caned tomorrow, an American reporter from Fox TV shouted. "I don't think so," replied Palakrishnan. "But it must be as soon as possible."

Indeed it was. Soon after his lawyers left him, Michael Fay was informed that his caning sentence was to be carried out that afternoon. He was one of ten prisoners flogged that day. In the caning room he was stripped naked. He bent over and his arms and legs were fastened to an H-shaped trestle by straps. A protective covering was placed over his kidneys. A prison official, a medical officer and the caner were the only ones present. The caner wound up and, using his full body weight, struck with the 13mm-thick rattan rod, which had been soaked overnight to prevent it from splitting. Each stroke on Fay's exposed buttocks came about half a minute apart. It was over in minutes. After the fourth and final stroke, say Singapore officials, Fay shook hands with his caner and insisted on walking back to his cell unaided. He wanted to act like a man.

The cases of Fay and eight other expatriate teenagers arrested for vandalism stirred up an international row and roused a fierce debate about crime and punishment. Rightly or wrongly, the affair was transformed from a seemingly simple case of a troubled teen into a philosophical argument about values and cultural clashes. And it put the spotlight on the judicial systems in the U.S., where Americans bemoan rising crime and the ineffectiveness of their penal system, and Singapore, where leaders say strict laws and harsh punishments have meant clean streets and peaceful neighborhoods.

The cases of Fay and eight other expatriate teenagers arrested for vandalism stirred up an international row and roused a fierce debate about crime and punishment. Rightly or wrongly, the affair was transformed from a seemingly simple case of a troubled teen into a philosophical argument about values and cultural clashes. And it put the spotlight on the judicial systems in the U.S., where Americans bemoan rising crime and the ineffectiveness of their penal system, and Singapore, where leaders say strict laws and harsh punishments have meant clean streets and peaceful neighborhoods.

The trouble began on Sept. 18, 1993. At about 8 a.m. Judicial Commissioner Amarjeet Singh, husband of nominated MP Kanwaljit Soin, drove his wife's car to the Supreme Court. He didn't notice anything strange. At 10 a.m., however, the judge was informed by police that something was wrong: his car had been sprayed with red paint. Singh drove home at lunchtime. Back on Chatsworth Road, he noticed that his neighbor Ho Tian Yee's car had also been spray-painted. Police later determined that both cars had been vandalized overnight. That afternoon, Singh drove to a shop, where the paint was removed with thinner and the car polished.

Police linked the incident to other cases. The day before, vandals had struck at a multi-story carpark along Cairnhill Road, spray-painting at least six cars. On Sept. 26, a car off Belmont Road was pelted with eggs and its right front door kicked and dented. The hood of Sin Cheng Tee's car, parked in front of his home on Ming Teck Park, was damaged by a brick. And on Oct. 4, vandals threw eggs at two cars parked at Chancery Court and switched their rear license plates.

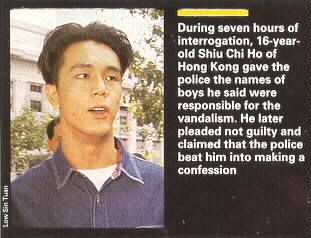

Investigators at Tanglin Police Division Headquarters set out to stop the spree. In the early hours of Oct. 6 they laid an ambush near Chancery Court. The operation paid off. Between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m. police chased down a red Mercedes and arrested 16-year-old International School student Shiu Chi Ho of Hong Kong and a Thai diplomat's son. Shiu had been driving his father's car without a license. The two were taken to the police station. The Thai boy was released once his diplomatic status was determined.

During about seven hours of interrogation, Shiu gave police names of boys he said were responsible for the vandalism. Later that morning, some two dozen police officers went to the Singapore American School and had five students pulled out of their fourth-period class and taken away in three vans. The five arrested included two 15-year-old Malaysians (whose names cannot be reported in Singapore because they were under sixteen at the time), 16-year-old Australian Damien Kirchhoff, and two Americans: Stephen Freehill, then 16, and Michael Fay, 18. Hauled in separately for questioning were American Todd Bailey and a Belgian boy.

The same day, police took Fay to his mother and stepfather's 21st-floor apartment in posh Regency Park. Above the boy's bed hung the American stars & stripes and a Singapore flag. Five other Singapore flags were found in the room, along with two "Not for hire" taxi signs, a "Smoking strictly prohibited" signboard, a "No Exit" sign, and other such items. According to police, the flags and signboards were stolen and had been given to Fay by a Swedish schoolmate who had left Singapore in September.

The same day, police took Fay to his mother and stepfather's 21st-floor apartment in posh Regency Park. Above the boy's bed hung the American stars & stripes and a Singapore flag. Five other Singapore flags were found in the room, along with two "Not for hire" taxi signs, a "Smoking strictly prohibited" signboard, a "No Exit" sign, and other such items. According to police, the flags and signboards were stolen and had been given to Fay by a Swedish schoolmate who had left Singapore in September.

"The suspects may be foreigners from well-to-do families, but they will not get any preferential treatment," said Superintendent Lum Hon Fye when the arrests hit the headlines. Early on, Fay became the center of investigations. He spent nine days in custody, eventually signing a statement of confession. Most of the others were released on bail after two days. Only Fay, Freehill, Shiu, the two Malaysians and Kirchhoff were later charged. Kirchhoff left the country with his family, forfeiting his $1,280 bail.

Fay's mother, Randy Chan, recalls the day her son was arrested: "I returned home that day finding out that they had been in our apartment and had totally ransacked Michael's room." A former airline reservations agent, Chan divorced George Fay when their son was eight. She later married Marco Chan, a Chinese American. The couple moved to Singapore in 1991 when Mr. Chan was named to head Federal Express's regional operations. Michael, who had been living with his father and stepmother, joined his mother the following year.

Mrs. Chan wasn't able to see her son until the second day of his detention. On arrest in Singapore, suspects are not guaranteed immediate access to an attorney. Fay's family would later say that Michael was beaten and coerced into confessing to a long list of offenses. In the U.S., George Fay released details of a nine-page letter he says his son wrote, describing his interrogation. A police officer "asked me if I wanted to get slapped and I told him I did not," the boy is said to have written. "He slapped me real hard on the face. Then I started to cry in fear of what was going to happen next."

Some of the other boys also alleged that they had been roughed up. During his trial, Shiu testified that police hit him with a bat to force him into confessing. There were claims too that one of the Malaysian boys suffered a ruptured eardrum. The U.S. Embassy took up Fay's alleged abuse with Singapore authorities. After an internal police investigation and a medical examination of Fay, says the Home Affairs Ministry, no evidence of physical coercion was found. Shiu's allegations were similarly denied. The Malaysian's case is still under investigation. Sources say his parents have refrained from pursuing the complaint.

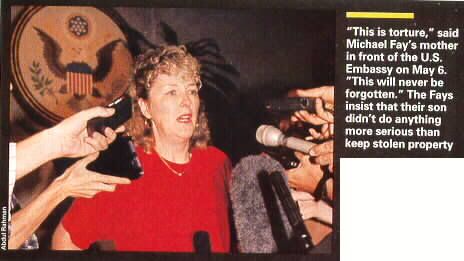

Fay and one of the Malaysians, rather than go on trial jointly with Shiu, decided to plead guilty and plea bargain. The Malaysian was eventually sentenced in juvenile court to two months in a boys' home. Fay had faced a total of 53 charges, mainly vandalism. He and his friends were alleged to have damaged eighteen vehicles over a period of ten days. He pleaded guilty to two vandalism charges, two counts of mischief and one charge of possessing stolen property. Randy Chan now regrets that decision. "I didn't think the lesson to teach a child is to run away from a problem," she says. "I thought we would be treated fairly." She acknowledges that her son did something wrong by taking the signs. But they did not expect a jail term, much less caning.

The Vandalism Act of 1966 was originally conceived as a legal weapon to combat the spread of mainly political graffiti common during the heady days of Singapore's struggle for independence. Enacted a year after the republic left the Malaysian Federation, the law explicitly mandates between three and eight strokes of the cane for each count, though a provision allows first offenders to escape caning "if the writing, drawing, mark or inscription is done with pencil, crayon, chalk or other delible substances and not with paint, tar or other indelible substances."

The issue of indelibility was central to the judge's decision to order Fay caned. Paint was undeniably used to vandalize the cars in question. But the red stains were easily removed using solvents. One of the vandalized vehicles had been restored and polished for under $100. Palakrishnan argued that the fact the paint was easily and cheaply removed should have saved his client from the mandatory thrashing. It didn't. For Judge F.G. Remedios, paint was paint.

The issue of indelibility was central to the judge's decision to order Fay caned. Paint was undeniably used to vandalize the cars in question. But the red stains were easily removed using solvents. One of the vandalized vehicles had been restored and polished for under $100. Palakrishnan argued that the fact the paint was easily and cheaply removed should have saved his client from the mandatory thrashing. It didn't. For Judge F.G. Remedios, paint was paint.

Shiu and his lawyers chose not to plea bargain but to plead not guilty, arguing that the Hong Kong boy's confession was forced out of him and that he had alibis for the nights in question. On April 21, Remedios sentenced Shiu to eight months in prison and twelve strokes on four vandalism charges and a fine for various driving offenses. The teenager and his family decided not to appeal. Theoretically prosecutors can still bring more of the 40 or so remaining charges against the now-17-year-old student, who was taken to Queenstown on May 6, the day after Fay's caning. He is seeking presidential clemency, while the Hong Kong and British governments have asked that his caning be set aside on humanitarian grounds.

Shiu and Fay are part of Singapore's expat teenage set who live with their parents in luxury flats and attend expensive international schools. Like their Singaporean counterparts, they dress in casual designer outfits and hang around Orchard Road shopping centers. The night is for partying at trendy clubs such as Zouk, a popular warehouse-turned-disco.

Shiu's parents are Singapore permanent residents who both work for Singapore Broadcasting Corp. His mother, TV actress Fong Shui Fan, advised her son to confront his problems and not to hide. He continued to go to school after his arrest. Dashing father Chung On, better known in Hong Kong as actor Jiang Long, testified at his son's trial to provide an alibi. The judge didn't believe him. Said Chung On, who heads SBC's Chinese drama department, after his son's conviction: "No matter what the punishment, my son will never admit guilt. I have a court in my heart and my son is innocent."

While Michael Fay lived in expat luxury, his was not a charmed life. His parents' divorce affected him. The boy was diagnosed as suffering from Attention Deficit Disorder. A recently identified neurological disorder, its symptoms include behavioral or learning problems. It is linked to a child's perceived lack of attention. Fay's father admits to driving his son hard. George Fay is the son of Jewish immigrants who survived Nazi death camps -- his mother Magdalena in Auschwitz, his father Steven in Serbia. In 1960 they arrived in the U.S., changing their name from Fekepe. George, who was 13 when his family emigrated, worked as a delivery boy in his parents' dry-cleaning shop in New York. He eventually earned degrees in chemical engineering and moved to St. Louis, where he met and then married Randy, his neighbor. Michael was born in 1975.

Before coming to Singapore, Michael had been in boarding school near Pittsburgh and had lived most of the time with George, stepmother Jan and half-brother Geoffrey. In 1991, George moved to Kettering, Ohio, where he became CEO of a sealant and adhesives company. Mrs. Chan and her new husband moved to Singapore. Michael's parents later decided that their son should live with his mother.

"He's a very active, typical American teenager, very fun-loving, very well-liked, has got hundreds of friends, and is very outgoing," says Mrs. Chan of her son. Michael took to the life of an expat kid in the Lion City. He played baseball, his favorite sport, as well as American football and some tennis. He became a certified diver. He liked Singapore so much that in 1993, rather than return to the U.S. during school holiday, he chose to remain, taking a job as a waiter at the Hard Rock Café. But sources in the American community tell of a problem kid, a known troublemaker, someone "people turned to whenever something bad happened."

The afternoon he was sentenced, Michael Fay immediately went into hospital and was treated for depression. Meanwhile, outside the Subordinate Courts, the first salvo in what was to become a diplomatic row was launched. Responding to reporters' questions, U.S. chargé d'affaires Ralph Boyce said: "We see a large discrepancy between the offense and the punishment. The cars were not permanently damaged; the paint was removed with thinner. Caning leaves permanent scars. In addition, the accused is a teenager and this is his first offense."

By evening, the Singapore government had its reply: "Unlike some other societies which may tolerate acts of vandalism, Singapore has its own standards of social order as reflected in our laws. It is because of our tough laws against anti-social crimes that we are able to keep Singapore orderly and relatively crime-free." The statement noted that in the past five years, fourteen young men aged 18 to 21, twelve of whom were Singaporean, had been sentenced to caning for vandalism. Fay's arrest and sentencing shook the American community in Singapore. Schools advised parents to warn their children not to get into trouble. The American Chamber of Commerce said "We simply do not understand how the government can condone the permanent scarring of any 18-year-old boy -- American or Singaporean -- by caning for such an offense." Two dozen American senators signed a letter to Ong on Fay's behalf.

By evening, the Singapore government had its reply: "Unlike some other societies which may tolerate acts of vandalism, Singapore has its own standards of social order as reflected in our laws. It is because of our tough laws against anti-social crimes that we are able to keep Singapore orderly and relatively crime-free." The statement noted that in the past five years, fourteen young men aged 18 to 21, twelve of whom were Singaporean, had been sentenced to caning for vandalism. Fay's arrest and sentencing shook the American community in Singapore. Schools advised parents to warn their children not to get into trouble. The American Chamber of Commerce said "We simply do not understand how the government can condone the permanent scarring of any 18-year-old boy -- American or Singaporean -- by caning for such an offense." Two dozen American senators signed a letter to Ong on Fay's behalf.

But according to a string of polls, Fay's caning sentence struck a chord in the U.S. Many Americans fed up with rising crime in their cities actually supported the tough punishment. Singapore's embassy in Washington said that the mail it had received was overwhelmingly approving of the tough sentence. And a radio call-in survey in Fay's hometown of Dayton, Ohio, was strongly pro-caning.

It wasn't long before Singapore patriarch Lee Kuan Yew weighed in. He reckoned the whole affair revealed America's moral decay. "The U.S. government, the U.S. Senate and the U.S. media took the opportunity to ridicule us, saying the sentence was too severe," he said in a television interview. "[The U.S.] does not restrain or punish individuals, forgiving them for whatever they have done. That's why the whole country is in chaos: drugs, violence, unemployment and homelessness. The American society is the richest and most prosperous in the world but it is hardly safe and peaceful."

The debate over caning put a spotlight on Singapore's legal system. Lee and the city-state's other leaders are committed to harsh punishments. Preventive detention laws allow authorities to lock up suspected criminals without trial. While caning is mandatory in cases of vandalism, rape and weapons offenses, it is also prescribed for immigration violations such as overstaying visas and hiring of illegal workers. The death penalty is automatic for drug trafficking and firing a weapon while committing a crime. At dawn on May 13, six Malaysians were hanged for drug trafficking, bringing to seventeen the number executed for such offenses so far this year, ten more than the total number of prisoners executed in all of 1993.

Most Singaporeans accept their brand of rough justice. Older folk readily speak of the way things were in the 1950s and 1960s when secret societies and gangs operated freely. Singapore has succeeded in keeping crime low. Since 1988, government statistics show there has been a steady decline in the crime rate from 223 per 10,000 residents to 175 per 10,000 last year. Authorities are quick to credit their tough laws and harsh penalties for much of that.

But the issue is more complex. Canada, whose legal system and philosophy more closely resemble the British and American models, enjoys low crime rates in stark contrast to its neighbor to the south. Hong Kong did away with caning in 1990 and yet its crime rates are comparable to Singapore's. And despite the strict laws and harsh penalties, Singapore has seen a rise in juvenile delinquency, drug abuse and white-collar crime.

Of course Singapore is not the only country to use corporal punishment. At least sixteen countries, including Malaysia, Pakistan and Brunei, mandate caning or flogging as punishment for criminal offenses. But it was the Singapore case that brought out the differences between the legal philosophies that underpin many Asian countries and the U.S. Some have gone so far as to describe the incongruousness as a clash of civilizations.

"If there is a single fundamental difference between the Western and Asian world view, it is the dichotomy between individual freedom and collective welfare," said Singapore businessman and former journalist Ho Kwon Ping in an address to lawyers on May 5, the day Fay was caned. "The Western cliché that it would be better for a guilty person to go free than to convict an innocent person is testimony to the importance of the individual. But an Asian perspective may well be that it is better that an innocent person be convicted if the common welfare is protected than for a guilty person to be free to inflict further harm on the community."

There is a basic difference too in the way the law treats a suspect. "In Britain and in America, they keep very strongly to the presumption of innocence," says Walter Woon, associate professor of law at the National University of Singapore and a nominated MP. "The prosecution must prove that you are guilty. And even if the judge may feel that you are guilty, he cannot convict you unless the prosecution has proven it. So in some cases it becomes a game between the defense and the prosecuting counsel. We would rather convict even if it doesn't accord with the purist's traditions of the presumption of innocence."

Singapore's legal system may be based on English common law, but it has developed its own legal traditions and philosophy since independence. The recent severance of all appeals to the Privy Council in London is part of that process. In fundamental ways, Singapore has departed from its British legal roots. The city-state eliminated jury trials years ago -- the authorities regard them as error-prone. Acquittals can be appealed and are sometimes overturned. And judges have increased sentences on review. Recently an acquittal was overturned and a bus driver was sentenced to death for murder based only on circumstantial evidence. "Toughness is considered a virtue here," says Woon. "The system is stacked against criminals. The theory is that a person shouldn't get off on fancy argument."

Woon opposes caning to punish non-violent offenses. But he is not an admirer of the American system. Last year, Woon and his family were robbed at gunpoint at a bus stop near Disneyworld in Orlando, Florida. The experience shook him. America's legal system, he argues, "has gone completely berserk. They're so mesmerized by the rights of the individual that they forget that other people have rights too. There's all this focus on the perpetrator and his rights, and they forget the fellow is a criminal." Fay is no more than that, Woon says. "His mother and father have no sense of shame. Do they not feel any shame for not having brought him up properly to respect other people's property? Instead they consider themselves victims."

Yet harsh punishments alone are clearly not the salvation of Singapore society. The predominantly Chinese city-state also has a cohesive value system that emphasizes such Confucian virtues as respect for authority, "No matter how harsh your punishments, you're not going to get an orderly society unless the culture is in favor of order," says Woon. "In Britain and America, they seem to have lost the feeling that people are responsible for their own behavior. Here, there is still a sense of personal responsibility. If you do something against the law, you bring shame not only to yourself but to your family."

That "sense of shame," Woon reckons, is more powerful than draconian laws. "Loosening up won't mean there will be chaos," he says. "But the law must be seen to work. The punishment is not the main thing. It's the enforcement of the law. The law has to be enforced effectively and fairly." Woon believes there is room for improvement in Singapore. Opposed to mandatory sentences, he supports giving judges more discretion in determining punishment. And he is critical of the government's decision to reduce Fay's sentence precisely because it was, he says, unfair. "If you have friends in high places that means you get a reduction. One law for Americans and one law for other people is totally unsatisfactory."

Fay, who turns 19 on May 30, is expected to be released from prison on June 21. He and his family will return to the U.S., where he will no doubt make the talk show rounds and reap the monetary benefits of America's fascination with the criminal. Book and movie contracts may take the sting out of his ordeal.

The boy's condition remains in question. His father and American lawyer Theodore Simon say that Michael had to stand throughout a 45-minute meeting with American diplomat John Coe some 24 hours after his caning. Singapore officials say that the teenager sat and was in good spirits. A prisoner released after the caning claims to have seen Fay sleeping on his back. "He's just counting the [remaining] 35 days," said Mrs. Chan as she left Queenstown Remand Prison on May 17 following her first visit to her son since he was caned.

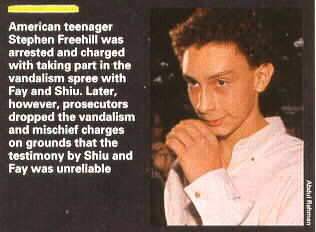

In court last week, Stephen Freehill pleaded guilty to one charge of retaining $13 worth of stolen property. Prosecutors said that because the reliability of testimony from Shiu and Fay was now in doubt, the three charges of vandalism and two counts of mischief against the 17-year-old student had to be dropped. Freehill was alleged to have been one of the accomplices of Fay and Shiu in last year's vandalism spree. With his mother and elder sister looking on, the rail-thin boy was fined $512. His lawyer says the family will remain in Singapore.

In court last week, Stephen Freehill pleaded guilty to one charge of retaining $13 worth of stolen property. Prosecutors said that because the reliability of testimony from Shiu and Fay was now in doubt, the three charges of vandalism and two counts of mischief against the 17-year-old student had to be dropped. Freehill was alleged to have been one of the accomplices of Fay and Shiu in last year's vandalism spree. With his mother and elder sister looking on, the rail-thin boy was fined $512. His lawyer says the family will remain in Singapore.

Washington meanwhile has tapped Singapore lightly on the wrist. Clinton called the caning "a mistake," while the State Department summoned Ambassador S.R. Nathan. Trade negotiator Mickey Kantor indicated that the U.S. would oppose Singapore's bid to host the first World Trade Organization meeting in 1996. But neither side is spoiling for a fight.

What the Fay case revealed is perhaps nothing more than that Singapore is basically a conservative society and America a liberal one. The affair, reckons Woon, "was purely and simply an argument about crime and punishment that could and is taking place within America itself." It's not so much a clash of civilizations, says Woon, as "a clash between a conservative society willing to punish when punishment is called for and a liberal society where people -- or at least the liberal establishment -- are apologetic about punishing criminals. Within the United States, there will be conservative groups who share with us the same beliefs in hard work, thrift, personal responsibility and the value of the family. It's the old Protestant work ethic. It just doesn't seem to percolate upwards."

Michael Fay's mother may not agree with that evaluation. "What this has taught me about my country," said Mrs. Chan, "is how we take everything for granted. We have problems, but we have our freedoms." In Israel last week, Lee Kuan Yew had a different moral: "You know that if you come to Singapore, your life, limb and properties will be quite safe."

Michael Fay's mother may not agree with that evaluation. "What this has taught me about my country," said Mrs. Chan, "is how we take everything for granted. We have problems, but we have our freedoms." In Israel last week, Lee Kuan Yew had a different moral: "You know that if you come to Singapore, your life, limb and properties will be quite safe."

Alejandro Reyes is an Asiaweek Correspondent based in Singapore. He was educated in the United States.

See also:

See also:

More press coverage of the Michael Fay affair: March 1994 -- April 1994 -- May 1994 -- June 1994

Comprehensive illustrated factual article: Judicial caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei

Table of offences for which caning may be ordered in Singapore

External links to other documents on aspects of Singapore's JCP regime: Web links: Judicial CP

THE ARCHIVE index

THE ARCHIVE index

Video clips

Video clips

Picture index

Picture index

About this website

About this website

Country files: Corporal punishment in Singapore

Country files: Corporal punishment in Singapore

www.corpun.com Main menu page

Text and pictures copyright © Asiaweek

This presentation copyright © C. Farrell