Most recession predictions were based on the reasonable assumption that the U.S. Federal Reserve would do whatever was necessary to bring inflation down to the central bank’s 2% target level. During the Fed’s great war on inflation that began in 1979, Fed Chair Paul Volcker was asked if the tight money policies would cause a recession. He answered immediately, “Yes, and the sooner the better.”

In another conversation in 1980, Volcker said that he wouldn’t be satisfied “until the last buzz saw is silenced” — a reference to the devastating effects of higher interest rates on the construction of homes, factories and office buildings.

In 2022, with the rate of inflation threatening to reach double-digit levels, as had been the case in 1979, Fed watchers naturally assumed that the Fed would again jack up interest rates high enough to cause a recession large enough to crush inflation. To their surprise, the Fed engineered a soft landing, bringing down the rate of inflation without causing a recession.

Read: Inflation is ‘far from dead’: Why one large asset manager doubts U.S. can hit 2%

Hanke’s reasoning was more dogmatic, focusing on the U.S. money supply rather than interest rates. He has long held that the quantity theory of money provides a tight linkage between money and inflation. So if, for example, helicopters were to fly around the country dropping money from the sky, thereby doubling the money supply, prices would also double, and life would proceed otherwise undisturbed.

There are several problems with this simplistic model. One is that it assumes that velocity — the ratio of gross domestic product to the money supply —is constant. If this ratio were 5, for example, then, on average, each dollar would be used five times a year to purchase domestically produced goods and services. There is no reason why this ratio should be 5 or any other particular number, especially since money is used to purchase many things that are not included in GDP, including intermediate goods, imports, stocks and other financial assets, along with real estate and other existing real assets.

A second problem is that there is no clearly best way to measure money. Along with many other monetarists, Hanke favors M2, a measurement that includes cash, a variety of bank deposits and retail money-market funds. The idea is that M2 measures readily available funds that people can spend if they want to. The elephant in the room is that many purchases are made with credit cards and consumer and business loans. There is no good way to measure the extent to which these constrain spending.

Nonetheless, Hanke has often relied on the quantity theory of money to argue that there is a tight one-for-one link between M2 and inflation. For example, in 2023 he wrote that “velocity and real output growth are very close to being constant, and … the money supply growth rate and inflation have a near one-to-one relationship.”

That conclusion is demonstrably wrong, but my concern here is with Hanke’s August 2022 prediction of a “whopper of a recession” in 2023 based on a slowing of M2 growth.

We Make The Markets Make Sense

Monetarists love to point accusatory fingers at the Fed, but the U.S. central bank does not directly control monetary aggregates like M2. The Fed uses open-market operations to control the monetary base — currency outside banks plus bank reserves. M2 and other monetary aggregates are determined endogenously by public decisions about how to allocate their wealth among things that are or are not included in M2.

Another complicating factor is that the U.S. dollar is the official currency in several countries, is an unofficial medium of exchange in many others, and is widely held by central banks as foreign-exchange reserves. Almost half of all U.S. currency is now held outside of the United States.

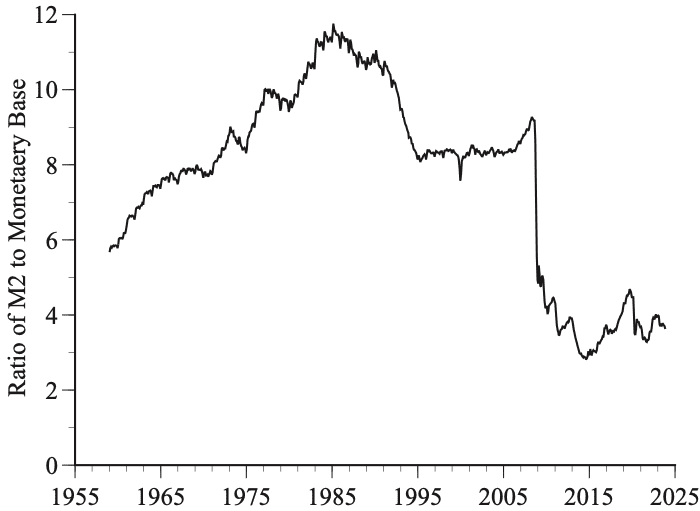

The bottom line is that there is no persuasive reason why M2 should be tightly linked to the monetary base. In practice, it isn’t. This figure of the ratio of M2 to the monetary base shows how loose the connection is. The precipitous drop in the ratio of M2 to the monetary base in 2008 was due to the Fed pumping up the monetary base to keep the Great Recession from turning into the second Great Depression while M2 barely budged. It is deeply misleading to call M2 the money supply, as if this were controlled by the Fed.

These various considerations do not mean that the Fed is impotent. Central bankers can certainly shrivel liquidity and jack up interest rates in order to cause a recession whenever they feel it is in our best interests to be unemployed. What these considerations do mean is that it is foolish to think that there is a tight link between M2 and either inflation or output, and that it is hazardous to make predictions based on wiggles and jiggles in M2.

Gary N. Smith, Fletcher Jones professor of economics at Pomona College, is the author of dozens of research articles and 17 books including, most recently, “The Power of Modern Value Investing: Beyond Indexing, Algos, and Alpha,” co-authored with Margaret Smith (Palgrave Macmillan, 2023).