波比医生的分享

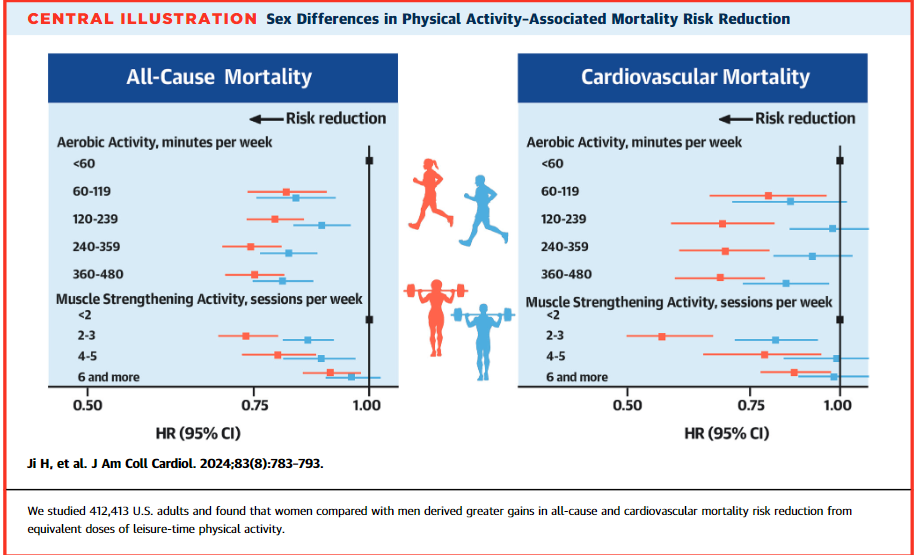

健康&健美的探索和体验分享--Although both sexes achieved a peak survival benefit at 300 min/week aerobic excercise, women derived a 24% mortality reduction vs. men who derived an 18% mortality reduction

--In a Taiwanese cohort studyof 199,265 male and 216,910 female individuals, designed to identify the minimum amount of exercise needed to reduce all-cause mortality, both sexes derived a similar 14% risk reduction in association with as little as 15 minutes of moderate intensity activity per day or 90 min/wk.

--When exercise dose is larger than the above, women derive more benefit.

--It has long been known that male in-dividuals have measurably greater exercise capacitythan female individuals across all ages. This maybe in part due to attributes including on average proportionately larger hearts, wider lung airways, greater lung diffusion capacity, and larger muscle fibers in male compared with female individuals. In particular, men have 38% more lean body mass compared with women.

--Accordingly, although female individuals have generally lower muscle strength at baseline, when both male and female individuals undergo strength training, female individuals experience greater relative improvements in strength, which is a stronger predictor of mortality than muscle mass.

-- Furthermore, sexual dimorphism at the level of muscle fiber type and muscle fiber metabolic, contractile, and dynamic function may also contribute to sex differential responses to the same dose of PA. For example, male individuals have a greater proportion of type II glycolytic muscle fibers ( fast-twitch muscle fibers), whereas female individuals have a greater proportion of type I oxidative fibers (耐力).

--These differences could contribute to not only the known greater female sensitivity to disuse atrophy but also, conversely, the greater female sensitivity to PA observed in our study.

--We did note an age-interaction such that the female benefit appeared to be attenuated in older compared with younger age. Notably, in age-stratified analyses, sex differences were most pronounced for middle-aged adults (ie, ages 40 to 59 years) and this finding aligns with the wealth of prior evidence indicating that relative differences in cardiovascular risk factor burden in middle age are highly impactful on not just later but overall life-long risks for adverse outcome.

ref: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.12.019