风萧萧_Frank

以文会友如果中国统治世界,中国秩序将取代美国成为世界领导者

https://claremontreviewofbooks.com/if-china-ran-the-world/

作者:大卫·P·戈德曼

书评 长期博弈:中国取代美国秩序的大战略 The Long Game: China's Grand Strategy to Displace American Order”

伊丽莎白·库伯勒-罗斯认为,否认是悲伤的第一阶段,它是美国对中国崛起反应的特征。 拉什·多西在《长期博弈》中对中国全球战略的描述是一股可喜的冷空气。 他不止一次指出,中国的实力取决于其经济规模比美国大 25%(按相对价格调整)。 它对运输和通信技术的掌控使其能够“锁定与亚洲国家”以及其他国家的关系。

多西现任国家安全委员会中国事务主任。 在此之前,他在布鲁金斯学会指导“中国倡议”,为拜登政府印太地区政策负责人库尔特·坎贝尔提供建议。 多西在华盛顿的地位确保了这本书本身值得一读的广泛读者。 通过对中国政府和半官方文件的广泛研究,他提炼出了他认为是中国的“大战略”,即用中国的设计取代美国的战后世界秩序。

多西寻求一种替代方案,以取代“那些主张适得其反的对抗策略或妥协性大讨价还价策略的人,这两种策略分别忽视了美国国内的不利因素和中国的战略野心。” 他认为,“这两项努力都得到了政策辩论中广泛反对的部分的支持,最终都源于对华盛顿影响一个强大主权国家政治的能力的一系列类似的紧张和理想主义假设。”

因此,“颠覆中国政府的努力尤其危险”,成功的可能性比“产生全面对抗,从而将竞争从秩序竞争转变为根本性生存竞争”更不可能成功。 在这一点上我非常同意多西的观点。 自邓小平经济改革以来的四十年里,实际人均消费增长了一个数量级,中国人民对之前的不稳定记忆犹新。

** **

多西对权力感兴趣,而不是故作姿态。 他只顺便提到了一次中国的维吾尔人,人权问题在他的故事中扮演着次要角色。 他的主题是他所说的中国计划“塑造二十一世纪,就像美国塑造二十世纪一样”。 他通过美国的镜子看到了这一点。 与“分析冷战期间美国对苏联‘遏制战略’的理论和实践”的研究不同,本书力图分析冷战后中国对美国“位移战略”的理论和实践。 ”

他写道,中国的长期计划“依赖于军事、经济和政治基础”。 突出的军事组成部分是“一支能够执行两栖作战、制海和远距离蓝水任务的海军”。 关键的经济要素包括基础设施支出、“强制性经济治国手段”以及对西方国家技术优势的追求。 在政治领域,中国寻求“以强化其叙事的方式塑造全球信息流”。

多西最擅长学术政治学的奥秘,解析国际机构的字母汤。 他似乎认为联合国是中国的主要目标:“北京抓住了美国的疏忽,努力将其官员安排在联合国十五个专门机构中的四个的最高领导职位上。”

相比之下,他对技术和金融前沿的肤浅了解是这本书的主要弱点。 多西对中国的雄心可能意味着什么的想法过于笼统,无法明确区分中国未来可能想要拥有的东西和国家存在的理由。 他正确地说,“中国秩序”将意味着“取代美国成为世界领导国家”。 在这个新的体制中,“北京将在全球治理和国际机构中发挥领导作用,以牺牲自由主义为代价推进专制规范,并分裂美国在欧洲和亚洲的联盟。”

** **

这很好,但这对台湾意味着什么? 多西没有解释为什么或以何种方式,台湾可能成为北京的宣战理由。 他提出了一个令人信服的理由,即“华盛顿自愿终止对台湾承诺的决定将令美国在该地区的盟友感到震惊”,他们会开始怀疑美国对他们的承诺。 多西暗示,中国希望从台湾得到“地缘战略优势”。

但北京方面并不这么看。 中国不是一个民族国家,而是一个拥有七种主要语言和三百种小语种的帝国,其中

大约十分之一的公民能说流利的普通话。 每个中国王朝的生存恐惧在于,一个叛乱省份将为其他省份开创先例,导致种族和地理上的分裂,就像中国悲惨的过去经常发生的那样。 习近平在2014年亚太经合组织峰会上对奥巴马总统说:“中国是一块土地,也是一个人民。 有时人口增加百分之十,有时减少百分之十。 但中国的土地是神圣不可侵犯的,我们将不择手段地保卫它。”

中国坚持对台湾拥有主权,并不是因为该岛具有战略效用,也不是因为它想压制其民主制度,而是因为中国领土的完整是中国国家的生存问题。 改变现状的唯一选择是一场没有人会赢的战争。 但为了维持现状,美国既不能表现出会诱使中国吞并台湾的软弱,也不能表现出可能让北京认为它正在密谋将一个主权台湾国家与大陆分离的实力。

** **

美军所有涉及大陆攻击台湾的战争游戏都以美国的失败而告终。 中国正在建设10万名准备入侵该岛的海军陆战队和机械化步兵、50多艘潜艇以及强大的陆对海导弹能力,这种能力可能会摧毁大多数在中国海岸附近活动的美国水面舰艇。 正如中国官方英文报纸《环球时报》的编辑于 2021 年 7 月 28 日所写:

美国海军在水上力量方面的优势肯定会持续一段时间。 中国不仅要赶上美国,还要加强陆基导弹力量,在战争中能够打击南海的美国大型战舰。 我们可以大规模扩充这支力量,如果美国在南海挑起军事对抗,其所有大型舰艇都会同时成为陆基导弹的目标。

奥巴马政府前国防部副部长米歇尔·弗卢努瓦(Michèle Flournoy)去年在《外交事务》中指出,要威慑中国,美国必须拥有“可信地威胁击沉中国在南海的所有军舰、潜艇和商船的能力”。 72小时内出海。” 然而,与这种力量相对应的是,中国有可靠的能力更快地消灭美国在南海及其附近的军事设施,从而威慑美国的军事举措和反应。

令人怀疑的是,台湾能否通过常规手段抵御中国的攻击,而使用核武器将使美国城市面临中国报复的风险。 非军事风险可能更有可能抑制中国:如果武力吞并台湾使中国成为全球贱民,西方将承担切断中国与世界经济联系的巨大成本。 中国的经济将会崩溃,共产党的权力也会随之崩溃。

** **

多西意识到,中国对大战略的理解与美国有所不同,因此他大大削弱了自己对大战略的定义。 他承认,中国“可能缺乏拥有数万名士兵的联盟网络和基地,并且回避代价高昂的干预。 当其军队在印太以外地区挑战美国仍面临困难时,它更有可能选择军民两用设施、轮换访问和更轻的足迹——至少目前如此。” 这让我想起一个古老的犹太笑话:“什么是绿色的,挂在墙上,还吹着口哨?” 答案是“鲱鱼”。 但鲱鱼是绿色的吗? 好吧,你可以把它漆成绿色。 但它挂在墙上吗? 嗯,你可以把它挂在墙上。 但它会吹口哨吗? 好吧,它不吹口哨。

尽管如此,令多西感到困扰的是,中国只有一个海外基地(在吉布提,主要是为了反海盗行动,保护中国航运而建立的)。 毕竟,如果没有远征军和其他形式的全球兵力投送,战略就不可能宏伟。 他表示,中国拥有斯里兰卡和格陵兰岛的港口、在格陵兰岛建设机场以及租赁马尔代夫的一个小岛,“表明中国对全球设施的兴趣与日俱增”。 他指出,自 2016 年以来,中国海军陆战队的人数已从 10,000 人扩大到 30,000 人。(相比之下,美国现役海军陆战队有 180,000 人。)

最后,多西承认,中国投射力量的努力仍然低调。 “中国或许能够在印太地区以外开展行动,而无需精确复制美国复杂且成本高昂的全球足迹。” 事实上,多西对中国军事规划的令人信服的描述支持了这样的结论:中国更关注其边界而不是全球。 例如,他认为“反水面战是中国潜艇的首要任务,这……表明重点关注美国舰艇,尤其是航母。” 反过来

“中国海军学说也确认了将潜艇作为拒止工具而不是护航或海上控制资产的重点。”

但所有这些都不足以构成美国冷战立场意义上的中国“大战略”,而这正是作者承诺揭露的。 除了中国随时准备恐吓台湾的军事资产外,其“远征”部队在保护危机地区中国公民方面的作用也有限,例如 2011 年在利比亚和 2015 年也门。 美国无力将军事力量投射到远离其直接陆地和海上边界的地方。

** **

事实上,中国经常因美国退出全球力量投射而显得措手不及。 北京对美国从阿富汗仓促撤军表示真正的不安,阿富汗与中国和巴基斯坦的边界都存在漏洞。 美国人离开后塔利班上台,加剧了中国发生圣战恐怖主义的风险。

伊朗与中国的和解还带来了另一组问题:中国从沙特阿拉伯进口的石油比任何其他国家都多,而且什叶派取代沙特君主制的野心也令人不安。 北京与维吾尔分裂主义的潜在盟友土耳其保持着亲密的朋友和敌人的关系,通过贿赂和威胁相结合的方式劝阻土耳其不要支持它曾经所谓的“东突厥斯坦”。 过去十年我曾多次暗示中东可能会出现“中国治下的和平”。 然而,中国对于为这个动荡且不可预测的地区承担责任并没有表现出多少兴趣。

多西在总结中指出,中国全球野心的另一个方面是其自称的目标,即通过“对市场可能会回避的基础科学研究进行巨额投资”来主导第四次工业革命。 他接受美国国家科学基金会的估计,即中国用于研发的支出占 GDP 的比例明显高于美国。在最先进的技术方面,这种差距尤其巨大:“中国的支出至少比美国多十倍。” 在量子计算领域。”

他还正确地指出,中国的工业深度使其在技术推广方面比美国具有巨大优势。 《长博弈》援引中国人民大学教授金灿荣的话说,中国更有机会引领第四次工业革命,因为美国“有一个重大问题,就是其工业基础空心化”。 如果没有中国工厂,美国“无法将技术转化为市场可接受的产品”。 灿荣认为,中国数量众多的工程师、逆向工程能力以及工厂在全球技术中的中心地位是“中国在长期产业竞争中的真正优势”。

** **

多西对中国金融雄心的讨论不太令人信服,因为他对主题的把握不稳。 他写道:“中国官员长期以来一直担心美国主导的数字货币有可能提振美元体系,因此他们一直在争夺先发优势。” 对此,“美国应该认真研究,然后考虑推出一种数字货币,既能保留其金融优势,又能实现(中国官员)所担心的世界——一种补充并锚定于世界的数字货币。” 美元体系。”

美元储备体系与之前的英镑储备体系一样,通过将贸易支付与资本市场挂钩,允许美国在经常账户上产生巨额赤字。 外国人拥有 7 万亿美元的美国国债,但更重要的是,他们在离岸账户中保留了 16 万亿美元的美元余额(根据国际清算银行的报告),主要作为国际交易的营运资金。 中国既没有能力也没有意愿“取代”美国,这需要开放其资本市场并使其受到全球资本流动变幻莫测的影响。 因此,中国的数字货币电子支付并不是针对美国金融霸权的灵丹妙药,而是一种便利,就像全球的PayPal一样。

对美国金融霸权的真正威胁不是来自数字货币本身,而是来自所谓的智能物流和“物联网”的融合。 中国正在竞相引领运输和仓储领域的一场革命,使交易对手能够追踪全球生产和运输各个阶段的所有货物,从而使全球供应链变得透明。 这将大大削弱银行系统作为中介的作用,并减少贸易所需的营运资金。 中国领先的电信设备公司华为在其网站上解释道:

通过在所有部门之间透明地共享信息并可视化物料流,

系统更好地协调人、车、货、库。 同时实现与外部风险数据的实时互联,实现替代方案的预警和智能提醒。 在配送过程中,大数据和人工智能对货物存储计划和最佳运输路线进行智能计算,以提高配送效率和优化资产利用。

生产成本为几美分的芯片将被嵌入到每一种交易产品中,并与服务器实时通信,将它们引导至自动化仓库、无人驾驶卡车、数字控制港口,并最终到达最终用户。 人工智能将把货物引导至最便宜、最快的运输方式,并让买家找到最便宜的价格。 服务器和货物之间的5G通信将验证贸易中数万亿件物品的生产、运输和存储状态。 国际贸易交易所需的营运资金将减少。

** **

正如摩根士丹利经济学家在今年早些时候的一份报告中指出的那样,央行数字货币(CBDC)将掏空银行系统的存款基础:

商业银行将面临脱媒风险。 一旦推出 CBDC 账户,消费者将能够将银行存款转移到那里,但须遵守央行施加的限制。 此外,CBDC的技术基础设施将使新的非银行实体更容易进入支付领域并加速向数字支付的过渡。

银行体系的存款基础将受到侵蚀,16万亿美元的离岸美元存款将逐渐消失。 但这 16 万亿美元相当于向美国提供的无息贷款,因为银行将收益投资于美国政府或私人债务工具。 在大数据和人工智能在物流中的应用中,美国可能会损失数十万亿美元的铸币税,最初是君主通过将金条变成硬币而赚取的溢价的术语。 16 世纪的西班牙君主国花费巨额资金开采、运输和保护金条,以弥补其赤字。 荷兰和英国的中央银行以更高效的资本利用方式取代了这一系统。 智慧物流和数字金融的出现将带来资本效率的又一次质的飞跃。

多西认为美国数字货币能够解决问题的观点是错误的。 困难在于,中国在部署 5G 网络以及建设 5G 支持的制造和物流技术方面比美国领先几年。 此外,与第四次工业革命相关的技术可能会给中国带来在世界大片地区一定程度的影响力,这在现有工业组织的框架内是难以想象的。 发展中国家的数十亿人生活在全球经济的边缘,在自给自足的土地上工作,从事小商业,几乎无法获得信息、教育、医疗保健和社会服务。 廉价的移动宽带正在将他们与世界市场连接起来,将他们融入华为所谓的电信、电子商务、电子金融、远程医疗和智慧农业的“生态系统”中。 我在《你将被同化》(2020)中将其称为世界的“中国化”。 在过去的35年里,中国从基层瓦解了传统社会,使6亿人口城市化,它相信在未来十年内可以将数十亿人融入其虚拟帝国。 问题在于技术的细节,而多西似乎不了解这些细节。

** **

那么,美国应该做什么呢? 美国要求与中国供应链脱钩的压力一直没有效果。 “中国欧盟商会发现,只有约 11% 的会员考虑在 2020 年迁出中国,”多西写道。 同样,“中国美国商会会长指出,该组织的大多数成员并不打算离开中国。”

然而,《漫长的游戏》中缺少对中美之间半导体战争的描述。 正如哈佛大学的格雷厄姆·艾利森 (Graham Allison) 在 2020 年 6 月 11 日发表在《国家利益》上的文章中指出的那样,特朗普政府抵制中国收购高端半导体知识产权的行为让人回想起富兰克林·罗斯福 (Franklin Roosevelt) 1941 年对日本的石油抵制。 中国以大规模投资和“全国努力”来回应,以建立芯片生产的独立性,并且在此期间似乎取得了相当大的成功。 特朗普的芯片制裁是迄今为止美国阻止中国引领第四次工业革命的最激进的尝试,但似乎失败了,甚至可能适得其反。 我们应该做什么,下一步应该做什么?

多西在这里沉默了:“半导体”一词没有出现在他的索引中。 他希望美国在资源方面投入更多资金

实施培育高新技术产业的产业政策,大力培育高水平STEM教育。 这很好,但令人失望的是,新政府负责对华政策的一位官员拒绝考虑拜登政府延续的上届政府的政策。

多西还建议美国应该发明区域拒止武器,以实现“一种‘无人海’,任何行动者都无法成功控制第一岛链的水域或岛屿或发起两栖作战。” 他补充说,我们应该帮助台湾、日本、越南、菲律宾、印度尼西亚、马来西亚和印度也这样做。 此外,如果中国试图建立海外基地,美国就应该“破坏中国建立海外基地的昂贵努力”。 当然,还要对抗中国在联合国的影响力,多西认为这很重要。

这些建议无可厚非,但却是通用的。 多西从中国收集了大量有用的材料,并将其与西方的分析进行了比较。 这对得起这本书的价格。 但可以说,他只见树木不见森林:他太少关注中国政策的独特之处,正是这些独特之处使中国成为了如此强大的竞争对手。 在这里寻找有关拜登政府未来对华立场线索的读者将会感到失望。

《长期博弈:中国取代美国秩序的大战略》编者注

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-long-game-chinas-grand-strategy-to-displace-american-order/

编者节选《长期博弈:中国取代美国秩序的大战略》

2021 年 8 月 2 日

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-long-game-chinas-grand-strategy-to-displace-american-order/

作者:前布鲁金斯学会研究员拉什·多西

拉什·多西(Rush Doshi),前布鲁金斯学会专家, 是布鲁金斯学会中国战略项目主任,也是布鲁金斯学会外交政策研究员。 他还是耶鲁大学法学院蔡保罗中国中心的研究员,也是首届威尔逊中国研究员的成员。 他的研究重点是中国大战略以及印太安全问题。 他目前在拜登政府任职。

这一介绍性章节总结了本书的论点。 它解释了中美之间的竞争是关于地区和全球秩序的,概述了中国主导的秩序可能是什么样子,探讨了大战略为何重要以及如何研究它,并讨论了关于中国是否有大战略的不同观点。 它认为,中国试图通过在军事、政治和经济层面实施的三个连续的“取代战略”,将美国从地区和全球秩序中取代。 第一个战略旨在削弱美国的地区秩序,第二个战略旨在建立中国的地区秩序,而第三个战略——扩张战略——现在寻求在全球范围内实现这两项战略。 引言解释说,中国战略的转变受到改变其对美国实力看法的重大事件的深刻影响。

介绍

那是 1872 年,李鸿章写作正值历史性的剧变时期。 李是一位清朝将军和官员,一生大部分时间致力于改革垂死的帝国,经常被拿来与同时代的奥托·冯·俾斯麦相比较。奥托·冯·俾斯麦是德国统一和国家权力的缔造者,据说李一直保留着他的肖像以获取灵感。1

与俾斯麦一样,李克强也拥有军事经验,他将这些经验转化为相当大的影响力,包括对外交和军事政策的影响。 他在镇压长达十四年的太平天国运动中发挥了重要作用,这是整个十九世纪最血腥的冲突,见证了一个千年基督教国家从清朝权力日益真空的情况下崛起,发动了一场夺去了数千万人生命的内战。 。 这次镇压叛乱的行动使李先生对西方武器和技术有了欣赏,对欧洲和日本掠夺的恐惧,对中国自强和现代化的承诺,以及至关重要的影响力和声望,为此采取了一些行动。

在一份主张加大对中国造船业投资的备忘录中,李鸿章写下了几代人重复的一句话:中国正在经历“三千年未有之大变局”。

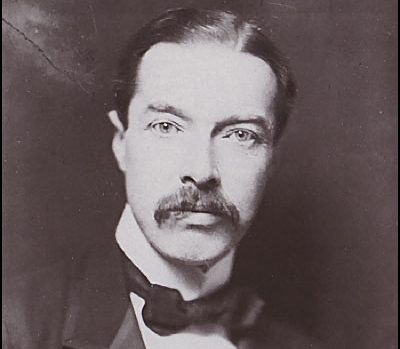

左:李鸿章,也罗马化为李鸿章,1896 年。资料来源:Alice E. Neve Little,李鸿章:他的一生和时代(伦敦:Cassell & Company,1903 年)。

因此,正是在 1872 年,李在他的众多信件中,反思了他在自己的生活中看到的突破性的地缘政治和技术变革,这些变革对清朝的生存构成了威胁。 在一份主张加大对中国造船业投资的备忘录中,他写下了几代人重复的一句话:中国正在经历“三千年未见的巨变”2。

对于许多中国民族主义者来说,这句著名的、笼统的言论提醒我们国家自己所遭受的耻辱。 李最终未能实现中国的现代化,输给了日本,并与东京签署了令人尴尬的《马关条约》。 但对许多人来说,李的路线既具有先见之明,又准确无误——中国的衰落是清朝未能正视三千多年来未曾出现过的变革性地缘政治和技术力量的结果,这些力量改变了国际力量平衡并迎来了新的发展。 在中国的“世纪耻辱”中。 这是李的一切努力都无法扭转的趋势。

文件照片:2019年5月14日,中国国家主席习近平在中国北京人民大会堂外出席希腊总统普罗科皮斯·帕夫洛普洛斯的欢迎仪式。路透社/Jason Lee/文件照片

如果说李克强的路线标志着中国屈辱的顶峰,那么习近平的路线则标志着中国复兴的契机。 如果说李克强的言论引发了悲剧,那么习近平的言论则引发了机遇。

右:习近平,自 2013 年起担任中华人民共和国国家主席。资料来源:路透社

现在,中国领导人习近平重新调整了李克强的路线,开启了中国后冷战大战略的新阶段。 2017年以来,习近平在多次重要的外交政策讲话中宣称,世界正处于“百年未有之大变局”。 如果说李克强的路线标志着中国屈辱的顶峰,那么习近平的路线则标志着中国复兴的契机。 如果说李克强的言论引发了悲剧,那么习近平的言论则引发了机遇。 但两者都抓住了一些基本问题:由于前所未有的地缘政治和技术转变,世界秩序再次受到威胁,这需要战略调整。

对习近平来说,这些转变的根源在于中国不断增长的实力以及它所认为的西方明显的自我毁灭。 2016年6月23日,英国公投决定脱离欧盟。 然后,再多一点

三个月后,民粹主义浪潮将唐纳德·特朗普推上美国总统宝座。 从对美国实力和威胁看法的变化高度敏感的中国角度来看,这两起事件令人震惊。 北京认为,世界上最强大的民主国家正在退出它们在国外帮助建立的国际秩序,并在国内努力进行自我治理。 西方随后在 2020 年对冠状病毒大流行的反应,以及 2021 年极端分子袭击美国国会大厦,都强化了一种感觉:正如习近平在这些事件发生后不久所说的那样,“时间和势头都站在我们这边”。3 领导层和外交政策精英宣称,一个“历史机遇期”已经出现,可以将中国的战略重点从亚洲扩大到更广阔的全球及其治理体系。

我们现在正处于未来发展的初期——中国不仅像许多大国那样寻求地区影响力,而且正如埃文·奥斯诺斯所说,“它正准备塑造二十一世纪,就像美国一样。” 塑造了第二十个。”4影响力的竞争将是一场全球性的竞争,北京有充分的理由相信,未来十年可能会决定结果。

中国的雄心是什么?有实现这些雄心的宏伟战略吗? 如果确实如此,那么该战略是什么,它是由什么形成的,以及美国应该采取什么措施?

当我们进入这一新的激烈竞争阶段时,我们缺乏关键基础问题的答案。 中国的雄心是什么?有实现这些雄心的宏伟战略吗? 如果确实如此,那么该战略是什么,它是由什么形成的,以及美国应该采取什么措施? 这些是美国决策者应对本世纪最大的地缘政治挑战的基本问题,尤其是因为了解对手的战略是应对对手的第一步。 然而,随着大国紧张局势加剧,人们对答案尚未达成共识。

本书试图给出一个答案。 本书的论点和结构部分受到美国大战略冷战研究的启发。 5 这些著作分析了冷战期间美国对苏联“遏制战略”的理论和实践,而本书力求 分析冷战后中国对美“位移战略”的理论与实践。

为此,本书利用了中国共产党文件的原始数据库——回忆录、传记和高级官员的日常记录——是过去几年从台湾和香港的图书馆、书店精心收集并数字化的。 中国电子商务网站(见附录)。 许多文件将读者带入中国共产党的大门后面,带他们进入其高层外交政策机构和会议,并向读者介绍负责制定和实施外交政策的广大中国政治领导人、将军和外交官。 中国的大战略。 虽然没有一份主文件包含了中国的全部大战略,但其概要可以在大量文本中找到。 在其中,党使用代表关键问题的内部共识的等级声明来指导国家的航船,并且这些声明可以跨时间追溯。 其中最重要的是路线,然后是方针,最后是政策等。 理解它们有时不仅需要精通中文,还需要精通“辩证统一”和“历史唯物主义”等看似深奥而古老的意识形态概念。

简要论证

该书认为,冷战以来美中竞争的核心一直是地区秩序,现在是全球秩序。 它重点关注中国等新兴大国在无需战争的情况下取代美国等老牌霸主所采用的战略。 霸权在地区和全球秩序中的地位源于三种广泛的“控制形式”,这些形式用于规范其他国家的行为:强制能力(强制遵守)、共识性诱因(激励它)和合法性(正确指挥) 它)。 对于崛起中的国家来说,和平取代霸权的行动包括通常按顺序实施的两大战略。 第一个战略是削弱霸权对这些形式的控制的行使,特别是对新兴国家的控制; 毕竟,如果任何崛起的国家仍受霸权摆布,那么它就无法取代霸权。 第二是建立对他人的控制形式; 事实上,任何崛起国家如果不能通过胁迫性威胁、协商一致的诱导或合法性来获得其他国家的尊重,就不可能成为霸权。 除非崛起的大国首先削弱霸权,否则建立秩序的努力很可能是徒劳的,而且很容易遭到反对。 直到一个崛起的国家成功地进行

尽管在其本土地区经历了一定程度的削弱和建设,但它仍然太容易受到霸权国家的影响,无法自信地转向第三种战略,即全球扩张,即在全球层面寻求削弱和建设,以取代霸权国家的国际领导地位。 这些在地区和全球层面上的战略共同为中国共产党的民族主义精英提供了一条粗略的上升途径,他们寻求使中国恢复其应有的地位,并扭转西方压倒性全球影响力的历史偏差。

这是中国遵循的模板,在回顾中国的取代战略时,该书认为,从一种战略转向下一种战略是由塑造中国大战略的最重要变量的急剧不连续性引发的:对美国实力的看法 和威胁。 中国的第一个流离失所战略(1989-2008)是悄悄削弱美国对中国的影响力,特别是在亚洲,它是在天安门广场、海湾战争和苏联解体的三重创伤导致北京大幅增强其对中国的看法之后出现的。 美国的威胁。 中国的第二个驱逐战略(2008年至2016年)旨在为亚洲地区霸权奠定基础,该战略是在全球金融危机导致北京看到美国实力减弱并有勇气采取更加自信的做法后启动的。 现在,随着英国脱欧、特朗普总统当选和新冠病毒大流行等“百年未有之大变局”,中国正在启动第三项驱逐战略,即在全球范围内扩大削弱和建设力度,以取代美国 全球领导者。 在最后几章中,本书利用对中国战略的见解来制定一项不对称的美国大战略作为回应——该战略借鉴了中国自己的书——并寻求在不进行美元对美元竞争的情况下挑战中国的地区和全球野心。 船对船,或贷款对贷款。

国外秩序往往是国内秩序的反映,而中国的秩序建设相对于美国的秩序建设显然是不自由的。

书中还阐述了如果中国能够在2049年中华人民共和国成立一百周年之际实现“民族复兴”的目标,中国的秩序会是什么样子。在地区层面,中国已经占到了一半以上 亚洲GDP的一半和亚洲军费开支的一半,这正在使该地区失去平衡并走向中国的势力范围。 一项完全实现的中国命令最终可能包括美国从日本和韩国撤军、结束美国的地区联盟、美国海军从西太平洋有效撤军、尊重中国的地区邻国、与台湾统一以及通过决议 东海和南海的领土争端。 中国的秩序可能比现在的秩序更具强制力,以主要有利于有联系的精英的方式达成共识,甚至不惜牺牲投票公众的利益,并且主要对那些直接奖励的少数人来说被认为是合法的。 中国将以损害自由价值观的方式部署这一秩序,使独裁之风在该地区刮得更猛。 国外秩序往往是国内秩序的反映,而中国的秩序建设相对于美国的秩序建设显然是不自由的。

在全球层面,中国秩序将涉及抓住“百年未有之大变局”的机遇,取代美国成为世界领导国家。 这需要通过削弱支持美国全球秩序的控制形式,同时加强支持中国替代方案的控制形式,成功管理来自“伟大变革”(华盛顿不愿优雅地接受衰落)带来的主要风险。 这一秩序将跨越亚洲的“超级影响力区”以及大片发展中国家的“部分霸权”,并可能逐渐扩大到涵盖世界工业化中心——一些中国通俗作家用毛泽东的革命指导来描述这一愿景 “农村包围城市”。 6 更有权威的消息人士对这种做法的表述不那么笼统,认为中国的秩序将植根于中国的“一带一路”倡议及其共同命运共同体,而前者是中国的“一带一路”倡议及其共同命运共同体的基础。 特别是创建强制能力、共识诱导和合法性网络。 7

曾经仅限于亚洲的“控制权之争”现在已经影响到全球秩序及其未来。 如果说通往霸权的道路有两条——区域一条和全球一条——那么中国现在正在两条道路上追求。

习近平的讲话中已经可以看出实现这一全球秩序的一些战略。 在政治上,北京将在全球治理和国际机构中发挥领导作用,分裂西方联盟,并在全球范围内推行独裁规范。

以自由主义者为代价。 从经济上看,这将削弱支撑美国霸权的金融优势,并夺取从人工智能到量子计算的“第四次工业革命”的制高点,美国将沦为“去工业化的、英语版的拉丁美洲共和国”。 ,专门从事大宗商品、房地产、旅游业,也许还有跨国逃税。”8在军事上,中国人民解放军(PLA)将派出一支世界级的军队,在世界各地设有基地,可以捍卫中国在大多数地区甚至在某些地区的利益。 新领域,如太空、两极和深海。 这一愿景的各个方面在高层演讲中显而易见,这一事实有力地证明了中国的野心不仅限于台湾或主宰印度-太平洋地区。 曾经仅限于亚洲的“控制权之争”现在已经影响到全球秩序及其未来。 如果说通往霸权的道路有两条——区域一条和全球一条——那么中国现在正在两条道路上追求。

对中国可能出现的秩序的一瞥也许令人震惊,但这并不奇怪。 十多年前,一位富有远见的政治家李光耀(Lee Kuan Yew)——一位建立了现代新加坡并亲自认识中国最高领导人的政治家——被一位采访者问到:“中国领导人是否认真地想要取代美国成为亚洲乃至世界第一强国?” ?” 他斩钉截铁地回答说是。 “当然。 为什么不?” 他开始说道,“他们通过经济奇迹改变了一个贫穷的社会,成为现在世界第二大经济体——步入正轨……” 。 。 成为世界第一大经济体。” 他接着说,中国拥有“4000年悠久的文化和13亿人口,拥有庞大的人才库可供借鉴。 他们怎么能不渴望成为亚洲第一,乃至世界第一呢?” 他指出,中国“50年前正以难以想象的速度增长,这是一场无人预料到的巨大转变”,“每个中国人都希望有一个强大、富裕的中国,一个像美国、欧洲和日本一样繁荣、先进、技术实力雄厚的国家”。 ”。 他以一个关键的见解结束了他的回答:“这种重新唤醒的命运感是一种压倒性的力量。 。 。 。 中国希望成为中国并被接受为中国,而不是作为西方的荣誉成员。” 他指出,中国可能希望与美国“共享这个世纪”,也许是“平起平坐”,但肯定不是作为附属国。 9

为什么大战略很重要

切实了解中国的意图和战略的必要性从未如此迫切。 中国现在提出了美国从未面临过的挑战。 一个多世纪以来,美国的任何对手或对手联盟都没有达到美国 GDP 的 60%。 无论是第一次世界大战期间的威廉德国、第二次世界大战期间日本帝国和纳粹德国的联合力量,还是经济实力鼎盛时期的苏联,都没有跨过这个门槛。 10 然而,这是中国的一个里程碑 早在 2014 年,中国就已悄然达到这一目标。如果调整商品相对价格,中国经济规模已经比美国经济高出 25%。11 显然,中国是美国面临的最重要的竞争对手 华盛顿处理超级大国地位的方式将决定下个世纪的进程。

大战略之所以“伟大”,不仅在于战略目标的规模,还在于通过协调不同的“手段”来实现战略目标。

至少在华盛顿,不太清楚的是中国是否有一个宏伟战略以及它可能是什么。 本书将大战略定义为一个国家如何通过军事、经济和政治等多种治国手段有目的、协调和实施来实现其战略目标的理论。 大战略之所以“伟大”,不仅在于战略目标的规模,还在于通过协调不同的“手段”来实现战略目标。 这种协调是罕见的,因此大多数大国都没有宏伟的战略。

然而,当国家确实制定了宏伟战略时,它们就可以重塑世界历史。 纳粹德国实行的大战略是利用经济手段制约邻国,利用军事建设来恐吓对手,利用政治结盟来包围对手,这使得它在国内生产总值还不到一倍的情况下,在相当长的时间内超越了大国竞争对手。 -第三是他们的。 冷战期间,华盛顿奉行一项宏伟战略,有时利用军事力量遏制苏联的侵略,利用经济援助削弱共产主义的影响力,利用政治制度将自由国家团结在一起——在不引发美苏战争的情况下限制苏联的影响力。 中国如何同样整合其治国手段来追求总体地区和全球目标,仍然是一个引起了大量猜测的领域,但很少有严格的研究,尽管它

造成巨大的后果。 大战略中涉及的协调和长期规划使国家能够超越其实力; 因为中国已经是一个重量级国家,如果它有一个连贯的计划,将其 14 万亿美元的经济与其蓝水海军和在世界各地不断上升的政治影响力相协调——而美国要么错过了它,要么误解了它——二十世纪九十年代的进程 第一世纪可能会以不利于美国及其长期以来所倡导的自由主义价值观的方式展开。

华盛顿迟来地接受了这一现实,其结果是对其中国政策进行了一代人以来最重要的重新评估。 然而,在这次重新评估中,对于中国想要什么以及走向何方存在广泛分歧。 一些人认为北京有全球野心; 其他人则认为其重点主要是区域性的。 一些人声称它有一个协调一致的 100 年计划; 其他人则认为这是机会主义的并且容易出错。 一些人将北京称为大胆的修正主义国家; 其他人则将其视为当前秩序的清醒利益相关者。 有人说北京希望美国退出亚洲;有人说北京希望美国退出亚洲。 和其他人认为,它容忍美国扮演温和的角色。 分析人士越来越认同这样一种观点,即中国最近的自信是中国国家主席习近平个性的产物——这是一个错误的观点,忽视了中共长期以来的共识,而中国的行为实际上植根于此。 事实上,当代辩论在与中国大战略相关的许多基本问题上仍然存在分歧,甚至在主要共识领域也不准确,这一事实令人不安,特别是因为每个问题都具有截然不同的政策含义。

悬而未决的争论

本书卷入了一场关于中国战略的尚未解决的争论,争论分为“怀疑论者”和“相信者”。 怀疑论者尚未相信中国拥有在地区或全球范围内取代美国的宏伟战略; 相比之下,信徒并没有真正尝试说服。

怀疑论者是一个范围广泛、知识渊博的群体。 “中国尚未制定真正的‘大战略’,”一位成员指出,“问题在于它是否愿意这样做。”12其他人则认为,中国的目标是“不成熟的”,北京缺乏“ 13 北京大学国际关系学院前院长王缉思教授等中国作家也属于持怀疑态度的阵营。 他指出:“我们绞尽脑汁也想不出能够涵盖我们国家利益所有方面的战略。”14

其他怀疑论者认为,中国的目标有限,认为中国不希望在地区或全球范围内取代美国,仍然主要关注发展和国内稳定。 一位经验丰富的白宫官员尚未相信“习近平希望将美国赶出亚洲并摧毁美国的地区联盟。”15其他著名学者更有力地表达了这一点:“[一个]严重扭曲的概念是现在所有的 -一种过于普遍的假设,即中国寻求将美国逐出亚洲并征服该地区。 事实上,没有确凿的证据证明中国的此类目标。”16

与这些怀疑论者相反的是信徒。 该团体相信中国拥有在地区和全球范围内取代美国的宏伟战略,但尚未提出说服怀疑论者的工作。 在政府内部,一些高级情报官员——包括前国家情报总监丹·科茨——公开表示,“中国从根本上寻求取代美国成为世界主导力量”,但没有(或者可能无法)进一步阐述 ,他们也没有暗示这一目标伴随着具体的战略。 17

在政府之外,只有少数最近的著作试图详细阐述这一点。 最著名的是五角大楼官员迈克尔·皮尔斯伯里 (Michael Pillsbury) 的畅销书《一百年马拉松》,尽管该书有些夸大地指出,中国自 1949 年以来就制定了一个关于全球霸权的秘密宏伟计划,并且在关键地方严重依赖个人权威和轶事。 18 许多其他书籍 得出类似的结论,而且大多是正确的,但它们比严格的经验更直观,如果采用社会科学方法和更丰富的证据基础,它们可能更具说服力。 19 一些关于中国大战略的著作采取了更广阔的视角,强调遥远的未来 过去或未来,但因此他们对从后冷战时代到现在的关键时期(即美中竞争的核心)投入的时间较少。 20最后,一些著作将更加实证的方法与谨慎而精确的论点结合起来。 中国当代大战略. 这些作品构成了本书方法的基础。21

这本书借鉴了许多其他人的研究成果,也希望在关键方面脱颖而出。 其中包括独特的社交

l-定义和研究大战略的科学方法; 大量很少被引用或以前无法访问的中文文献; 对中国军事、政治和经济行为中的关键难题进行系统研究; 并仔细研究影响战略调整的变量。 总而言之,希望本书能够以独特的方法系统而严谨地揭示中国的大战略,为新兴中国的争论做出贡献。

揭示大战略

从竞争对手的不同行为中解读其大战略的挑战并不是什么新鲜事。 第一次世界大战前的几年里,英国外交官艾尔·克罗撰写了一份长达 20,000 字的重要《英国与法国和德国关系现状备忘录》,试图解释崛起中的德国的广泛行为。 22 克罗 他是英德关系的敏锐观察者,对这一主题充满热情和视角,这源于他自己的传统。 克罗出生于莱比锡,在柏林和杜塞尔多夫接受教育,他有一半德国血统,说着带有德国口音的英语,21 岁时加入英国外交部。 第一次世界大战期间,他的英国和德国家族实际上处于交战状态——他的英国侄子在海上丧生,而他的德国表弟则升任德国海军参谋长。

英国外交官艾尔·克罗(Eyre Crowe,1864-1925)。 日期未知。 作者不详。 资料来源:维基共享资源

克罗在他的企业框架中指出,“选择必须介于……之间。 。 。 两个假设”——每一个假设都类似于当今怀疑论者和信徒对中国大战略的立场。

左:英国外交官艾尔·克罗(Eyre Crowe,1864-1925 年)。 日期未知。 作者不详。 资料来源:维基共享资源

克罗于 1907 年撰写了他的备忘录,试图系统地分析德国各种截然不同、复杂且看似不协调的对外行为,以确定柏林是否有一个贯穿其中的“宏伟设计”,并向他的上级报告它的内容。 可能。 克罗在他的企业框架中指出,为了“制定并接受一种适合德国外交政策所有已确定事实的理论,“选择必须介于……之间。 。 。 两个假设”——每一个都类似于当今怀疑论者和信徒对中国大战略的立场。 23

克罗的第一个假设是,德国没有大战略,只有他所说的“模糊、混乱和不切实际的政治才能”。 克罗写道,按照这种观点,“德国可能并不真正知道她的目的是什么,她所有的短途旅行和警报,她所有的秘密阴谋都无助于稳定地制定一个精心构思和不懈遵循的计划”。 ”24 如今,这一论点反映了怀疑论者的观点,他们声称中国的官僚政治、派系内讧、经济优先事项和民族主义本能反应都合谋阻碍北京制定或执行总体战略。 24

克罗的第二个假设是,德国行为的重要因素是通过一项宏伟战略协调在一起的,“有意识地旨在首先在欧洲,最终在世界上建立德国霸权。”26克罗最终支持了一个更为谨慎的版本。 他的结论是,德国的战略“深深植根于两国的相对地位”,而柏林对永远服从伦敦的前景感到不满。26这一论点反映了中国大战略信徒的立场。 这也类似于本书的论点:中国在地区和全球层面上采取了各种战略来取代美国,这些战略从根本上来说是由其与华盛顿的相对地位驱动的。

美国官员并没有忽视克罗备忘录探讨的问题与我们今天正在努力解决的问题惊人相似的事实。 亨利·基辛格在《论中国》中引用了这句话。 美国前驻华大使马克斯·博卡斯 (Max Baucus) 经常向中方对话者提到这份备忘录,以此作为询问中国战略的一种迂回方式。 28

克罗的备忘录有着复杂的遗产,当代人们对他对德国的看法是否正确存在分歧。 尽管如此,克罗设定的任务在今天仍然至关重要且同样困难,特别是因为中国是信息收集的“硬目标”。 人们可能希望通过一种基于社会科学的更严格和可证伪的方法来改进克罗的方法。 正如下一章详细讨论的那样,本书认为,要确定中国大战略的存在、内容和调整,研究者必须找到以下证据:(1)权威文本中的大战略概念; (二)国家安全机构的大战略能力; (3)国家行为中的大战略行为。 如果没有这样的方法,任何分析都更有可能

成为“感知和误解”中自然偏见的受害者,这种偏见经常在对其他权力的评估中反复出现。 29

章节摘要

本书认为,自冷战结束以来,中国奉行一项宏伟战略,首先在地区层面,现在在全球层面取代美国秩序。

第一章定义了大战略和国际秩序,然后探讨了崛起大国如何通过削弱、建设和扩张战略取代霸权秩序。 它解释了对既定霸权的力量和威胁的看法如何影响崛起大国大战略的选择。

《漫长的游戏:中国取代美国秩序的大战略》一书封面

了解更多 ”

第二章重点讨论中国共产党作为中国大战略的连接性制度组织。 作为一个从晚清爱国主义浪潮中崛起的民族主义机构,共产党现在的目标是到2049年让中国在全球秩序中恢复应有的地位。作为一个具有集权结构、无情的不道德和列宁主义先锋队的列宁主义机构 该党自视为民族主义项目的管理者,拥有协调多种治国手段的“大战略能力”,同时追求国家利益而非地方利益。 总之,党的民族主义取向有助于确定中国大战略的目标,而列宁主义则为实现这些目标提供了工具。 现在,随着中国的崛起,冷战期间在苏联秩序中坐立难安的同一个政党不太可能永远容忍在美国秩序中扮演从属角色。 最后,本章将党作为一个研究主题,指出仔细审查党的大量出版物如何能够洞察其宏伟的战略概念。

第一部分从第三章开始,利用中国共产党的文本探讨了冷战后中国大战略的钝化阶段。 它表明,在三件事件发生后,中国从将美国视为对抗苏联的准盟友,转变为将其视为中国最大的威胁和“主要对手”:天安门广场大屠杀、海湾战争、 和苏联的崩溃。 作为回应,北京在党的“隐藏能力、等待时机”的指导方针下启动了钝化战略。 这一战略具有实用性和战术性。 党的领导人明确地将这一指导方针与“国际力量平衡”和“多极化”等措辞中对美国实力的看法联系起来,他们试图通过军事、经济和政治手段悄悄地、不对称地削弱美国在亚洲的实力,每一个手段 这将在本书的后续三章中进行讨论。

第四章讨论了军事层面的钝化。 这表明,这三重奏促使中国从日益注重控制遥远海域的“海上控制”战略转向注重阻止美军穿越、控制或干预中国附近海域的“海上拒止”战略。 这种转变具有挑战性,因此北京宣布将“在某些领域迎头赶上”,并誓言要建造“敌人害怕的任何东西”来实现这一目标——最终推迟购买航空母舰等昂贵且脆弱的船只,转而投资于 更便宜的非对称拒止武器。 北京随后建造了世界上最大的水雷库、世界上第一个反舰弹道导弹和世界上最大的潜艇舰队——所有这些都是为了削弱美国的军事实力。

第五章讨论了政治层面的钝化。 这表明,三连击导致中国扭转了此前反对加入地区机构的立场。 北京担心亚太经济合作组织(APEC)和东南亚国家联盟地区论坛(ARF)等多边组织可能被华盛顿用来建立自由的地区秩序,甚至亚洲北约,因此中国加入这些组织来削弱美国的影响力。 力量。 它阻碍了制度进步,利用制度规则限制美国的行动自由,并希望参与能够安抚警惕的邻国,否则它们可能会加入美国领导的平衡联盟。

第六章考虑了经济层面的钝化。 报告认为,这三重打击暴露了中国对美国市场、资本和技术的依赖——特别是华盛顿在天安门事件后实施的制裁以及威胁取消最惠国贸易地位,这可能严重损害中国经济。 北京寻求的不是与美国脱钩,而是约束美国经济实力的自由裁量权,并努力通过“永久正常贸易关系”,利用亚太经合组织和世界贸易组织的谈判,将最惠国待遇从国会审查中剔除。 )来获取它。

因为党的领导人明确将钝化与对美国实力的评估联系起来,这意味着什么

当这些观念发生变化时,中国的大战略也发生了变化。 本书的第二部分探讨了中国大战略的第二阶段,其重点是建立地区秩序。 这一战略是在邓小平“韬光养晦”指导思想的修改下实施的,改为强调“积极办事”。

第七章探讨了党内文本中的这一建设战略,表明全球金融危机的冲击导致中国认为美国正在衰弱,并鼓励其转向建设战略。 它首先对中国关于“多极化”和“国际力量对比”的论述进行了彻底的审视。 然后它表明,在中国领导人胡锦涛发布的修订后的指导方针“积极有所作为”的支持下,党寻求为秩序奠定基础——强制能力、协商一致和合法性。 这一战略,就像之前的钝化一样,是在多种治国手段(军事、政治和经济)中实施的,每个手段都有一个章节。

第八章重点关注军事层面的建设,讲述全球金融危机如何加速中国军事战略的转变,从单一关注通过海上拒止削弱美国实力转向新关注通过海上控制建立秩序。 中国现在寻求拥有控制遥远岛屿、保卫海域、干预邻国以及提供公共安全物资的能力。 为了实现这些目标,中国需要一种不同的军队结构,但此前中国曾推迟这一结构,因为担心它会受到美国的攻击并令中国的邻国感到不安。 更加自信的北京现在愿意接受这些风险。 中国迅速加大对航空母舰、水面舰艇、两栖作战、海军陆战队和海外基地的投资。

第九章重点讨论政治层面的建设。 它展示了全球金融危机如何导致中国从专注于加入和拖延区域组织的钝化战略转向涉及建立自己的机构的建设战略。 中国牵头成立了亚洲基础设施投资银行(AIIB),并将此前默默无闻的亚洲相互协作与信任措施会议(CICA)提升至制度化水平。 然后,它利用这些机构作为工具,按照它喜欢的方向塑造经济和安全领域的区域秩序,并取得了不同程度的成功。

第10章重点讨论经济层面的建设。 报告认为,全球金融危机帮助北京从针对美国经济影响力的防御性削弱战略转向旨在建设中国自己的强制和协商一致的经济能力的进攻性建设战略。 这一努力的核心是中国的“一带一路”倡议、对邻国大力运用经济治国手段,以及试图获得更大的金融影响力。

北京利用这些削弱和建设战略来限制美国在亚洲的影响力,并为地区霸权奠定基础。 该战略的相对成功是引人注目的,但北京的野心不仅限于印太地区。 当华盛顿再次被视为绊脚石时,中国的大战略发生了变化——这一次是朝着更加全球化的方向发展。 因此,本书的第三部分重点讨论中国的第三个战略:全球扩张,旨在削弱但特别是建立全球秩序,并取代美国的领导地位。

第十一章讨论中国扩张战略的曙光。 它认为,该战略是在另一个三连环之后出现的,这一次包括英国脱欧、唐纳德·特朗普当选以及西方对冠状病毒大流行的最初反应不佳。 在此期间,中国共产党达成了一个矛盾的共识:它的结论是,美国在全球范围内退却,但同时在双边方面却开始意识到中国的挑战。 在北京看来,“百年未有之大变局”正在发生,它们提供了到2049年取代美国成为全球领先国家的机会,而未来十年被认为是实现这一目标最关键的十年。

第十二章讨论中国扩张战略的“方式方法”。 这表明,在政治上,北京将寻求对全球治理和国际机构发挥领导作用,并推进独裁规范。 在经济上,它将削弱支撑美国霸权并抢占“第四次工业革命”制高点的金融优势。 在军事上,解放军将部署一支真正的全球性中国军队,并在世界各地设有海外基地。

第十三章是本书的最后一章,概述了美国对中国取代美国在地区和全球秩序中的野心的回应。 它批评

那些主张采取适得其反的对抗战略或奉行妥协性大交易的人提出这样的说法,这两种策略分别忽视了美国国内的不利因素和中国的战略野心。 相反,本章主张一种不对称竞争战略,即不需要与中国进行美元对美元、船对船或贷款对贷款的匹配。

这种具有成本效益的方法强调否认中国在其本土地区的霸权,并借鉴中国自己的钝化战略的要素,重点以比北京建立霸权的成本更低的方式破坏中国在亚洲和世界范围内的努力。 与此同时,本章认为,美国也应该追求秩序建设,对北京目前寻求削弱的美国全球秩序的基础进行再投资。 这次讨论旨在让政策制定者相信,即使美国面临国内外挑战,它仍然可以确保自身利益并抵制非自由势力范围的扩张——但前提是它认识到击败对手战略的关键是 首先要了解它。

尾注

1.Harold James,《克虏伯:英国传奇企业的历史》(新泽西州普林斯顿:普林斯顿大学出版社,2012 年),51。

2、本备忘录见李鸿章《筹议制造轮船未可裁撤折》,载《李文忠公全集》卷11。 19, 1872, 45. 李鸿章又名李文忠。

3.习近平[习近平],《习近平在学习贯彻党的十九届五中全会精神研讨会开幕式上发表重要讲话》[习近平在省部级主要领导 干部学习贯彻党的十九届五中全会精神专题研讨班开班式上发表重要讲话],新华社,2021年1月11日。

4.埃文·奥斯诺斯,“美国与中国竞争的未来”,《纽约客》,2020 年 1 月 13 日,https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/01/13/the-future-of-americas- 与中国的竞争。

5. 例如,John Lewis Gaddis,《遏制战略:冷战期间美国国家安全政策的批判性评估》(英国牛津:牛津大学出版社,2005 年)。

6.Robert E. Kelly,“中国霸权会是什么样子?”,《外交官》,2014 年 2 月 10 日,https://thediplomat.com/2014/02/what-would-chinese-hegemony-look-like/; Nadège Rolland,“中国对新世界秩序的愿景”(华盛顿特区:国家亚洲研究局,2020 年),https://www.nbr.org/publication/chinas-vision-for-a-new-world -命令/。

7.参见袁鹏,《新冠疫情与百年未有之大变局》,《新冠疫情与百年变局》,《现代国际关系》,第1期。 5(2020 年 6 月):1-6,由国家安全部主要智库负责人撰写。

8.Michael Lind,“中国问题”,Tablet,2020 年 5 月 19 日,https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/china-strategy-trade-lind。

9.格雷厄姆·艾利森和罗伯特·布莱克威尔,“专访:李光耀谈美中关系的未来”,《大西洋月刊》,2013 年 3 月 5 日,https://www.theatlantic.com/china/archive/2013/03/ 采访李光耀谈中美关系的未来/273657/。

10.Andrew F. Krepinevich,“保持平衡:美国欧亚防御战略”(华盛顿特区:战略和预算评估中心,2017 年 1 月 19 日),https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/Preserving_the_Balance_% 2819Jan17%29HANDOUTS.pdf。

11.“GDP,(美元)”,世界银行,2019 年,https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gdp.mktp.cd。

12.Angela Stanzel、Jabin Jacob、Melanie Hart 和 Nadège Rolland,“宏伟设计:中国是否有‘宏伟战略’”(欧洲外交关系委员会,2017 年 10 月 18 日),https://ecfr.eu/publication /grands_designs_does_china_have_a_grand_strategy/#.

13.苏珊·谢克(Susan Shirk),“路线修正:迈向有效和可持续的中国政策”(评论,国家新闻俱乐部,华盛顿特区,2019年2月12日),https://asiasociety.org/center-us-china-relations/ 事件/针对有效和可持续的中国政策的路线修正。

14.引自罗伯特·萨特,《中国外交关系:冷战以来的权力与政策》,第三版。 (拉纳姆,医学博士:Rowman 和 Littlefield,2012),9-10。 另见王缉思,“中国寻求大战略:崛起的大国找到出路”,《外交》90,第 11 期。 2(2011):68-79,https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2011-02-20/chinas-search-grand-strategy。

15.Jeffrey A. Bader,“习近平如何看待世界及其原因”(华盛顿特区:布鲁金斯学会,2016),http://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ xi_jinping_worldview_bader-1.pdf。

16.Michael Swaine,“美国无力妖魔化中国”,《外交政策》,2018 年 6 月 29 日,https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/06/29/the-u-s-cant-afford-to-demonize -中国/。

17.Jamie Tarabay,“中央情报局官员:中国希望取代美国成为世界超级大国”,CNN,2018 年 7 月 21 日,https://www.cnn.com/2018/07/20/politics/china-cold-war- us-superpower-influence/index.html。 丹尼尔·科茨,“年度威胁评估”(证词,2019 年 1 月 29 日),https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/Newsroom/Testimonies/2019-01-29-ATA-Opening-Statement_Final.pdf。

18.阿拉斯泰尔·伊恩·约翰斯顿,“摇摇欲坠的基础:特朗普对华政策的‘智力架构’”,《生存》61期,第1期。 2(2019):189-202,https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2019.1589096; 裘德·布兰切特,“魔鬼在脚注中:读迈克尔·皮尔斯伯里的百年马拉松”(加利福尼亚州拉霍亚:加州大学圣地亚哥分校21世纪中国项目,2018),https://china.ucsd.edu/_files/ 百年马拉松.pdf。

19.乔纳森·沃德,《中国的胜利愿景》(华盛顿特区:阿特拉斯出版和媒体公司,2019); 马丁·雅克,《当中国统治世界:中央王国的崛起和西方世界的终结》(纽约:企鹅出版社,2012 年)。

20.Sulmaan Wasif Khan,《混乱所困扰:从毛泽东到习近平的中国大战略》(马萨诸塞州剑桥:哈佛大学出版社,2018 年); Andrew Scobell、Edmund J. Burke、Cortez A. Cooper III、Sale Lilly、Chad J. R. Ohlandt、Eric Warner、J.D. Williams,中国的大战略趋势、轨迹和长期竞争(加利福尼亚州圣莫尼卡:兰德公司,2020) ,https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2798.html。

21.参见艾弗里·戈德斯坦(Avery Goldstein),《迎接挑战中国的大战略和国际安全》(加利福尼亚州斯坦福:斯坦福大学出版社,2005 年); Aaron L. Friedberg,《霸权之争:中国、美国和亚洲的统治斗争》(纽约:W. W. Norton,2012 年); David Shambaugh,《中国走向全球:部分权力》(英国牛津:牛津大学出版社,2013 年); 阿什利·J·特利斯 (Ashley J. Tellis),“追求全球影响力:中国迈向卓越的漫长征程”,《战略亚洲 2019:中国不断扩大的战略野心》,编辑。 Ashley J. Tellis、Alison Szalwinski 和 Michael Wills(华盛顿特区:国家亚洲研究局,2019 年),3–46,https://www.nbr.org/publication/strategic-asia-2019-chinas-expanding -战略野心/。

22. 欲了解全文以及英国外交部内部对此的回应,请参阅艾尔·克罗 (Eyre Crowe),《英国与法国和德国关系现状备忘录》,载于《英国关于战争起源的文件》,1898 年 –1914 年,编辑。 G. P. Gooch 和 Harold Temperley(伦敦:国王陛下文具办公室,1926 年),397-420。

29.Robert Jervis,《国际政治中的看法和误解》(新泽西州普林斯顿:普林斯顿大学出版社,1976 年)。

关于作者

拉什·多西(Rush Doshi),前布鲁金斯学会专家, 是布鲁金斯学会中国战略项目主任,也是布鲁金斯学会外交政策研究员。 他还是耶鲁大学法学院蔡保罗中国中心的研究员,也是首届威尔逊中国研究员的成员。 他的研究重点是中国大战略以及印太安全问题。 他目前在拜登政府任职。

Editor's Note on The Long Game: China's Grand Strategy to Displace American Order

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-long-game-chinas-grand-strategy-to-displace-american-order/

Editor's Note: The following is an excerpt from

The Long Game: China's Grand Strategy to Displace American Order”

by former Brookings Fellow Rush Doshi. Aug. 2 2021

This introductory chapter summarizes the book’s argument. It explains that U.S.-China competition is over regional and global order, outlines what Chinese-led order might look like, explores why grand strategy matters and how to study it, and discusses competing views of whether China has a grand strategy. It argues that China has sought to displace America from regional and global order through three sequential “strategies of displacement” pursued at the military, political, and economic levels. The first of these strategies sought to blunt American order regionally, the second sought to build Chinese order regionally, and the third — a strategy of expansion — now seeks to do both globally. The introduction explains that shifts in China’s strategy are profoundly shaped by key events that change its perception of American power.

Introduction

It was 1872, and Li Hongzhang was writing at a time of historic upheaval. A Qing Dynasty general and official who dedicated much of his life to reforming a dying empire, Li was often compared to his contemporary Otto von Bismarck, the architect of German unification and national power whose portrait Li was said to keep for inspiration.1

Like Bismarck, Li had military experience that he parlayed into considerable influence, including over foreign and military policy. He had been instrumental in putting down the fourteen-year Taiping rebellion—the bloodiest conflict of the entire nineteenth century—which had seen a millenarian Christian state rise from the growing vacuum of Qing authority to launch a civil war that claimed tens of millions of lives. This campaign against the rebels provided Li with an appreciation for Western weapons and technology, a fear of European and Japanese predations, a commitment to Chinese self-strengthening and modernization—and critically—the influence and prestige to do something about it.

In a memorandum advocating for more investment in Chinese shipbuilding, [Li Hongzhang] penned a line since repeated for generations: China was experiencing “great changes not seen in three thousand years.”

Left: Li Hongzhang, also romanised as Li Hung-chang, in 1896. Source: Alice E. Neve Little, Li Hung-Chang: His Life and Times (London: Cassell & Company, 1903).

And so it was in 1872 that in one of his many correspondences, Li reflected on the groundbreaking geopolitical and technological transformations he had seen in his own life that posed an existential threat to the Qing. In a memorandum advocating for more investment in Chinese shipbuilding, he penned a line since repeated for generations: China was experiencing “great changes not seen in three thousand years.”2

That famous, sweeping statement is to many Chinese nationalists a reminder of the country’s own humiliation. Li ultimately failed to modernize China, lost a war to Japan, and signed the embarrassing Treaty of Shimonoseki with Tokyo. But to many, Li’s line was both prescient and accurate—China’s decline was the product of the Qing Dynasty’s inability to reckon with transformative geopolitical and technological forces that had not been seen for three thousand years, forces which changed the international balance of power and ushered in China’s “Century of Humiliation.” These were trends that all of Li’s striving could not reverse.

If Li’s line marks the highpoint of China’s humiliation, then Xi’s marks an occasion for its rejuvenation. If Li’s evokes tragedy, then Xi’s evokes opportunity.

Right: Xi Jinping, president of the People’s Republic of China since 2013. Source: Reuters

Now, Li’s line has been repurposed by China’s leader Xi Jinping to inaugurate a new phase in China’s post–Cold War grand strategy. Since 2017, Xi has in many of the country’s critical foreign policy addresses declared that the world is in the midst of “great changes unseen in a century” [百年未有之大变局]. If Li’s line marks the highpoint of China’s humiliation, then Xi’s marks an occasion for its rejuvenation. If Li’s evokes tragedy, then Xi’s evokes opportunity. But both capture something essential: the idea that world order is once again at stake because of unprecedented geopolitical and technological shifts, and that this requires strategic adjustment.

For Xi, the origin of these shifts is China’s growing power and what it saw as the West’s apparent self-destruction. On June 23, 2016, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. Then, a little more than three months later, a populist surge catapulted Donald Trump into office as president of the United States. From China’s perspective—which is highly sensitive to changes in its perceptions of American power and threat—these two events were shocking. Beijing believed that the world’s most powerful democracies were withdrawing from the international order they had helped erect abroad and were struggling to govern themselves at home. The West’s subsequent response to the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, and then the storming of the US Capitol by extremists in 2021, reinforced a sense that “time and momentum are on our side,” as Xi Jinping put it shortly after those events.3 China’s leadership and foreign policy elite declared that a “period of historical opportunity” [历史机遇期] had emerged to expand the country’s strategic focus from Asia to the wider globe and its governance systems.

We are now in the early years of what comes next—a China that not only seeks regional influence as so many great powers do, but as Evan Osnos has argued, “that is preparing to shape the twenty-first century, much as the U.S. shaped the twentieth.”4 That competition for influence will be a global one, and Beijing believes with good reason that the next decade will likely determine the outcome.

What are China’s ambitions, and does it have a grand strategy to achieve them? If it does, what is that strategy, what shapes it, and what should the United States do about it?

As we enter this new stretch of acute competition, we lack answers to critical foundational questions. What are China’s ambitions, and does it have a grand strategy to achieve them? If it does, what is that strategy, what shapes it, and what should the United States do about it? These are basic questions for American policymakers grappling with this century’s greatest geopolitical challenge, not least because knowing an opponent’s strategy is the first step to countering it. And yet, as great power tensions flare, there is no consensus on the answers.

This book attempts to provide an answer. In its argument and structure, the book takes its inspiration in part from Cold War studies of US grand strategy.5 Where those works analyzed the theory and practice of US “strategies of containment” toward the Soviet Union during the Cold War, this book seeks to analyze the theory and practice of China’s “strategies of displacement” toward the United States after the Cold War.

To do so, the book makes use of an original database of Chinese Communist Party documents—memoirs, biographies, and daily records of senior officials—painstakingly gathered and then digitized over the last several years from libraries, bookstores in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and Chinese e-commerce sites (see Appendix). Many of the documents take readers behind the closed doors of the Chinese Communist Party, bring them into its high-level foreign policy institutions and meetings, and introduce readers to a wide cast of Chinese political leaders, generals, and diplomats charged with devising and implementing China’s grand strategy. While no one master document contains all of Chinese grand strategy, its outline can be found across a wide corpus of texts. Within them, the Party uses hierarchical statements that represent internal consensus on key issues to guide the ship of state, and these statements can be traced across time. The most important of these is the Party line (路线), then the guideline (方针), and finally the policy (政策), among other terms. Understanding them sometimes requires proficiency not only in Chinese, but also in seemingly impenetrable and archaic ideological concepts like “dialectical unities” and “historical materialism.”

Argument in Brief

The book argues that the core of US-China competition since the Cold War has been over regional and now global order. It focuses on the strategies that rising powers like China use to displace an established hegemon like the United States short of war. A hegemon’s position in regional and global order emerges from three broad “forms of control” that are used to regulate the behavior of other states: coercive capability (to force compliance), consensual inducements (to incentivize it), and legitimacy (to rightfully command it). For rising states, the act of peacefully displacing the hegemon consists of two broad strategies generally pursued in sequence. The first strategy is to blunt the hegemon’s exercise of those forms of control, particularly those extended over the rising state; after all, no rising state can displace the hegemon if it remains at the hegemon’s mercy. The second is to build forms of control over others; indeed, no rising state can become a hegemon if it cannot secure the deference of other states through coercive threats, consensual inducements, or rightful legitimacy. Unless a rising power has first blunted the hegemon, efforts to build order are likely to be futile and easily opposed. And until a rising power has successfully conducted a good degree of blunting and building in its home region, it remains too vulnerable to the hegemon’s influence to confidently turn to a third strategy, global expansion, which pursues both blunting and building at the global level to displace the hegemon from international leadership. Together, these strategies at the regional and then global levels provide a rough means of ascent for the Chinese Communist Party’s nationalist elites, who seek to restore China to its due place and roll back the historical aberration of the West’s overwhelming global influence.

This is a template China has followed, and in its review of China’s strategies of displacement, the book argues that shifts from one strategy to the next have been triggered by sharp discontinuities in the most important variable shaping Chinese grand strategy: its perception of US power and threat. China’s first strategy of displacement (1989–2008) was to quietly blunt American power over China, particularly in Asia, and it emerged after the traumatic trifecta of Tiananmen Square, the Gulf War, and the Soviet collapse led Beijing to sharply increase its perception of US threat. China’s second strategy of displacement (2008–2016) sought to build the foundation for regional hegemony in Asia, and it was launched after the Global Financial Crisis led Beijing to see US power as diminished and emboldened it to take a more confident approach. Now, with the invocation of “great changes unseen in a century” following Brexit, President Trump’s election, and the coronavirus pandemic, China is launching a third strategy of displacement, one that expands its blunting and building efforts worldwide to displace the United States as the global leader. In its final chapters, this book uses insights about China’s strategy to formulate an asymmetric US grand strategy in response—one that takes a page from China’s own book—and would seek to contest China’s regional and global ambitions without competing dollar-for-dollar, ship-for-ship, or loan-for-loan.

Order abroad is often a reflection of order at home, and China’s order-building would be distinctly illiberal relative to US order-building.

The book also illustrates what Chinese order might look like if China is able to achieve its goal of “national rejuvenation” by the centennial of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 2049. At the regional level, China already accounts for more than half of Asian GDP and half of all Asian military spending, which is pushing the region out of balance and toward a Chinese sphere of influence. A fully realized Chinese order might eventually involve the withdrawal of US forces from Japan and Korea, the end of American regional alliances, the effective removal of the US Navy from the Western Pacific, deference from China’s regional neighbors, unification with Taiwan, and the resolution of territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas. Chinese order would likely be more coercive than the present order, consensual in ways that primarily benefit connected elites even at the expense of voting publics, and considered legitimate mostly to those few who it directly rewards. China would deploy this order in ways that damage liberal values, with authoritarian winds blowing stronger across the region. Order abroad is often a reflection of order at home, and China’s order-building would be distinctly illiberal relative to US order-building.

At the global level, Chinese order would involve seizing the opportunities of the “great changes unseen in a century” and displacing the United States as the world’s leading state. This would require successfully managing the principal risk flowing from the “great changes”—Washington’s unwillingness to gracefully accept decline—by weakening the forms of control supporting American global order while strengthening those forms of control supporting a Chinese alternative. That order would span a “zone of super-ordinate influence” in Asia as well as “partial hegemony” in swaths of the developing world that might gradually expand to encompass the world’s industrialized centers—a vision some Chinese popular writers describe using Mao’s revolutionary guidance to “surround the cities from the countryside” [农村包围城市].6 More authoritative sources put this approach in less sweeping terms, suggesting Chinese order would be anchored in China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its Community of Common Destiny, with the former in particular creating networks of coercive capability, consensual inducement, and legitimacy.7

The “struggle for mastery,” once confined to Asia, is now over the global order and its future. If there are two paths to hegemony—a regional one and a global one—China is now pursuing both.

Some of the strategy to achieve this global order is already discernable in Xi’s speeches. Politically, Beijing would project leadership over global governance and international institutions, split Western alliances, and advance autocratic norms at the expense of liberal ones. Economically, it would weaken the financial advantages that underwrite US hegemony and seize the commanding heights of the “fourth industrial revolution” from artificial intelligence to quantum computing, with the United States declining into a “deindustrialized, English-speaking version of a Latin American republic, specializing in commodities, real estate, tourism, and perhaps transnational tax evasion.”8 Militarily, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) would field a world-class force with bases around the world that could defend China’s interests in most regions and even in new domains like space, the poles, and the deep sea. The fact that aspects of this vision are visible in high-level speeches is strong evidence that China’s ambitions are not limited to Taiwan or to dominating the Indo-Pacific. The “struggle for mastery,” once confined to Asia, is now over the global order and its future. If there are two paths to hegemony—a regional one and a global one—China is now pursuing both.

This glimpse at possible Chinese order maybe striking, but it should not be surprising. Over a decade ago, Lee Kuan Yew—the visionary politician who built modern Singapore and personally knew China’s top leaders—was asked by an interviewer, “Are Chinese leaders serious about displacing the United States as the number one power in Asia and in the world?” He answered with an emphatic yes. “Of course. Why not?” he began, “They have transformed a poor society by an economic miracle to become now the second-largest economy in the world—on track . . . to become the world’s largest economy.” China, he continued, boasts “a culture 4,000 years old with 1.3 billion people, with a huge and very talented pool to draw from. How could they not aspire to be number one in Asia, and in time the world?” China was “growing at rates unimaginable 50 years ago, a dramatic transformation no one predicted,” he observed, and “every Chinese wants a strong and rich China, a nation as prosperous, advanced, and technologically competent as America, Europe, and Japan.” He closed his answer with a key insight: “This reawakened sense of destiny is an overpowering force. . . . China wants to be China and accepted as such, not as an honorary member of the West.” China might want to “share this century” with the United States, perhaps as “co-equals,” he noted, but certainly not as subordinates.9

Why Grand Strategy Matters

The need for a grounded understanding of China’s intentions and strategy has never been more urgent. China now poses a challenge unlike any the United States has ever faced. For more than a century, no US adversary or coalition of adversaries has reached 60 percent of US GDP. Neither Wilhelmine Germany during the First World War, the combined might of Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany during the Second World War, nor the Soviet Union at the height of its economic power ever crossed this threshold.10 And yet, this is a milestone that China itself quietly reached as early as 2014. When one adjusts for the relative price of goods, China’s economy is already 25 percent larger than the US economy.11 It is clear, then, that China is the most significant competitor that the United States has faced and that the way Washington handles its emergence to superpower status will shape the course of the next century.

What makes grand strategy “grand” is not simply the size of the strategic objectives but also the fact that disparate “means” are coordinated together to achieve it.

What is less clear, at least in Washington, is whether China has a grand strategy and what it might be. This book defines grand strategy as a state’s theory of how it can achieve its strategic objectives that is intentional, coordinated, and implemented across multiple means of statecraft—military, economic, and political. What makes grand strategy “grand” is not simply the size of the strategic objectives but also the fact that disparate “means” are coordinated together to achieve it. That kind of coordination is rare, and most great powers consequently do not have a grand strategy.

When states do have grand strategies, however, they can reshape world history. Nazi Germany wielded a grand strategy that used economic tools to constrain its neighbors, military buildups to intimidate its rivals, and political alignments to encircle its adversaries—allowing it to outperform its great power competitors for a considerable time even though its GDP was less than one-third theirs. During the Cold War, Washington pursued a grand strategy that at times used military power to deter Soviet aggression, economic aid to curtail communist influence, and political institutions to bind liberal states together—limiting Soviet influence without a US-Soviet war. How China similarly integrates its instruments of statecraft in pursuit of overarching regional and global objectives remains an area that has received abundant speculation but little rigorous study despite its enormous consequences. The coordination and long-term planning involved in grand strategy allow a state to punch above its weight; since China is already a heavyweight, if it has a coherent scheme that coordinates its $14 trillion economy with its blue-water navy and rising political influence around the world—and the United States either misses it or misunderstands it—the course of the twenty-first century may unfold in ways detrimental to the United States and the liberal values it has long championed.

Washington is belatedly coming to terms with this reality, and the result is the most consequential reassessment of its China policy in over a generation. And yet, amid this reassessment, there is wide-ranging disagreement over what China wants and where it is going. Some believe Beijing has global ambitions; others argue that its focus is largely regional. Some claim it has a coordinated 100-year plan; others that it is opportunistic and error-prone. Some label Beijing a boldly revisionist power; others see it as a sober-minded stakeholder of the current order. Some say Beijing wants the United States out of Asia; and others that it tolerates a modest US role. Where analysts increasingly agree is on the idea that China’s recent assertiveness is a product of Chinese President Xi’s personality—a mistaken notion that ignores the long-standing Party consensus in which China’s behavior is actually rooted. The fact that the contemporary debate remains divided on so many fundamental questions related to China’s grand strategy—and inaccurate even in its major areas of agreement—is troubling, especially since each question holds wildly different policy implications.

The Unsettled Debate

This book enters a largely unresolved debate over Chinese strategy divided between “skeptics” and “believers.” The skeptics have not yet been persuaded that China has a grand strategy to displace the United States regionally or globally; by contrast, the believers have not truly attempted persuasion.

The skeptics are a wide-ranging and deeply knowledgeable group. “China has yet to formulate a true ‘grand strategy,’” notes one member, “and the question is whether it wants to do so at all.”12 Others have argued that China’s goals are “inchoate” and that Beijing lacks a “well-defined” strategy.13 Chinese authors like Professor Wang Jisi, former dean of Peking University’s School of International Relations, are also in the skeptical camp. “There is no strategy that we could come up with by racking our brains that would be able to cover all the aspects of our national interests,” he notes.14

Other skeptics believe that China’s aims are limited, arguing that China does not wish to displace the United States regionally or globally and remains focused primarily on development and domestic stability. One deeply experienced White House official was not yet convinced of “Xi’s desire to throw the United States out of Asia and destroy U.S. regional alliances.”15 Other prominent scholars put the point more forcefully: “[One] hugely distorted notion is the now all-too-common assumption that China seeks to eject the United States from Asia and subjugate the region. In fact, no conclusive evidence exists of such Chinese goals.”16

In contrast to these skeptics are the believers. This group is persuaded that China has a grand strategy to displace the United States regionally and globally, but it has not put forward a work to persuade the skeptics. Within government, some top intelligence officials—including former director of national intelligence Dan Coates—have stated publicly that “the Chinese fundamentally seek to replace the United States as the leading power in the world” but have not (or perhaps could not) elaborate further, nor did they suggest that this goal was accompanied by a specific strategy.17

Outside of government, only a few recent works attempt to make the case at length. The most famous is Pentagon official Michael Pillsbury’s bestselling One Hundred Year Marathon, though it argues somewhat overstatedly that China has had a secret grand plan for global hegemony since 1949 and, in key places, relies heavily on personal authority and anecdote.18 Many other books come to similar conclusions and get much right, but they are more intuitive than rigorously empirical and could have been more persuasive with a social scientific approach and a richer evidentiary base.19 A handful of works on Chinese grand strategy take a broader perspective emphasizing the distant past or future, but they therefore dedicate less time to the critical stretch from the post–Cold War era to the present that is the locus of US-China competition.20 Finally, some works mix a more empirical approach with careful and precise arguments about China’s contemporary grand strategy. These works form the foundation for this book’s approach.21

This book, which draws on the research of so many others, also hopes to stand apart in key ways. These include a unique social-scientific approach to defining and studying grand strategy; a large trove of rarely cited or previously inaccessible Chinese texts; a systematic study of key puzzles in Chinese military, political, and economic behavior; and a close look at the variables shaping strategic adjustment. Taken together, it is hoped that the book makes a contribution to the emerging China debate with a unique method for systematically and rigorously uncovering China’s grand strategy.

Uncovering Grand Strategy

The challenge of deciphering a rival’s grand strategy from its disparate behavior is not a new one. In the years before the First World War, the British diplomat Eyre Crowe wrote an important 20,000-word “Memorandum on the Present State of British Relations with France and Germany” that attempted to explain the wide-ranging behavior of a rising Germany.22 Crowe was a keen observer of Anglo-German relations with a passion and perspective for the subject informed by his own heritage. Born in Leipzig and educated in Berlin and Düsseldorf, Crowe was half German, spoke German-accented English, and joined the British Foreign Office at the age of twenty-one. During World War I, his British and German families were literally at war with one another—his British nephew perished at sea while his German cousin rose to become chief of the German Naval Staff.

Crowe argued in his framing of the enterprise, “the choice must lie between . . . two hypotheses”—each of which resemble the positions of today’s skeptics and believers with respect to China’s grand strategy.

Left: British diplomat Eyre Crowe (1864-1925). Date unknown. Author unknown. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Crowe, who wrote his memorandum in 1907, sought to systematically analyze the disparate, complex, and seemingly uncoordinated range of German foreign behavior, to determine whether Berlin had a “grand design” that ran through it, and to report to his superiors what it might be. In order to “formulate and accept a theory that will fit all the ascertained facts of German foreign policy,” Crowe argued in his framing of the enterprise, “the choice must lie between . . . two hypotheses”—each of which resemble the positions of today’s skeptics and believers with respect to China’s grand strategy.23

Crowe’s first hypothesis was that Germany had no grand strategy, only what he called a “vague, confused, and unpractical statesmanship.” In this view, Crowe wrote, it is possible that “Germany does not really know what she is driving at, and that all her excursions and alarums, all her underhand intrigues do not contribute to the steady working out of a well conceived and relentlessly followed system of policy.”24 Today, this argument mirrors those of skeptics who claim China’s bureaucratic politics, factional infighting, economic priorities, and nationalist knee-jerk reactions all conspire to thwart Beijing from formulating or executing an overarching strategy.24

Crowe’s second hypothesis was that important elements of German behavior were coordinated together through a grand strategy “consciously aiming at the establishment of a German hegemony, at first in Europe, and eventually in the world.”26 Crowe ultimately endorsed a more cautious version of this hypothesis, and he concluded that German strategy was “deeply rooted in the relative position of the two countries,” with Berlin dissatisfied by the prospect of remaining subordinate to London in perpetuity.26 This argument mirrors the position of believers in Chinese grand strategy. It also resembles the argument of this book: China has pursued a variety of strategies to displace the United States at the regional and global level which are fundamentally driven by its relative position with Washington.

The fact that the questions the Crowe memorandum explored have a striking similarity to those we are grappling with today has not been lost on US officials. Henry Kissinger quotes from it in On China. Max Baucus, former US ambassador to China, frequently mentioned the memo to his Chinese interlocutors as a roundabout way of inquiring about Chinese strategy.28

Crowe’s memorandum has a mixed legacy, with contemporary assessments split over whether he was right about Germany. Nevertheless, the task Crowe set remains critical and no less difficult today, particularly because China is a “hard target” for information collection. One might hope to improve on Crowe’s method with a more rigorous and falsifiable approach anchored in social science. As the next chapter discusses in detail, this book argues that to identify the existence, content, and adjustment of China’s grand strategy, researchers must find evidence of (1) grand strategic concepts in authoritative texts; (2) grand strategic capabilities in national security institutions; and (3) grand strategic conduct in state behavior. Without such an approach, any analysis is more likely to fall victim to the kinds of natural biases in “perception and misperception” that often recur in assessments of other powers.29

Chapter Summaries

This book argues that, since the end of the Cold War, China has pursued a grand strategy to displace American order first at the regional and now at the global level.

Chapter 1 defines grand strategy and international order, and then explores how rising powers displace hegemonic order through strategies of blunting, building, and expansion. It explains how perceptions of the established hegemon’s power and threat shape the selection of rising power grand strategies.

Chapter 2 focuses on the Chinese Communist Party as the connective institutional tissue for China’s grand strategy. As a nationalist institution that emerged from the patriotic ferment of the late Qing period, the Party now seeks to restore China to its rightful place in the global hierarchy by 2049. As a Leninist institution with a centralized structure, ruthless amorality, and a Leninist vanguard seeing itself as stewarding a nationalist project, the Party possesses the “grand strategic capability” to coordinate multiple instruments of statecraft while pursuing national interests over parochial ones. Together, the Party’s nationalist orientation helps set the ends of Chinese grand strategy while Leninism provides an instrument for realizing them. Now, as China rises, the same Party that sat uneasily within Soviet order during the Cold War is unlikely to permanently tolerate a subordinate role in American order. Finally, the chapter focuses on the Party as a subject of research, noting how a careful review of the Party’s voluminous publications can provide insight into its grand strategic concepts.

Part I begins with Chapter 3, which explores the blunting phase of China’s post–Cold War grand strategy using Chinese Communist Party texts. It demonstrates that China went from seeing the United States as a quasi-ally against the Soviets to seeing it as China’s greatest threat and “main adversary” in the wake of three events: the traumatic trifecta of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the Gulf War, and the Soviet Collapse. In response, Beijing launched its blunting strategy under the Party guideline of “hiding capabilities and biding time.” This strategy was instrumental and tactical. Party leaders explicitly tied the guideline to perceptions of US power captured in phrases like the “international balance of forces” and “multipolarity,” and they sought to quietly and asymmetrically weaken American power in Asia across military, economic, and political instruments, each of which is considered in the subsequent three book chapters.

Chapter 4 considers blunting at the military level. It shows that the trifecta prompted China to depart from a “sea control” strategy increasingly focused on holding distant maritime territory to a “sea denial” strategy focused on preventing the US military from traversing, controlling, or intervening in the waters near China. That shift was challenging, so Beijing declared it would “catch up in some areas and not others” and vowed to build “whatever the enemy fears” to accomplish it—ultimately delaying the acquisition of costly and vulnerable vessels like aircraft carriers and instead investing in cheaper asymmetric denial weapons. Beijing then built the world’s largest mine arsenal, the world’s first anti-ship ballistic missile, and the world’s largest submarine fleet—all to undermine US military power.

Chapter 5 considers blunting at the political level. It demonstrates that the trifecta led China to reverse its previous opposition to joining regional institutions. Beijing feared that multilateral organizations like Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Forum (ARF) might be used by Washington to build a liberal regional order or even an Asian NATO, so China joined them to blunt American power. It stalled institutional progress, wielded institutional rules to constrain US freedom of maneuver, and hoped participation would reassure wary neighbors otherwise tempted to join a US-led balancing coalition.

Chapter 6 considers blunting at the economic level. It argues that the trifecta laid bare China’s dependence on the US market, capital, and technology—notably through Washington’s post-Tiananmen sanctions and its threats to revoke most-favored-nation (MFN) trade status, which could have seriously damaged China’s economy. Beijing sought not to decouple from the United States but instead to bind the discretionary use of American economic power, and it worked hard to remove MFN from congressional review through “permanent normal trading relations,” leveraging negotiations in APEC and the World Trade Organization (WTO) to obtain it.

Because Party leaders explicitly tied blunting to assessments of American power, that meant that when those perceptions changed, so too did China’s grand strategy. Part II of the book explores this second phase in Chinese grand strategy, which was focused on building regional order. The strategy took place under a modification to Deng’s guidance to “hide capabilities and bide time,” one that instead emphasized “actively accomplishing something.”

Chapter 7 explores this building strategy in Party texts, demonstrating that the shock of the Global Financial Crisis led China to see the United States as weakening and emboldened it to shift to a building strategy. It begins with a thorough review of China’s discourse on “multipolarity” and the “international balance of forces.” It then shows that the Party sought to lay the foundations for order—coercive capacity, consensual bargains, and legitimacy—under the auspices of the revised guidance “actively accomplish something” [积极有所作为] issued by Chinese leader Hu Jintao. This strategy, like blunting before it, was implemented across multiple instruments of statecraft—military, political, and economic—each of which receives a chapter.

Chapter 8 focuses on building at the military level, recounting how the Global Financial Crisis accelerated a shift in Chinese military strategy away from a singular focus on blunting American power through sea denial to a new focus on building order through sea control. China now sought the capability to hold distant islands, safeguard sea lines, intervene in neighboring countries, and provide public security goods. For these objectives, China needed a different force structure, one that it had previously postponed for fear that it would be vulnerable to the United States and unsettle China’s neighbors. These were risks a more confident Beijing was now willing to accept. China promptly stepped up investments in aircraft carriers, capable surface vessels, amphibious warfare, marines, and overseas bases.

Chapter 9 focuses on building at the political level. It shows how the Global Financial Crisis caused China to depart from a blunting strategy focused on joining and stalling regional organizations to a building strategy that involved launching its own institutions. China spearheaded the launch of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the elevation and institutionalization of the previously obscure Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA). It then used these institutions, with mixed success, as instruments to shape regional order in the economic and security domains in directions it preferred.

Chapter 10 focuses on building at the economic level. It argues that the Global Financial Crisis helped Beijing depart from a defensive blunting strategy that targeted American economic leverage to an offensive building strategy designed to build China’s own coercive and consensual economic capacities. At the core of this effort were China’s Belt and Road Initiative, its robust use of economic statecraft against its neighbors, and its attempts to gain greater financial influence.

Beijing used these blunting and building strategies to constrain US influence within Asia and to build the foundations for regional hegemony. The relative success of that strategy was remarkable, but Beijing’s ambitions were not limited only to the Indo-Pacific. When Washington was again seen as stumbling, China’s grand strategy evolved—this time in a more global direction. Accordingly, Part III of this book focuses on China’s third grand strategy of displacement, global expansion, which sought to blunt but especially build global order and to displace the United States from its leadership position.

Chapter 11 discusses the dawn of China’s expansion strategy. It argues that the strategy emerged following another trifecta, this time consisting of Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the West’s poor initial response to the coronavirus pandemic. In this period, the Chinese Communist Party reached a paradoxical consensus: it concluded that the United States was in retreat globally but at the same time was waking up to the China challenge bilaterally. In Beijing’s mind, “great changes unseen in a century” were underway, and they provided an opportunity to displace the United States as the leading global state by 2049, with the next decade deemed the most critical to this objective.

Chapter 12 discusses the “ways and means” of China’s strategy of expansion. It shows that politically, Beijing would seek to project leadership over global governance and international institutions and to advance autocratic norms. Economically, it would weaken the financial advantages that underwrite US hegemony and seize the commanding heights of the “fourth industrial revolution.” And militarily, the PLA would field a truly global Chinese military with overseas bases around the world.

Chapter 13, the book’s final chapter, outlines a US response to China’s ambitions for displacing the United States from regional and global order. It critiques those who advocate a counterproductive strategy of confrontation or an accommodationist one of grand bargains, each of which respectively discounts US domestic headwinds and China’s strategic ambitions. The chapter instead argues for an asymmetric competitive strategy, one that does not require matching China dollar-for-dollar, ship-for-ship, or loan-for-loan.

This cost-effective approach emphasizes denying China hegemony in its home region and—taking a page from elements of China’s own blunting strategy—focuses on undermining Chinese efforts in Asia and worldwide in ways that are of lower cost than Beijing’s efforts to build hegemony. At the same time, this chapter argues that the United States should pursue order-building as well, reinvesting in the very same foundations of American global order that Beijing presently seeks to weaken. This discussion seeks to convince policymakers that even as the United States faces challenges at home and abroad, it can still secure its interests and resist the spread of an illiberal sphere of influence—but only if it recognizes that the key to defeating an opponent’s strategy is first to understand it.

Endnotes

-

1.Harold James, Krupp: A History of the Legendary British Firm (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), 51.

-

2.For this memo, see Li Hongzhang [李鸿章], “Memo on Not Abandoning the Manufacture of Ships” [筹议制造轮船未可裁撤折], in The Complete Works of Li Wenzhong [李文忠公全集], vol. 19, 1872, 45. Li Hongzhang was also called Li Wenzhong.

-

3.Xi Jinping [习近平], “Xi Jinping Delivered an Important Speech at the Opening Ceremony of the Seminar on Learning and Implementing the Spirit of the Fifth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Party” [习近平在省部级主要领导干部学习贯彻党的十九届五中全会精神专题研讨班开班式上发表重要讲话], Xinhua [新华], January 11, 2021.

-

4.Evan Osnos, “The Future of America’s Contest with China,” The New Yorker, January 13, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/01/13/the-future-of-americas-contest-with-china.

-

5.For example, John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy during the Cold War (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2005).

-

6.Robert E. Kelly, “What Would Chinese Hegemony Look Like?,” The Diplomat, February 10, 2014, https://thediplomat.com/2014/02/what-would-chinese-hegemony-look-like/; Nadège Rolland, “China’s Vision for a New World Order” (Washington, DC: The National Bureau of Asian Research, 2020), https://www.nbr.org/publication/chinas-vision-for-a-new-world-order/.

-

7.See Yuan Peng [袁鹏], “The Coronavirus Pandemic and the Great Changes Unseen in a Century,” [新冠疫情与百年变局], Contemporary International Relations [现代国际关系], no. 5 (June 2020): 1–6, by the head of the leading Ministry of State Security think tank.

-

8.Michael Lind, “The China Question,” Tablet, May 19, 2020, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/china-strategy-trade-lind.

-

9.Graham Allison and Robert Blackwill, “Interview: Lee Kuan Yew on the Future of U.S.-China Relations,” The Atlantic, March 5, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/china/archive/2013/03/interview-lee-kuan-yew-on-the-future-of-us-china-relations/273657/.

-

10.Andrew F. Krepinevich, “Preserving the Balance: A U.S. Eurasia Defense Strategy” (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, January 19, 2017), https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/Preserving_the_Balance_%2819Jan17%29HANDOUTS.pdf.

-

11.“GDP, (US$),” World Bank, 2019, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gdp.mktp.cd.

-

12.Angela Stanzel, Jabin Jacob, Melanie Hart, and Nadège Rolland, “Grand Designs: Does China Have a ‘Grand Strategy’” (European Council on Foreign Relations, October 18, 2017), https://ecfr.eu/publication/grands_designs_does_china_have_a_grand_strategy/#.

-

13.Susan Shirk, “Course Correction: Toward an Effective and Sustainable China Policy” (remarks, National Press Club, Washington, DC, February 12, 2019), https://asiasociety.org/center-us-china-relations/events/course-correction-toward-effective-and-sustainable-china-policy.

-

14.Quoted in Robert Sutter, Chinese Foreign Relations: Power and Policy since the Cold War, 3rd ed. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012), 9–10. See also Wang Jisi, “China’s Search for a Grand Strategy: A Rising Great Power Finds Its Way,” Foreign Affairs 90, no. 2 (2011): 68–79, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2011-02-20/chinas-search-grand-strategy.

-

15.Jeffrey A. Bader, “How Xi Jinping Sees the World, and Why” (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 2016), http://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/xi_jinping_worldview_bader-1.pdf.

-

16.Michael Swaine, “The U.S. Can’t Afford to Demonize China,” Foreign Policy, June 29, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/06/29/the-u-s-cant-afford-to-demonize-china/.

-

17.Jamie Tarabay, “CIA Official: China Wants to Replace US as World Superpower,” CNN, July 21, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/07/20/politics/china-cold-war-us-superpower-influence/index.html. Daniel Coats, “Annual Threat Assessment,” (testimony, January 29, 2019), https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/Newsroom/Testimonies/2019-01-29-ATA-Opening-Statement_Final.pdf.

-

18.Alastair Iain Johnston, “Shaky Foundations: The ‘Intellectual Architecture’ of Trump’s China Policy,” Survival 61, no. 2 (2019): 189–202, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2019.1589096; Jude Blanchette, “The Devil Is in the Footnotes: On Reading Michael Pillsbury’s The Hundred-Year Marathon” (La Jolla, CA: UC San Diego 21st Century China Program, 2018), https://china.ucsd.edu/_files/The-Hundred-Year-Marathon.pdf.

-

19.Jonathan Ward, China’s Vision of Victory (Washington, DC: Atlas Publishing and Media Company, 2019); Martin Jacques, When China Rules the World: The Rise of the Middle Kingdom and the End of the Western World (New York: Penguin, 2012).

-

20.Sulmaan Wasif Khan, Haunted by Chaos: China’s Grand Strategy from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018); Andrew Scobell, Edmund J. Burke, Cortez A. Cooper III, Sale Lilly, Chad J. R. Ohlandt, Eric Warner, J.D. Williams, China’s Grand Strategy Trends, Trajectories, and Long-Term Competition (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2020), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2798.html.

-

21.See Avery Goldstein, Rising to the Challenge China’s Grand Strategy and International Security (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005); Aaron L. Friedberg, A Contest for Supremacy: China, America, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012); David Shambaugh, China Goes Global: The Partial Power (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2013); Ashley J. Tellis, “Pursuing Global Reach: China’s Not So Long March toward Preeminence,” in Strategic Asia 2019: China’s Expanding Strategic Ambitions, eds. Ashley J. Tellis, Alison Szalwinski, and Michael Wills (Washington, DC: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2019), 3–46, https://www.nbr.org/publication/strategic-asia-2019-chinas-expanding-strategic-ambitions/.

-

22.For the full text, as well as the responses to it within the British Foreign Office, see Eyre Crowe, “Memorandum on the Present State of British Relations with France and Germany,” in British Documents on the Origins of the War, 1898–1914, eds. G. P. Gooch and Harold Temperley (London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1926), 397–420.

-

23.Ibid., 417.

-

24.Ibid., 415.

-

25.Ibid., 415.

-

26.Ibid., 414.

-

27.Ibid., 414.

-

28.Interview.

-

29.Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976).

About the Author

Rush Doshi

Former Brookings Expert

Rush Doshi was the director of the Brookings China Strategy Initiative and a fellow in Brookings Foreign Policy. He was also a fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center and part of the inaugural class of Wilson China fellows. His research focused on Chinese grand strategy as well as Indo-Pacific security issues. He is currently serving in the Biden administration.

If China Ran the World A Chinese order would displace the United States as the world's leader

https://claremontreviewofbooks.com/if-china-ran-the-world/

book reviewed

The Long Game: China's Grand Strategy to Displace American Order

Denial, the first stage of grief according to Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, characterizes America’s responses to the rise of China. Rush Doshi’s account of China’s global strategy in The Long Game is a welcome draft of cold air. China’s strength, he notes more than once, rests on an economy 25% larger than America’s, adjusted for relative prices. Its command of transport and communications technologies allows it to “lock in its ties with Asian states” as well as others.

Doshi is now a Director for China at the National Security Council. Before that he directed the China Initiative at the Brookings Institution, where he advised Kurt Campbell, the Biden Administration’s policy chief for the Indo-Pacific region. Doshi’s standing in Washington ensures a wide audience for a book well worth reading on its own merits. From extensive study of Chinese government and semi-official documents, he has distilled what he believes to be a Chinese “grand strategy” to replace the American postwar world order with one of China’s design.

Doshi seeks an alternative to “those who advocate a counterproductive strategy of confrontation or an accommodationist one of grand bargains, each of which respectively discounts US domestic headwinds and China’s strategic ambitions.” “Both efforts,” he argues, “each backed by widely opposed parts of the policy debate, ultimately flow from a similar set of strained and idealistic assumptions about Washington’s ability to influence the politics of a powerful, sovereign country.”

As a result, “[e]fforts to subvert China’s government are particularly dangerous,” less likely to succeed than to “produce all-out confrontation that could transform the competition from one that is over order to one that is fundamentally existential.” On this I agree with Doshi emphatically. Real per-capita consumption has grown by an order of magnitude in the four decades since Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, and the Chinese people have a vivid recollection of the instability that preceded them.

* * *

Doshi is interested in power rather than posturing. He mentions China’s Uyghurs only once and in passing, and the matter of human rights plays a peripheral role in his story. His theme is what he calls China’s plan “to shape the twenty-first century, much as the US shaped the twentieth.” This he views through an American mirror. Unlike studies that “analyzed the theory and practice of US ‘strategies of containment’ toward the Soviet Union during the Cold War, this book seeks to analyze the theory and practice of China’s ‘strategies of displacement’ toward the United States after the Cold War.”

China’s long project, he writes, “rests on military, economic and political foundations.” The salient military component is “a navy capable of amphibious operations, sea control and distant blue-water missions.” Crucial economic elements include infrastructure spending, “coercive economic statecraft,” and the pursuit of technological superiority over Western nations. In the political realm, China seeks to “shape global information flows in ways that reinforce its narratives.”

Doshi is most at home in the arcana of academic political science, parsing the alphabet soup of international agencies. He seems to think that the United Nations is a central Chinese target: “Beijing has seized on US inattention and worked diligently to place its officials in the top leadership spots of four of fifteen UN specialized agencies.”

His superficial knowledge of the technological and financial battlefronts is, by contrast, the book’s main weakness. Doshi’s idea of what Chinese ambitions might entail is too general to allow for a clear distinction between things China might like to have in the future and matters of raison d’état. He correctly says that a “Chinese order” would entail “displacing the United States as the world’s leading state.” In this new dispensation, “Beijing would project leadership over global governance and international institutions, advance autocratic norms at the expense of liberal ones, and split American alliances in Europe and Asia.”

* * *

That is well and good, but what does it mean for Taiwan? Nowhere does Doshi explain why, or in what way, Taiwan is a prospective casus belli for Beijing. He makes a cogent case that “a decision by Washington to voluntarily terminate its commitment to Taiwan will startle US allies in the region,” who would come to doubt American commitments to them. Doshi implies that what China wants from Taiwan is “geostrategic advantages.”

But that is not how Beijing sees the matter. China is not a nation-state but an empire with seven major languages and 300 minor ones, where only one citizen in ten speaks fluent Mandarin. The existential fear of every Chinese dynasty is that one rebel province will set a precedent for others, leading to fracture along ethnic and geographical lines, as occurred so often in China’s tragic past. Xi Jinping told President Barack Obama at the 2014 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit: “China is a land and a people. Sometimes the population increases by ten percent, sometimes it falls by ten percent. But China’s land is sacred and inviolable and there is nothing we will not do to defend it.”

China insists on sovereignty over Taiwan not because the island has a strategic utility, nor because it wants to suppress its democratic system, but because the integrity of China’s territory is an existential question for the Chinese state. The only alternative to the status quo is a war that no one would win. But to maintain the status quo the United States must neither show the weakness that would tempt China to annex Taiwan, nor the strength that might make Beijing believe that it is plotting to sever a sovereign Taiwanese state from the mainland.

* * *

All the United States military’s war games involving a mainland assault on Taiwan have ended in American defeat. China is building toward 100,000 marines and mechanized infantry poised to invade the island, more than 50 submarines, and a formidable land-to-sea missile capability that could probably destroy most American surface ships operating close to China’s coast. As the editors of the Chinese official English-language newspaper Global Times wrote on July 28, 2021:

The US Navy’s advantage in overwater power will surely persist for some time. China must not only catch up with the US, but also strengthen its land-based missile forces that can strike large US battleships in the South China Sea in a war. We can massively expand this force so that if the US provokes a military confrontation in the South China Sea, all of its large ships there will be targeted by land-based missiles at the same time.

Michèle Flournoy, a former undersecretary of defense in the Obama Administration, argued in Foreign Affairs last year that deterring China requires the U.S. to possess “the capability to credibly threaten to sink all of China’s military vessels, submarines, and merchant ships in the South China Sea within 72 hours.” The clear counterpart to such a force, however, would be China’s credible capability to eliminate U.S. forces in the South China Sea and nearby military facilities even faster, thereby deterring American military initiatives and responses.