风萧萧_Frank

以文会友“我们时代的关键问题”:与亨利·基辛格谈中美关系

2018 年 9 月 20 日

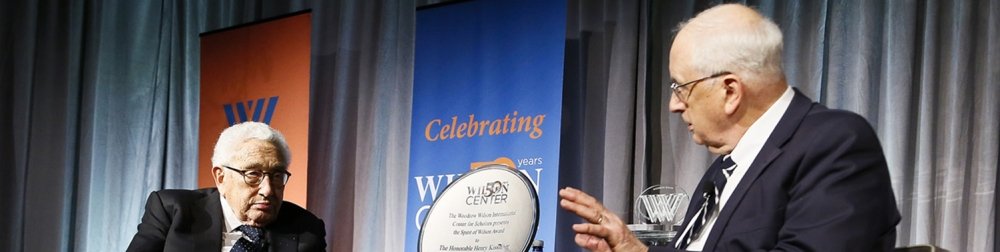

9月13日,威尔逊中心举办庆祝成立50周年暨基辛格中美研究所成立10周年庆典活动。 1973 年至 1977 年担任美国国务卿的亨利·基辛格荣获首届威尔逊精神奖,并参加了与基辛格研究所名誉创始所长、杰出学者 J. Stapleton “Stape” Roy 大使的对话。

基辛格中美研究所

美国外交政策WILSON@50中国大陆

9月13日,威尔逊中心举办庆祝成立50周年暨基辛格中美研究所成立10周年庆典活动。 1973 年至 1977 年担任美国国务卿的亨利·基辛格荣获首届威尔逊精神奖,并参加了与基辛格研究所名誉创始所长、杰出学者 J. Stapleton “Stape” Roy 大使的对话。

这是他们的谈话记录:

Stape Roy:亨利,我们真的很高兴,通过你的意志力,你能够将飓风转移到更南的地方(笑声),并从纽约来到这里。 在理查德·艾克森的非凡介绍之后,我觉得我真的应该向您询问铜价和此类问题。 但我不会。

五十年前,威尔逊中心成立的同一年,您还是纳尔逊·洛克菲勒的外交政策顾问,苏联是我们的主要敌人。 当时您写了一篇关于“美国外交政策的核心问题”的非常有洞察力的文章。 尽管国际体系已经发生了巨大变化,您当时的许多观察仍然具有现实意义。

[对观众。]你可以在网上找到这篇文章。 我想你会惊讶地发现他当时的评论与当前的情况有多么相关。 [对基辛格博士]你当时说过,“在未来的岁月里,美国政策面临的最深刻的挑战将是哲学上的,即在世界上发展某种秩序概念,这个世界在军事上是两极的,但在政治上是多极的。” 当然,当时的军事两极化是在美国和苏联之间。 50年后的今天,许多美国人看到美国和中国之间正在出现军事两极化,而政治多极化涉及的国家在经济和军事上都比50年前强大得多。

您认为您当时的观察今天仍然适用吗? 美国和中国能否共同努力创建稳定的世界新秩序? 或者我们注定会因为对世界秩序的不同看法而与中国陷入对抗性斗争吗? 这与当前美国和中国之间迫在眉睫的贸易战有关,而贸易战是现有世界秩序的重要组成部分。

亨利·基辛格:首先,让我表达我对被邀请来到这里的感激之情,与这么多来自我们两党的朋友和人士一起,我有幸与他们一起工作了几十年。 斯塔普是我关于中国的老师。 当我开始研究中国关系时,我认为我的主要资格是尼克松总统得出的结论,因为我是他的幕僚,所以我是在到达那里之前最不可能泄露此事的人[笑声]。 因此,对我来说,与中国的关系是一个教育和经历的过程。 几十年来我形成的一个基本信念是,我们两国拥有独特的历史机遇。

我们是两个具有相当大破坏能力的国家。 我们两个国家都相信自己在政策实施方面具有特殊性:我们以民主宪政的政治制度为基础;我们以民主宪政为基础。 中国的演变至少可以追溯到孔子和几个世纪的独特实践。

这是我们这个时代的关键问题。 我们每个人都足够强大,能够在世界各地创造可以强加自己偏好的局面,但这种关系的重要性在于双方是否能够相信他们已经取得了足够的成就,足以与他们的信念和历史相一致。

但我们现在所处的位置远远超出了我在 Stape 善意提及的文章中所写的内容。 因为我们所处的位置是,世界的和平与繁荣取决于中国和美国是否能够找到一种合作的方法,并不总是达成一致,而是处理我们的分歧。

而且,还要制定目标,使我们更加紧密地联系在一起,并使世界能够找到一种结构。

这是我们这个时代的关键问题。 我们每个人都足够强大,能够在世界各地创造可以强加自己偏好的局面,但这种关系的重要性在于双方是否能够相信他们已经取得了足够的成就,足以与他们的信念和历史相一致。 这是一项艰巨的任务。 世界上从未有任何两个国家进行过系统性的尝试。 但是,当我读到当代争端时,例如,关于贸易问题的争端,当然,作为一个美国人,我看到了我们提出的一些主张的相当大的优点。

但我也希望能够找到一种方式,让双方在达成协议后都能相信这是他们能够继续运作的基础。 因此,这确实是伍德罗·威尔逊中心值得反思的一个好问题。 这里的问题不是胜利。 问题是连续性、世界秩序和世界正义,看看我们两国能否找到一种方式来相互讨论。 他们将无法欺骗对方; 他们都足够聪明,能够理解他们正在做的事情的含义。

美国人列出了他们想要在不久的将来解决的问题清单; 中国人有一个他们想要努力实现的目标。 所以我们双方都可以互相学习,也需要互相学习。

因此,这就是我想传达的主要信息:中国有一种概念性的政策方法。 他们将其视为一个过程,回溯到某个时期并无限期地向前推进。 美国人非常务实,当美国和中国谈判代表见面时,他们通常有两个不同的议程。 美国人列出了他们想要在不久的将来解决的问题清单; 中国人有一个他们想要努力实现的目标。 所以我们双方都可以互相学习,也需要互相学习。

我们还有一个额外的问题,那就是:技术的快速发展使我们陷入了这样一种境地:世界不仅会受到我们自己设定的目标的影响,还会受到我们的机器在运行过程中为自己设定的目标的影响。 符合我们认为的原创设计。 前所未有的挑战。 所以,我有信心我们会遇到它,因为我们别无选择。

因此,当你在报纸上读到潜在的冲突时,我们应该记住第一次世界大战的历史。如果参加那场战争的领导人知道结果会怎样,他就不会这样做。 没有一位领导人认为这会扰乱原本的生活结构。 我们知道冲突会造成什么后果,因此我相信我们会取得进展。 对于那些想知道这里是否提供早餐的人,我将简短地阐述我的其他观点。 [笑声,掌声。]

Stape Roy:让我们提前 50 年。 几周前,《每日野兽报》撰文称,您曾建议特朗普总统与俄罗斯合作,在中国打拳击。 这让我想到了把中国放进盒子里的想法,我认为这并不能反映你的确切观点。 但这是否准确地描述了您的观点,或者是否丢失了一些重要的细微差别? 您对处理美国与俄罗斯和中国的关系有何看法?

亨利·基辛格:我希望我能在某个场合被邀请,在观众面前向特朗普总统讲述我对这种关系的战略看法。 那篇特别的文章是一篇伟大的小说。 [笑声]但是理解这一点很重要,我之前已经向你们描述过。

我将中国视为构建世界秩序的潜在合作伙伴。 当然,如果不成功,我们就会处于冲突的境地,但我的想法是基于避免这种情况的需要。 因此,我们的问题不是在世界各地寻找盟友来对抗中国。

我们的根本问题应该是找到解决我们双方都关心的一些问题的办法。 因此,这种通过寻找额外盟友来对抗一个我们应该与之建立合作关系的国家来组建新政府的特殊做法是不正确的。 谈论它的唯一原因是因为它说明了当今世界的一些重要问题:中国和美国都不需要盟友来互相争斗。 我们需要的是我们可以共同努力限制冲突的概念。 这就是我的基本观点。

我们都是爱国者,如果发生冲突,我们会支持我们的国家。 但我们的任务是防止并超越这种冲突。

斯塔普·罗伊:谢谢。 [掌声]我还有数千个问题要问你们,但我被告知我有责任让你们回到——

亨利·基辛格:好吧,我们再谈一个。

斯塔普·罗伊:好的。 [笑声,掌声]好吧,让我们为你尝试另一个简单的,这样你就可以休息一会儿。 [笑声]最近有各种各样的说法称美中政策是失败的,因为其核心原则之一是经济发展将把中国转变为自由民主国家,而这也被作为我们政策的目标提出。 。 但这显然还没有发生。

然而,在 50 年前那篇关于美国外交政策核心问题的文章中,你写道,我引用了:“美国关于政治结构的主流观点是,政治结构将或多或少自动地跟随经济进步,并且 它将采取宪政民主的形式。” 所以,这个概念是经济发展产生政治变革,而这种变革的本质就是宪政民主。

但你接着说:“这两种假设都受到严重质疑。” 正如您在文章中所解释的那样,在您的评估中,“在每一个发达国家,政治稳定都是在工业化进程之前发生的,而不是在工业化进程中产生的。事实上,带来工业化的政府制度,无论是民众的还是专制的,都倾向于 这一成就将得到证实,而不是彻底改变。” 本书写于中国实施改革开放政策之前的十年,开启了数十年的经济快速发展。

您认为中国40年的发展证实了您50年前的假设吗?

亨利·基辛格:这是两个不同的问题。 一,就是你提出的:中国过去40年的发展证明了政治演变的过程是什么?

斯塔普·罗伊:对。

亨利·基辛格:第二个问题是:美国外交政策的目的是不是希望我们采取的具体措施能够产生一定的效果?

这里有几个阶段。 在中美关系的第一阶段,我认为中美双方都将对方视为对抗苏联威胁的制衡力量,这一说法是正确的。 我们向当时与我们没有任何关系的中国开放,以便为俄罗斯人、苏联人引入额外的计算要素。 而且,为了给我们自己的人民带来希望,在越南战争和国内分裂时期,他们的政府有一个和平世界的愿景,其中包括了被排除在外的因素。

我想说,我们希望双方的价值观能够更加接近。 但我们认为,为了维护和平与稳定,我们有义务不把中国的转型作为一个阻碍其他一切的目标。

这是我们的两个主要目标。 这些目标之所以能够实现,是因为中国有着同样的目标。 随着时间的推移,中国经济的发展速度远远超出了任何人的预期。 一开始,我们达成了一些交易,从纯粹的经济角度来看,这些交易似乎对中国有利。 但我们制造它们是因为我们认为中国实力的增长弥补了苏联的不平衡。

然后,随着时间的推移,中国的发展如此之快,以至于为早期没有人预见到的经济发展创造了可能性。 在此过程中,需要某种程度平等平衡的正常商业考虑变得越来越占主导地位。 这是目前讨论的基础,我相信,当双方冷静考虑时,一定会找到解决方案。

另一个问题是,美国的政策是否系统地试图在中国实现民主? 这是一个非常难以回答的问题。

作为美国人,尤其是像我这样的移民,美国民主是一次奇妙的经历。 当我来到这个国家时,我 15 岁,有人要求我写一篇关于作为美国人意味着什么的文章。 我写道,“对我来说,最重要的事情是能够昂首挺胸地走在街上”,所以这很重要。 但当你制定外交政策时,有时你必须权衡短期内可以实现的目标与需要演变的目标。 中国人几千年来一直在办自己的事。

所以,我想说,我们希望双方的价值观能够更加接近。 但我们认为,为了维护和平与稳定,我们有义务不把中国的转型作为一个阻碍其他一切的目标。

所以,这仍然是我目前对美国总体态度的看法。 我们无法解决世界上所有的问题和世界上所有国家的国内结构。 作为一项国家努力,我们必须在这个方向上有目标,并且我们必须尽可能地推动它。

根据我的经验——不是与中国——我们在犹太移民问题上与俄罗斯发生了问题,尼克松上台时,犹太移民数量约为 700 人。我打电话给俄罗斯大使,我说:“通常不考虑移民问题。” 一个国际问题。但我们会观察你的所作所为,不是作为条件,而是我们会观察,我们会根据你的行为做出回应。” 因此,我们试图将其从讨价还价转变为哲学问题,三年内移民人数从 700 人增加到 37,000 人。 然后它成为美国国内政治的一个问题,人数再次大幅下降,降至 15,000。

所以,我对中国的看法是,就我们对世界的影响而言,美国的表现是影响其他国家的最佳方式。 而且,虽然我当然更喜欢——出于我给出的原因——我们的制度,但我也相信我们必须对其持久影响有足够的信心,不让它成为我们和其他国家之间的强权政治问题,具体取决于具体情况 。 这是我的总体看法。

但我的观点重要的是,你应该选择促进和平与进步的目标,你必须努力实现合作,但你不能用短期压力来逆转历史的演变。

我认为,随着国家的发展,存在一定的现实——人们从农村向城市流动的影响、教育制度调整的影响——而这些现实带来了变化。 我们会坚持我们所宣誓的,但我们不会把它变成我们和中国之间的权力问题。

有很多我非常尊敬的人有不同的观点。 但我的观点重要的是,你应该选择促进和平与进步的目标,你必须努力实现合作,但你不能用短期压力来逆转历史的演变。

这是一个重要的话题,将在我们国家进行讨论。 我希望有些人认为我们必须永久地寻求强加我们的偏好。 威尔逊中心将举办许多关于该主题的研讨会。

Stape Roy:最后一个简单的问题。 这是一个“是否”的问题,而不是一个“如何”的问题。 不久前,参谋长联席会议主席向国会作证称,到2025年,中国将成为美国的主要威胁。 如果你是国务卿,你会接受这一评估作为已成定局吗? 或者你是否相信巧妙的外交有可能使中国变得更强大,而不对美国构成威胁?

亨利·基辛格:这个问题可以从两个层面来回答。 第一,我不希望2025年出现中国军事力量强于美国的情况。 我始终赞成一项能让我们强大到足以应对可预见的危险的军事政策。 因此,随着中国或俄罗斯或其他国家的发展,我会努力确保我们永远不会陷入这种境地。 但同时,我认为,中国和美国在寻求安全的同时,必须进行对话,避免威胁彼此的利益,并寻求发展一些合作项目, 让人们更加紧密地联系在一起。

当我成为国家安全顾问时,我当然意识到了我们的战争计划,并且我意识到战争的后果是巨大的。 因此,在某种程度上,我们被迫讨论这些影响。 现在我们已经领先了很多步。 危险要大得多。

因为,作为战略学的学生,我们不能以以往战争的模式来想象先进高科技国家之间的战争。 它们涉及一定程度的破坏、一定程度的沟通和相互影响,可以肯定地说,世界将永远不再一样。 因此,我认为实现这一政治条件应该成为美国外交政策的目标。 我还认为,我们永远不应该处于无法寻求安全的境地。 所以我会尝试两者兼而有之,但我会尝试在牢记对话的同时完成安全要素。

我只想回到我之前提出的一个技术观点。 当我成为国家安全顾问时,我当然意识到了我们的战争计划,并且我意识到战争的后果是巨大的。 因此,在某种程度上,我们被迫讨论这些影响。 现在我们已经领先了很多步。 危险要大得多。 这些武器的复杂性甚至还没有被完全了解。 因此,这种讨论总是必须进行,这样我们就不会因沟通不畅或意外而随波逐流。

但我想让你们所有人相信,我认为这是可以解决的,而且我不认为这是不可避免的,而且我认为这应该在没有战争的情况下实现。 这些是基本原则。

斯塔普·罗伊:谢谢。 [掌声]

'The Key Problem of Our Time': A Conversation with Henry Kissinger on Sino-U.S. Relations

September 20, 2018

On September 13, the Wilson Center hosted a gala event to mark the 50th anniversary of its founding and the 10th anniversary of its Kissinger Institute on China and the United States. Henry Kissinger, U.S. secretary of state from 1973 to 1977, was presented with the inaugural Spirit of Wilson Award and participated in a conversation with Ambassador J. Stapleton “Stape” Roy, founding director emeritus and a distinguished scholar at the Kissinger Institute.

On September 13, the Wilson Center hosted a gala event to mark the 50th anniversary of its founding and the 10th anniversary of its Kissinger Institute on China and the United States. Henry Kissinger, U.S. secretary of state from 1973 to 1977, was presented with the inaugural Spirit of Wilson Award and participated in a conversation with Ambassador J. Stapleton “Stape” Roy, founding director emeritus and a distinguished scholar at the Kissinger Institute.

This is a transcript of their conversation:

Stape Roy: Henry, we are really delighted that, through the power of your will, you were able to divert the hurricane further south [laughter], and make it here from New York. After that extraordinary introduction by Richard Ackerson, I feel I really should be asking you about copper prices and issues of that sort. But I'm not going to.

Fifty years ago, the same year when the Wilson Center was established, you were still a foreign policy advisor to Nelson Rockefeller, and the Soviet Union was our principal enemy. At that time, you wrote a very perceptive essay on "Central Issues of American Foreign Policy." Many of your observations at that time are still relevant today, even though the international system has changed enormously.

[To the audience.] You can find that essay online. I think you will be stunned to find how relevant his comments at that time are to the current situation. [To Dr. Kissinger.] You said then, "In the years ahead, the most profound challenge to American policy will be philosophical, to develop some concept of order in the world, which is bipolar militarily but multipolar politically." At that time, of course, the military bipolarity was between the United States and the Soviet Union. Now, 50 years later, many Americans see an emerging military bipolarity between the United States and China, while the political multipolarity involves countries economically and militarily much more powerful than the countries were 50 years ago.

Do you think that your observations at that time are still relevant today? Can the United States and China work together to create a stable new world order? Or are we doomed to end up in confrontational struggle with China over our differing views of what the world order should be? This is relevant to the current trade war looming between the United States and China, which is an important part of the existing world order.

Henry Kissinger: Well, first of all, let me express my appreciation for having been asked to come here, with so many friends and people from both of our parties with whom I've had the honor of working over all these decades. And Stape was my teacher about China. When I started on Chinese relations, I think my principal qualification was that President Nixon concluded, since I was on his staff, I was the least likely person to leak about it before I got there [laughter]. So, for me, relations with China have been a process of education and experience. And a fundamental conviction I developed, over the decades, is that our two countries have a unique historic opportunity.

We are two countries that have considerable destructive capabilities. We are two countries that believe they have an exceptional nature in the conduct of policy: we on the basis of the political system of democratic constitutionalism; China on the basis of an evolution that goes back at least to Confucius and centuries of unique practice.

This is the key problem of our time. Each of us is strong enough to create situations around the world in which it can impose its preferences, but the importance of the relationship will be whether each side can believe that they have achieved enough to be compatible with their convictions and with their histories.

But we are now in a position that goes far beyond what I wrote about in the article that Stape has been kind enough to mention. Because we're in a position in which the peace and prosperity of the world depend on whether China and the United States can find a method to work together, not always in agreement, but to handle our disagreements. But also, to develop goals which bring us closer together and enable the world to find a structure.

This is the key problem of our time. Each of us is strong enough to create situations around the world in which it can impose its preferences, but the importance of the relationship will be whether each side can believe that they have achieved enough to be compatible with their convictions and with their histories. That is a huge task. It's never been attempted systematically by any two nations in the world. But when I read about contemporary disputes, say, about trade issues, of course, as an American, I see considerable merit in some of the propositions we have put forward.

But I also hope that a way can be found by which, when an agreement is reached, both sides can believe that this is a basis from which they can continue to operate. And so, this really is a good question for the Woodrow Wilson Center to reflect on. The issue is not victory, here. The issue is continuity, and world order, and world justice, and to see whether our two countries can find a way of talking about it to each other. And they will not be able to fool each other; they're both intelligent enough to understand the implications of what they're doing.

The Americans have a list of things that they want to fix in the immediate future; the Chinese have an objective towards which they want to work. So we both can learn from each other, and we need to learn from each other.

So, that is the main message I want to leave, that China has a conceptual approach to policy. They look at it as a process, going back a certain period and going forward indefinitely. Americans are very pragmatic, and when American and Chinese negotiators meet, they usually have two different agendas. The Americans have a list of things that they want to fix in the immediate future; the Chinese have an objective towards which they want to work. So we both can learn from each other, and we need to learn from each other.

And we have one additional problem, which is: the rapid evolution of technology has put us into a situation where the world can be affected not only by the goals we set ourselves but the goals our machines decide to set for themselves, as they go along meeting what we think is our original design. An unprecedented challenge. So, I am confident that we will meet it, because we have no other choice.

And so, when you read in the newspapers about a potential conflict, we should remember the history of World War I. Not one of the leaders who entered that war would have done so if he had known what the outcome would be like. Not one of the leaders thought that this would upset the structure of life as it had been. We know what conflict will do, and, therefore, I'm confident that we will make progress. And I'll make my other points shorter, for those of you who wonder whether breakfast will be served here. [Laughter, applause.]

Stape Roy: Let's jump ahead 50 years. Several weeks ago, The Daily Beast wrote an article claiming that you had advised President Trump to work with Russia to box in China. It brought to my mind the idea of putting China into a box, which I didn't think reflected your precise views. But was this an accurate depiction of your views, or were some important nuances somehow lost? What are your thoughts on managing US relations with Russia and China?

Henry Kissinger: I wish I had been invited, on some occasion, to tell President Trump, in front of the audience described, about my strategic views of that relationship. That particular article was a great piece – of fiction. [Laughter.] But the reason it's important to understand this, I've described to you before.

I visualize China as a potential partner in the construction of a world order. Of course, if that does not succeed, we will be in a position of conflict, but my thinking is based on the need to avoid that situation. So, our problem is not to find allies around the world with which to confront China.

Our fundamental problem should be to find solutions to some of the problems that concern us both. So, this particular approach of beginning a new administration with finding an additional ally against a country with which we should have a cooperative relationship is simply not correct. And the only reason to even talk about it is because it illustrates something important about the present world: neither China nor America need allies to fight each other. What we need is concepts by which we can work together to set limits to conflicts. So that is my basic view.

All of us are patriots, and if a conflict arises, we will support our country. But the task is to prevent that conflict, and to transcend it.

Stape Roy: Thank you. [Applause] I have thousands of more questions to ask you, but I am told that I have a responsibility to get you back to –

Henry Kissinger: Well, let's go for another.

Stape Roy: Okay. [Laughter, Applause.] Well, let's try another easy one for you, so you can rest for a moment. [Laughter.] There have been a variety of recent claims that U.S.-China policy has been a failure, because one of its central tenets was that economic development would transform China into a liberal democracy, and that was presented as the goal of our policy. And that clearly has not occurred.

Yet, in that essay on central issues in American foreign policy, 50 years ago, you wrote, and I quote: "The dominant American view about political structure has been that it will follow, more or less automatically, upon economic progress, and that it will take the form of constitutional democracy." So, the concept was that economic development produces political change, and the nature of that change would be constitutional democracy.

But you went on to say: "Both assumptions are subject to serious question." In your assessment then, as you explained in your essay, "In every advanced country, political stability preceded rather than emerged from the process of industrialization. In fact, the system of government which brought about industrialization, whether popular or authoritarian, has tended to be confirmed rather than radically changed by this achievement." This was written 10 years before China adopted its reform and openness policies, which launched its decades of rapid economic development.

Do you believe that China's development over the last 40 years has confirmed your assumptions of 50 years ago?

Henry Kissinger: They're two separate questions. One, it's the one you put: what does Chinese development in the last 40 years prove about the process of evolution of politics?

Stape Roy: Right.

Henry Kissinger: And the second is: was it the purpose of American foreign policy that the specific measures we took would produce certain results?

There have been phases, here. In the first phase of Sino-American relations, I believe it is correct to say that both China and the United States saw in the other a counterweight against a threatening Soviet Union. We opened to China, with which we had no relations to speak of at the time, in order to introduce an additional element of calculation for the Russians, for the Soviets. And also, to give our own people hope that in the period of the Vietnam War and domestic divisions, their government had a vision of a peaceful world that included elements that had been excluded.

I would say our hope was that the values of the two sides would come closer together. But we felt we had an obligation, for the preservation of peace and stability, not to make the transformation of China such a goal that it would stop everything else.

Those were our two principal objectives. And they were achieved because China had the same objective from its side. As time evolved, China developed economically at a pace that was much faster than anybody predicted. And at the beginning, we made a number of deals which, in purely economic terms, seemed to be balanced in favor of China. But we made them because we thought growth in Chinese strength compensated for that imbalance in the Soviet Union.

Then, as time developed, the Chinese evolution was so rapid that it created possibilities for economic development nobody foresaw in the early period. And in the process, normal commercial considerations, which require some degree of equal balance, became more and more dominant. That is the basis for the present discussions, which I believe, when they are calmly considered, will lead both sides to a solution.

The other question is, has American policy systematically attempted to bring about democracy in China? That's a very difficult issue to answer.

As Americans, and particularly as an immigrant, as I am, American democracy is a wondrous experience. When I came to this country, I was 15, and I was asked to write an essay on what it meant to be an American. And I wrote, "The most important thing, to me, is to be able to walk on the street with my head erect," so that's important. But when you conduct foreign policy, you have to weigh, sometimes, the objectives that can be reached in the short-term against the objectives that require evolution. And the Chinese have conducted their own affairs for thousands of years.

So, I would say our hope was that the values of the two sides would come closer together. But we felt we had an obligation, for the preservation of peace and stability, not to make the transformation of China such a goal that it would stop everything else.

So, that is still my present view about the general attitude of the United States. We cannot solve all the problems of the world and the domestic structure of all the countries in the world. As a national effort, we must have objectives in that direction, and we must promote it where we can.

In my experience – not with China – we had a problem with Russia on the issue of Jewish immigration, which when Nixon came into office, amounted to about 700. And I called in the Russian ambassador and I said, "Immigration is not usually considered an international problem. But we will watch what you do, not as a condition, but we will watch and we will respond depending on your conduct." So, we tried to move it from a bargaining to a philosophical issue, and immigration went from 700 to 37,000, in 3 years. Then it became an issue of American domestic politics, and it went way down again, to 15,000.

So, my view on China has been that, in terms of our impact on the world, the American performance has been the best way to influence other countries. And, and while I prefer, of course – for the reasons I gave – our system, I also believe we must have faith enough in its lasting impact not to make it an issue of power politics between us and other countries, depending on the circumstances. That has been my general view.

But my view is importantly dominated by the fact that you should select objectives that promote peace and progress, that you must attempt to achieve cooperation, but you cannot undo historical evolution with short-term pressures.

I think as countries develop, there are certain realities – the impact of the movement of people from the countryside to the cities, the impact of adaptations of the educational system – and they were the ones that have produced changes. We will stand for what we have avowed, but we will not turn it into a power issue between us and China.

There are many people, whom I greatly respect, who have a different view. But my view is importantly dominated by the fact that you should select objectives that promote peace and progress, that you must attempt to achieve cooperation, but you cannot undo historical evolution with short-term pressures.

It's an important topic and it will be discussed in our country. I'd expect some have the view that we must permanently seek to impose our preference. The Wilson Center will have many seminars on that topic.

Stape Roy: One final simple question. It's a 'whether' question, not a 'how' question. Not long ago, the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff testified to congress that, in 2025, China would be the principal threat to the United States. If you were secretary of state, would you accept that assessment as a foregone conclusion? Or would you believe that skillful diplomacy might have the possibility of enabling a stronger China to emerge that was not a threat to the United States?

Henry Kissinger: There are two levels of answering this. One, I would not want a situation to exist in 2025 where China is militarily stronger than the United States. And I would always favor a military policy that keeps us strong enough to deal with foreseeable dangers. And therefore, as China or Russia or countries grow, I would attempt to make sure that we will never get into that position. But simultaneously, I believe that it is essential that China and the United States, while looking for their security, are engaged in a dialogue in which they will seek to avoid threatening each other's interests, in which they will seek to develop some cooperative projects that bring the people closer together.

When I became National Security Advisor, I became conscious, of course, of our war plans, and I realized that the consequences of a war were monumental. And, therefore, in a way, we were driven to discuss these implications. Now we are many steps ahead of that. The danger is much greater.

Because, as a student of strategy, we cannot think of a war between advanced hi-tech countries, in anything like the patterns of previous wars. They involve a level of destruction and a level of communication and impact on each other that it is safe to say that the world will never be the same again. So, I would think it should be an objective of American foreign policy to achieve that political condition. I would also think we should never be in a position where we are not able to look for our security. So I would attempt to do both, but I would attempt to do the security element while keeping in mind a dialogue.

And I just want to come back to one technical point I made before. When I became National Security Advisor, I became conscious, of course, of our war plans, and I realized that the consequences of a war were monumental. And, therefore, in a way, we were driven to discuss these implications. Now we are many steps ahead of that. The danger is much greater. The complexity of the weapons is not even fully understood. So that discussion always has to take place, so that we don't drift by miscommunication or accident.

But I want to leave you all with the conviction that I think this is solvable, and I do not think it is inevitable, and I think it should be achieved without war. Those are the basic principles.

Stape Roy: Thank you. [Applause]