风萧萧_Frank

以文会友The Fed - The Outlook for the U.S. Economy - Federal Reserve Bank

美联储主席谈美国经济挑战:生产率低迷,已接近二战以来最低

|

|

当地时间2018年4月6日,美国芝加哥,美联储主席鲍威尔在芝加哥经济俱乐部发表题为“美国经济前景展望”的演讲。视觉中国 图

中美贸易争端风云迭起,美联储主席则一方面强调了美联储日渐稳健中性的货币政策立场,另一方面也表达了对美国经济长期生产率增长缓慢的担忧。

当地时间4月6日,美联储主席鲍威尔在芝加哥经济俱乐部发表题为“美国经济前景展望”的演讲,这也是鲍威尔第一次在公开场合就美国经济和美联储货币政策进行全面分析。

鲍威尔介绍,美国经济已基本处于充分就业状态,就业市场有望继续保持强劲增长。尽管通胀率仍低于美联储目标,但鲍威尔预计通胀率将在未来几个月上升,并在中期内达到2%的目标。他说,美联储官员对通胀率上升的信心有所增强。

但是与此同时,他也指出经济长期来看美国面临诸多挑战,最主要的问题体现在劳动参与率和生产率低迷,后者已接近二战后的最低水平。

货币政策方面,鲍威尔强调了美联储稳健中性的立场,他表示,如果美国经济继续保持现在的增长势头,美联储进一步渐进加息是合适的。加息过慢有可能导致经济过热,而加息太快则可能抑制通胀率回升,保持渐进的加息节奏可以避免这两种风险。

针对美国政府提高关税的计划,鲍威尔表示,有企业表示贸易政策的变化给其中期经营前景带来风险,但目前关税计划尚未实施,其规模仍存在不确定性。

鲍威尔未对中美的贸易争端作出评价。同日,旧金山联储银行主席威廉姆斯表示,具体的贸易行动并未给经济造成巨大影响。如果爆发贸易战,将给美国经济造成极大的破坏,可能导致通胀攀升。威廉姆斯即将于6月18日就任纽约联储主席。

接下来的一周,中美贸易博弈仍将是多方关注的热点,而美联储3月会议纪要也将发布。

以下为演讲全文:

90多年来,芝加哥经济俱乐部为现在以及未来的领袖们提供了一个讨论攸关国家利益的重要平台。我很荣幸今天在这里发言。

在美联储,我们致力于使我们的经济体足够强劲以使个人、家庭和工商业都受益。国会授予我们的最重要目标——最大就业和物价稳定。今天我将谈谈最近的经济发展状况,主要是劳动力市场和通胀的情况,长期的增长展望,以及货币政策。

美国最近的经济发展状况

金融危机后,美国经济在缓慢复苏。失业率在2009年10月达到10%的历史最高值,而现在已经回落到了4.1%,是20年来的最低值。在这一轮的扩张中已经新增了1700万就业,目前的就业月新增速度完全能满足新进入劳动力市场的数目。劳动力市场非常强劲,我与我的同事,以及公开市场委员会(FOMC)也希望它能保持强劲。通胀水平持续低于FOMC2%的目标,暗示我们希望在未来几个月内这个指标能有所上升,并在中期内稳定在2%左右。

除了劳动力市场,也有其他的指标显示经济正强劲复苏。收入稳步增加,家庭财富增长,消费者信心也在上升,持续支撑消费支出,达到了经济产出的三分之二。工商业投资在持续两年的低迷后,去年也显著改善。财政刺激和宽松的金融环境为家庭支出和商业投资提供了有利支撑,全球经济强劲增长也刺激了美国的出口。

正如在座所知,每个季度FOMC成员会提交哥们各自对增长、就业、通胀和加息路径的预测,这也是委员会制定货币政策的最主要工具。每个人的预测会汇编成《经济预测梗概》(Summary of Economic Projections)发布,FOMC成员需要提前三个星期提交他们的预测结果,也呈现出中期经济前景强劲,也普遍提升了经通胀调整的国内生产总值(GDP)增长预期,也调低了对失业率的预测。此外,很多成员对于通胀回升至2%的信心也在增强。经济增长的前景是较为平衡的。

劳动力市场的状况

正如我刚才提到的,失业率已经降到了2000年左右的水平。3月SEP的中期预测认为失业率在接下来一段时还会跌落4%,这也是20世纪60年带来未曾出现过的。这个强有力的信号对美联储的两个任务非常重要,也对美联储制定货币政策影响重大。

“最大就业”意味着委员会要将劳动力资源最大化。长期来看,最大就业水平不由货币政策决定,而是由劳动力市场的结构和动力决定。而且最大就业不可直接测量得到,它会持续变化。对最大就业的实时评估是高度不确定的。鉴于此,FOMC并不设置固定的最大就业目标,而是测量这个指标的范围,评估经济状况在多大程度称接近最大就业。失业率是最好的衡量劳动力市场的单一指标。目前失业率为4.1%,略微低于FOMC预测的长期失业率中位数。

但是,只看失业率是不行的。按照官方对失业的定义,必须在过去的4个星期中处于积极找工作的状态。如果没有在找工作,就不算是失业。但是从劳动力市场来看,有些人想要工作,也可以工作,而有些在做兼职工作的有可能想要一份全职工作。有些不想要工作的,可能看到有好的机会也加入到劳动力市场中来了。所以,在判断劳动力市场松紧时,我们要看很多其他数据,包括失业率的测量方法,包括空余工作岗位,家庭和商业对劳动力市场的感受以及薪资和物价水平。

|

|

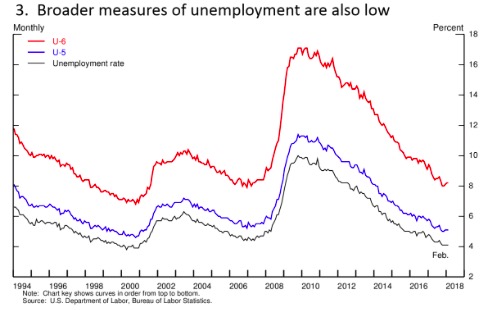

失业率与U5、U6。U5包括失业的与过去1年中都在找工作的人数,U6包括U5和那些正在做兼职且在找全职工作的人数。来源:美联储网站

上图是失业率和两个更宽泛地衡量失业率的指标,我们通常称为U5和U6。U5包括失业的与过去1年中都在找工作的。U6包括U5和那些正在做兼职且在找全职工作的。U5和U6近些年都显著下降,他们现在处于金融危机之前的水平,尽管尚未回到1999年-2000年的低位。

这个图表是20年前雇主雇佣到符合条件的员工的难度,空余岗位率达到历史峰值,也是过去数周的平均水平。家庭反应出工作机会也大幅上升,这与工商企业反应的工作机会一致。此外,员工离职的比率也很高,意味着员工也足够有信心自愿离开现在的工作岗位。

目前来看我们的劳动力市场偏紧,但是其他的数据却并没有那么明朗。劳动参与率,即测量劳动力年龄人口是否在工作或是找工作的指标过去4年较为平稳,没有太大变化。不过由于老龄化人口上升,抑制了劳动参与率,这个数值平稳也是一个好的信号。不过,25-54岁年龄间的劳动参与率也仍未回复至危机前的水平,这意味着有更多的人本应回到劳动力市场。但是同时,强劲的劳动力市场也在将那些离职很久的人拉了回来。例如,有些过去未就业的成年人回到劳动力市场的比例在过去这些年有所上升。

薪资也保持了温和增长,低生产率是近些年薪资未能显著增长的重要原因。同时,这也意味着劳动力市场还不够紧。我也将进一步关注随着劳动力市场持续增强,薪资的增长状况。

据上述数据与指标来看,我们可以说劳动力市场已经达到我们最大就业的目标了吗?由于长期很多指标是不确定的,但是也已经表明很接近最大就业。一些其他的指标仍不够乐观。最大就业的评估是不够确定的,但也得到了修正。委员会将持续关注所有这些指标,以期将劳动力资源得到最大程度的利用。

通胀

劳动力市场虽然得到了根本改善,通胀值却很低,持续低于2%的长期目标。截至2月,消费者价格过去12个月增长了1.8%。核心价格指数(排除了能源和食品的价格)在同一时期里上涨了1.6%。实际上,这些指数在过去6年中都低于2%。通胀持续低于我们的目标导致了一个,即通胀和失业率之间的关系——菲利普斯曲线。既然失业率如此低,为何还看不到更高的通胀?

你们仔细阅读FOMC的会议纪要便可发现,关于通胀变动的讨论贯穿了我们整个1月的会议。几乎所有的成员都认为菲利普斯曲线仍是有效的,但是他们也承认劳动力市场与通胀之间的联系变弱了,也更难预估,反应出美国和其他发达经济体很可能会经历更长时间的低通胀。成员们还发现,通胀预期与能源、进口价格的变动可以影响通胀。

我的观点是这些数据一直呈现出整个国家劳动力市场和通胀的变化。这一联系在过去几十年中虽然变弱,但是也仍持续着,我认为它们也将持续影响货币政策。通胀低迷在前些年可以用高失业率来解释,2015年和2016年则是因为能源价格下跌、美元上涨。可是去年通胀的下降确实一个意外。2017年低于2%的目标反映出,或者至少部分反映出一些反常的价格下跌,例如手机。实际上月度通胀值在过去7个月已经变得更为强劲了,过去12个月的通胀指数也在这个春天有所上升。我一贯坚持我的观点,FOMC成员3月的预测中位数显示今年通胀将上涨至1.9%,2019年将上涨至2%。

长期挑战

虽然新增就业强劲,失业率很低,美国经济却面临一些长期的挑战。在这一次经济扩张中,GDP年平均增速刚刚超过2%,远低于此前的扩张。虽然这几个季度的增速更快,但与危机之前相比也还是很低。可是,失业率在这一次扩张中下跌了6个百分点,这也意味着这一次增长扭转了劳动力市场的局面。FOMC对经济增长的预测中位数为1.8%。来自Blue-Chip私人预测机构的这个数值为2%左右。

这个问题进一步展开来看,我们来看看劳动率增长的情况。与2001-2007年的那一次增长做一个对比。那一次扩张中,经济增长年均增速接近3%。除了增速更快,年均新增就业却比这一次低0.5%。两者的不同正是生存率的不同,21世纪初期的生产率增速几乎是这一轮扩张的2倍。

长远来看,劳动生产率增速自2010年以来便维持在二战后的最低水平,仅为战后的四分之一的水平。而且这似乎成为一个全球的现象,即便是那些没怎么受金融危机影响的国家也是如此。这一现象表明这不仅仅是美国的问题。

劳动生产率增速受制于商业投资、劳动力的工作经验与技能、科技变革、效率提升(经常附着于其他因素上)等因素。在美国与很多其他国家,劳动生产率下降是因为危机后投资疲软。但是近期投资有所回暖,也表明资本集约度会回升。另一个导致下降的原因是总体生产力增速的下降,其前景也是相当不确定的。整体生产力增速是很难预测的,对此有很多不同的观点。一些人为生产力受制于信息技术革命,现在的科技变革对刺激生产力却帮助不大。有些人则持商业动能论,认为有些员工辞职,去寻找新的工作,导致资本和劳动力向生产力更高的领域移动变缓,从而导致生产力增速下降。

机器人、生物科技和人工智能等新科技领域的突破带来了一些乐观的观点。他们认为根本的生产力增长在于能源生产和电商领域的创新,乐观主义者们指出科技的进步经常需要数十年的时间才会在经济中反应出来,对生产力的影响也是如此。从蒸汽机和电力的运用中都可以看到这一迟滞,这两项创新最终都带来了生产力的大幅提升。按照这个观点,我们只需对新科技保持耐心。只有时间可以告诉我们哪个观点更好,我们也没法依此就预测接下来生产力就会增长。

另一个有助于产出增长的重要指标是工作时长。2010年以来这个数值已经年均增长0.5%,低于10年前的数值。有可能是因为婴儿潮出生的人群逐渐成为老龄人群,这一趋势也仍将持续。另一个原因是25-54岁人群的劳动生产率从2010年-2015年后持续下降,现在仍处于低位。这个数值几乎下降了超过50年,其间女性的参与率自20世纪90年代有所提升,而后又转为下降,也已下降了20年左右。

这一趋势在美国比在其他发达经济体要更为严重。20世纪90年代,与其他国家相比,美国的女性劳动参与率相当高。但是现在这一数值上,美国仅高于意大利,低于德国、法国和西班牙。

黄金年龄劳动参与率下降的原因目前没有共识。虽然全球化和自动化会影响国内的生产率和增长,导致没有大学学位和制造业工人失业。但是除此之外,近几十年来残障人士人数增加,阿片样物质(成瘾性药物)泛滥有可能导致黄金年龄雇员数下降。由于美国的这个数值比其他国家都大,应该是有一些美国独有的原因起到了主要作用。正如我前面说的,一个强劲的经济体可能持续将这个年龄段的人群带回劳动力市场,也可以减少离开劳动力市场的人数。研究表明结构性措施是有利于提升这个年龄群体的劳动力参与率的,例如提升教育水平,反对滥用成瘾性药物等。

总而言之,这些影响长期增长的因素仍在持续,尤其是劳动力市场增长缓慢。其他的数值则很难预测,例如生产力。我们可以采取措施提升劳动参与率,并且保持生产率的持续增长。美联储并没有做到这一点的政策工具,包括提升教育和工作技能方面的投资、工商业投资与基础设施投资等等。

货币政策

金融危机之后,FOMC在提升就业,防止通胀下降方面做出了努力。随着经济持续复苏,减少货币政策的支持也是合适的。如果等到通胀和就业达到我们的目标之后再收紧,有可能使通胀过热。基于这个理由,货币政策如果突然收紧,有可能刺激到经济,甚至引发衰退。

所以,为了支撑经济持续扩张FOMC采取渐进路径减少货币政策的支持。我们2015年12月开始加息,从那以来,经济持续扩张,但是通胀仍然很低迷,委员会也持续在加息。委员会保持耐心,也会减少无法预期的情况的风险,防止经济再度衰退到需要联邦基金利率再次回到零(虽然它仍是有效的),因此我们将主动缩紧宽松的货币政策。

再次,去年10月FOMC开始渐进地缩减资产负债表,减少我们的债券持有也是将货币政策保持中性的另一种方式。缩表的紧张稳步展开,有望进一步紧缩金融环境。在接下来的几年中,我们的资产负债表将显著缩减。

我们上个月的会议上,FOMC投票决定将联邦基金利率提升至了1.50%-1.75%。这也是表明我们紧缩政策的有一举动。FOMC的渐进紧缩路径有助于经济体更为强劲。

接下来的几年间,我们将持续以2%为通胀目标,以及维持强劲的劳动力市场以支撑经济扩张。正如我说的,我与我的FOMC同事认为,经济会持续强劲,渐进加息是达到这些目标的最佳路径。如果加息太慢,则有可能面临需要突然紧缩的窘境,这对经济扩张是有害的。而加息太快也会导致通胀长期低于2%的目标。我们的渐进加息策略正在于平衡这两个风险。

当然,我们对于合适的货币政策的观点在接下来的几个月甚至几年间都将根据经济数据和展望而调整。我们主要目标仍会不变:增加更多的就业和稳定通胀水平。

作者:澎湃新闻 蒋梦莹

April 06, 2018

The Outlook for the U.S. Economy

Chairman Jerome H. Powell

At The Economic Club of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

Jerome H. Powell, the Federal Reserve chairman, addressing the Economic Club of Chicago on Friday. He emphasized the economy’s strength, touching on the looming threat of a trade war only in a question-and-answer session. Lyndon French for The New York Times

For more than 90 years, the Economic Club of Chicago has provided a valued forum for current and future leaders to discuss issues of vital interest to this city and our nation. I am honored to have the opportunity to speak to you here today.

At the Federal Reserve, we seek to foster a strong economy for the benefit of individuals, families, and businesses throughout our country. In pursuit of that overarching objective, the Congress has assigned us the goals of achieving maximum employment and stable prices, known as the dual mandate. Today I will review recent economic developments, focusing on the labor market and inflation, and then touch briefly on longer-term growth prospects. I will finish with a discussion of monetary policy.

Recent Developments and the State of the Economy

After what at times has been a slow recovery from the financial crisis and the Great Recession, growth has picked up. Unemployment has fallen from 10 percent at its peak in October 2009 to 4.1 percent, the lowest level in nearly two decades (figure 1). Seventeen million jobs have been created in this expansion, and the monthly pace of job growth remains more than sufficient to employ new entrants to the labor force (figure 2). The labor market has been strong, and my colleagues and I on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) expect it to remain strong. Inflation has continued to run below the FOMC's 2 percent objective but we expect it to move up in coming months and to stabilize around 2 percent over the medium term.

Beyond the labor market, there are other signs of economic strength. Steady income gains, rising household wealth, and elevated consumer confidence continue to support consumer spending, which accounts for about two thirds of economic output. Business investment improved markedly last year following two subpar years, and both business surveys and profit expectations point to further gains ahead. Fiscal stimulus and continued accommodative financial conditions are supporting both household spending and business investment, while strong global growth has boosted U.S. exports.

As many of you know, each quarter FOMC participants--the members of the Board of Governors and the presidents of the Reserve Banks--submit their individual projections for growth, unemployment, and inflation, as well as their forecasts of the appropriate path of the federal funds rate, which the Committee uses as the primary tool of monetary policy. These individual projections are compiled and published in the Summary of Economic Projections, or SEP. FOMC participants submitted their most recent forecasts three weeks ago, and those forecasts show a strengthening in the medium-term economic outlook (table 1). As you can see, participants generally raised their forecasts for growth in inflation-adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) and lowered their forecasts for unemployment. In addition, many participants expressed increased confidence that inflation would move up toward our 2 percent target. The FOMC sees the risks to the economic outlook as roughly balanced.

The State of the Labor Market

As I mentioned, the headline unemployment rate has declined to levels not seen since 2000. The median projection in the March SEP calls for unemployment to fall well below 4 percent for a sustained period, something that has not happened since the late 1960s. This strong labor market forecast has important implications for the fulfillment of both sides of the dual mandate, and thus for the path of monetary policy. So I will spend a few minutes exploring the state of the job market in some detail.

A good place to begin is with the term "maximum employment," which the Committee takes to mean the highest utilization of labor resources that is sustainable over time. In the long run, the level of maximum employment is not determined by monetary policy, but rather by factors affecting the structure and dynamics of the labor market.1 Also, the level of maximum employment is not directly measureable, and it changes over time. Real-time estimates of maximum employment are highly uncertain.2 Recognizing this uncertainty, the FOMC does not set a fixed goal for maximum employment. Instead, we look at a wide range of indicators to assess how close the economy is to maximum employment.

The headline unemployment rate is arguably the best single indicator of labor market conditions. In addition, it is widely known and updated each month. As I noted, the unemployment rate is currently at 4.1 percent, which is a bit below the FOMC's median estimate of the longer-run normal rate of unemployment. However, the unemployment rate does not paint a complete picture. For example, to be counted in the official measure as unemployed, a person must have actively looked for a job in the past four weeks.3 People who have not looked for work as recently are counted not as unemployed, but as out of the labor force, even though some of them actually want a job and are available to work. Others working part time may want a full-time job. And still others who say that they do not want a job right now might be pulled into the job market if the right opportunity came along. So, in judging tightness in the labor market, we also look at a range of other statistics, including alternative measures of unemployment, as well as measures of vacancies and job flows, surveys of households' and businesses' perceptions of the job market, and, of course, data on wages and prices.

Figure 3 shows the headline unemployment rate and two broader measures of unemployment, known as U-5 and U-6.4 U-5 includes the unemployed plus people who say they want a job and have looked for one in the past year (though not in the past four weeks). U-6 includes all those counted in U-5 plus people who are working part time but would like full-time work. Like the headline unemployment rate, both U-5 and U-6 have declined significantly in recent years. They are now at levels seen before the financial crisis, though not quite as low as they were in 1999 to 2000, a period of very tight job market conditions.

The left panel of the next chart shows that employers are having about as much difficulty now attracting qualified workers as they did 20 years ago (figure 4). Likewise, the job vacancy rate, shown on the right, is close to its all-time high, as is the average number of weeks it takes to fill a job opening.5 Households also are increasingly reporting that jobs are plentiful (figure 5), which is consistent with the high level of job postings reported by firms. In addition, the proportion of workers quitting their jobs is high, suggesting that workers are being hired away from their current employers and that others are confident enough about their prospects to leave jobs voluntarily--even before they have landed their next job.

While the data I have discussed thus far do point to a tight labor market, other data are less definitive. The labor force participation rate, which measures the percentage of working age individuals who are either working or actively looking for a job, has remained steady for about four years (figure 6). This flat performance is actually a sign of improvement, since increased retirements as our population ages have been putting downward pressure on participation and will continue to do so. However, the participation rate of prime-age workers (those between the ages of 25 and 54) has not recovered fully to its pre-recession level, suggesting that there might still be room to pull more people into the labor force (figure 7). Indeed, the strong job market does appear to be drawing back some people who have been out of the labor force for a significant time. For example, the percentage of adults returning to the labor force after previously reporting that they were not working because of a disability has increased over the past couple of years, and anecdotal reports indicate that employers are increasingly willing to take on and train workers they would not have considered in the past.6

Wage growth has also remained moderate, though it has picked up compared with its pace in the early part of this recovery (figure 8). Weak productivity growth is an important reason why we have not seen larger wage gains in recent years. At the same time, the absence of a sharper acceleration in wages suggests that the labor market is not excessively tight. I will be looking for an additional pickup in wage growth as the labor market strengthens further.

Taking all of these measures of labor utilization on board, what can we say about the state of the labor market relative to our statutory goal of maximum employment? While uncertainty around the long run level of these indicators is substantial, many of them suggest a labor market that is in the neighborhood of maximum employment. A few other measures continue to suggest some remaining slack. Assessments of the maximum level of employment are uncertain, however, and subject to revision. As we seek the highest sustainable utilization of labor resources, the Committee will be guided by incoming data across all of these measures.

Inflation

That brings me to inflation--the other leg of our dual mandate. The substantial improvement in the labor market has been accompanied by low inflation. Indeed, inflation has continued to run below our 2 percent longer-run objective (figure 9). Consumer prices, as measured by the price index for personal consumption expenditures, increased 1.8 percent over the 12 months ending in February. The core price index, which excludes the prices of energy and food and is typically a better indicator of future inflation, rose 1.6 percent over the same period. In fact, both of these indexes have been below 2 percent consistently for the past half-dozen years. This persistent shortfall in inflation from our target has led some to question the traditional relationship between inflation and the unemployment rate, also known as the Phillips curve. Given how low the unemployment rate is, why aren't we seeing higher inflation now?

As those of you who carefully read the minutes of each FOMC meeting are aware--and I know there are some of you out there--we had a thorough discussion of inflation dynamics at our January meeting. Almost all of the participants in that discussion thought that the Phillips curve remained a useful basis for understanding inflation. They also acknowledged, however, that the link between labor market tightness and changes in inflation has become weaker and more difficult to estimate, reflecting in part the extended period of low and stable inflation in the United States and in other advanced economies. Participants also noted that other factors, including inflation expectations and transitory changes in energy and import prices, can affect inflation.

My view is that the data continue to show a relationship between the overall state of the labor market and the change in inflation over time. That connection has weakened over the past couple of decades, but it still persists, and I believe it continues to be meaningful for monetary policy. Much of the shortfall in inflation in recent years is well explained by high unemployment during the early years of the recovery and by falling energy prices and the rise in the dollar in 2015 and 2016. But the decline in inflation last year, as labor market conditions improved significantly, was a bit of a surprise. The 2017 shortfall from our 2 percent goal appears to reflect, at least partly, some unusual price declines, such as for mobile phone plans, that occurred nearly a year ago. In fact, monthly inflation readings have been firmer over the past several months, and the 12-month change should move up notably this spring as last spring's soft readings drop out of the 12-month calculation. Consistent with this view, the median of FOMC participants' projections in our March survey shows inflation moving up to 1.9 percent this year and to 2 percent in 2019.

Longer-Run Challenges

Although job creation is strong and unemployment is low, the U.S. economy continues to face some important longer-run challenges. GDP growth has averaged just over 2 percent per year in the current economic expansion, much slower than in previous expansions. Even the higher growth seen in recent quarters remains below the trend before the crisis. Nonetheless, the unemployment rate has come down 6 percentage points during the current expansion, suggesting that the trend growth necessary to keep the unemployment rate unchanged has shifted down materially. The median of FOMC participants' projections of this longer-run trend growth rate is 1.8 percent. The latest estimate from the Blue-Chip consensus of private forecasters is about 2 percent.7

To unpack this discussion a little further, we can think of output growth as composed of increases in hours worked and in output per hour, also known as productivity growth. Here, a comparison with the 2001-to-2007 expansion is informative. Output growth in that earlier expansion averaged nearly 3 percent per year, well above the pace in the current expansion. Despite the faster output growth, however, average job growth in the early 2000s was 1/2 percentage point per year weaker than in the current expansion. The difference, of course, is productivity, which grew at more than twice the pace in the early 2000s than it has in recent years.

Taking a longer view, the average pace of labor productivity growth since 2010 is the slowest since World War II and about one-fourth of the average postwar rate (figure 10). Moreover, the productivity growth slowdown seems to be global and is evident even in countries that were little affected by the financial crisis (figure 11). This observation suggests that factors specific to the United States are probably not the main drivers.

As shown in figure 12, labor productivity growth can be broken down into the contributions from business investment (or capital deepening), changes in the skills and work experience of the workforce, and a residual component that is attributed to other factors such as technological change and efficiency gains (usually lumped together under the term total factor or multifactor productivity).

In the United States and in many other countries, some of the slowdown in labor productivity growth can be traced to weak investment after the crisis. Investment has picked up recently in the United States, however, which suggests that capital deepening may pick up as well. The other big contributor to the slowdown has been in total factor productivity growth. The outlook for this dimension of productivity is considerably more uncertain. Total factor productivity growth is notoriously difficult to predict, and there are sharply different views on where it might be heading. Some argue that the productivity gains from the information technology revolution are largely behind us, and that more-recent technological innovations have less potential to boost productivity.8 Others argue that a well-documented decline in measures of business dynamism--such as the number of start-ups, the closure of less-productive businesses, and the rates at which workers quit their jobs and move around the country to take a new job--has held back productivity growth, in part by slowing the movement of capital and labor toward their most productive uses.9

New technological breakthroughs in many areas--robotics, biotech, and artificial intelligence to name just a few--have led others to take a more optimistic view.10 They point to substantial productivity gains from innovation in areas such as energy production and e-commerce. In addition, the optimists point out that advances in technology often take decades to work their way into the economy before their ultimate effects on productivity are felt. That delay has been observed even for game-changing innovations like the steam engine and electrification, which ultimately produced broad increases in productivity and living standards. In this view, we just need to be patient for new technologies to diffuse through the economy. Only time will tell who has the better view??the record provides little basis to believe that we can accurately forecast the rate of increase in productivity.

The other principal contributor to output growth is hours worked. Hours growth, in turn, is largely determined by growth in the labor force, which has averaged just 1/2 percent per year since 2010, well below the average in previous decades (figure 13). One reason for slower growth of the labor force is that baby boomers are aging and retiring, and that trend will continue. But another reason is that labor force participation of people between the ages of 25 and 54--prime-age individuals--declined from 2010 to 2015 and remains low. Indeed, the participation rate for prime-age men has been falling for more than 50 years, while women's participation in this age group rose through the 1990s but then turned downward, and it has fallen for the past 20 years.

These trends in participation have been more pronounced in the United States than in other advanced economies. In 1990, the United States had relatively high participation rates for prime-age women relative to other countries and was in the midrange of advanced economies for prime-age men. However, we now stand at the low end of participation for both men and women in this age group--just above Italy, but well below Germany, France, and Spain (figure 14).

There is no consensus about the reasons for the long-term decline in prime-age participation rates, and a variety of factors could have played a role.11 For example, while automation and globalization have contributed positively to overall domestic production and growth, adjustment to these developments has resulted in dislocations of many workers without college degrees and those employed in manufacturing. In addition, factors such as the increase in disability rolls in recent decades and the opioid crisis may have reduced the supply of prime-age workers. Given that the declines have been larger here than in other countries, it seems likely that factors specific to the United States have played an important role. As I noted earlier, the strong economy may continue to pull some prime-age individuals back into the labor force and encourage others not to drop out. Research suggests that structurally-oriented measures--for example, improving education or fighting the opioid crisis--also will help raise labor force participation in this age group.12

To summarize this discussion, some of the factors weighing on longer-term growth are likely to be persistent, particularly the slowing in growth of the workforce. Others are hard to predict, such as productivity. But as a nation, we are not bystanders. We can put policies in place that will support labor force participation and give us the best chance to achieve broad and sustained increases in productivity, and thus in living standards. These policies are mostly outside the toolkit of the Federal Reserve, such as those that support investment in education and workers' skills, business investment and research and development, and investment in infrastructure.

Monetary Policy

Let me turn now to monetary policy. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the FOMC went to extraordinary lengths to promote the recovery, support job growth, and prevent inflation from falling too low. As the recovery advanced, it became appropriate to begin reducing monetary policy support. Since monetary policy affects the economy with a lag, waiting until inflation and employment hit our goals before reducing policy support could have led to a rise in inflation to unwelcome levels. In such circumstances, monetary policy might need to tighten abruptly, which could disrupt the economy or even trigger a recession.

As a result, to sustain the expansion, the FOMC adopted a gradual approach to reducing monetary policy support. We began in December 2015 by raising our target for the federal funds rate for the first time in nearly a decade. Since then, with the economy improving but inflation still below target and some slack remaining, the Committee has continued to gradually raise interest rates. This patient approach also reduced the risk that an unforeseen blow to the economy might push the federal funds rate back near zero??its effective lower bound--thus limiting our ability to provide appropriate monetary accommodation.

In addition, after careful planning and public communication, last October the FOMC began to gradually and predictably reduce the size of the Fed's balance sheet. Reducing our securities holdings is another way to move the stance of monetary policy toward neutral. The balance sheet reduction process is going smoothly and is expected to contribute over time to a gradual tightening of financial conditions. Over the next few years, the size of our balance sheet is expected to shrink significantly.

At our meeting last month, the FOMC raised the target range for the federal funds rate by 1/4 percentage point, bringing it to 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 percent. This decision marked another step in the ongoing process of gradually scaling back monetary policy accommodation. The FOMC's patient approach has paid dividends and contributed to the strong economy we have today.

Over the next few years, we will continue to aim for 2 percent inflation and for a sustained economic expansion with a strong labor market. As I mentioned, my FOMC colleagues and I believe that, as long as the economy continues broadly on its current path, further gradual increases in the federal funds rate will best promote these goals. It remains the case that raising rates too slowly would make it necessary for monetary policy to tighten abruptly down the road, which could jeopardize the economic expansion. But raising rates too quickly would increase the risk that inflation would remain persistently below our 2 percent objective. Our path of gradual rate increases is intended to balance these two risks.

Of course, our views about appropriate monetary policy in the months and years ahead will be informed by incoming economic data and the evolving outlook. If the outlook changes, so too will monetary policy. Our overarching objective will remain the same: fostering a strong economy for all Americans--one that provides plentiful jobs and low and stable inflation.

1. See the FOMC's Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, amended effective January 30, 2018, available on the Board's website athttps://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/FOMC_LongerRunGoals.pdf. Return to text

2. This fundamental uncertainty has been extensively studied, particularly with respect to the most commonly used measure of full employment--the so-called natural rate of unemployment. The authors of one well-regarded study concluded that even when using sophisticated statistical techniques, the natural rate of unemployment could be as much as 1-1/2 percentage points above or below their point estimate. See Douglas Staiger, James H. Stock, and Mark W. Watson (1997), "How Precise Are Estimates of the Natural Rate of Unemployment? (PDF)" chapter 5 in Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, eds., Reducing Inflation: Motivation and Strategy(Chicago: University of Chicago Press), pp. 195-246. Return to text

3. Individuals expecting to be recalled from a temporary layoff are also counted as unemployed whether or not they are actively looking for work. Return to text

4. The official unemployment rate is known as U-3. Return to text

5. These data are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS, and start in 2000. Return to text

6. For disability transition rates, see Ernie Tedeschi (2018), "Will Employment Keep Growing? Disabled Workers Offer a Clue," The Upshot, New York Times, March 15. Return to text

7. Wolters Kluwer (2018), Blue Chip Economic Indicators, vol. 43, no. 3 (March 10). Return to text

8. See, for example, Robert J. Gordon (2016), The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press). Return to text

9. See, for example, Ryan A. Decker, John Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda (2016), "Declining Business Dynamism: What We Know and the Way Forward," American Economic Review, vol. 106 (May), pp. 203?07. Return to text

10. See, for example, Erik Brynjolfsson, Daniel Rock, and Chad Syverson (2017), "Artificial Intelligence and the Modern Productivity Paradox: A Clash of Expectations and Statistics," NBER Working Paper Series 24001 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, November). Return to text

11. See, for example, Katharine G. Abraham and Melissa S. Kearney (2018), "Explaining the Decline in the U.S. Employment-to-Population Ratio: A Review of the Evidence," NBER Working Paper Series 24333 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, February). Return to text

12. See Alan B. Krueger (2017), "Where Have All the Workers Gone? An Inquiry into the Decline of the U.S. Labor Force Participation Rate," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, pp. 1-87. Return to text