笨狼发牢骚

发发牢骚,解解闷,消消愁【海洋资源】

2014

2015

光伏效率最新研究

Are Americans Working Less Than the Rest of the World?

| Location | Avg Hours Worked Ann | Hours Rank | Labor-Force Participation | Participation-Rate Rank | 2013 GDP Change | GDP Rank |

| Mexico | 2,237 | 1 | 60.50% | 19 | 1.40% | 21 |

| Korea | 2,163 | 2 | 61.50% | 16 | 2.90% | 7 |

| Greece | 2,060 | 3 | 52.00% | 36 | -3.90% | 38 |

| Chile | 2,015 | 4 | 59.60% | 23 | 4.20% | 2 |

| Russia | 1,980 | 5 | 68.50% | 4 | 1.30% | 22 |

| Latvia | 1,928 | 6 | 59.40% | 24 | 4.20% | 1 |

| Poland | 1,918 | 7 | 55.90% | 34 | 1.70% | 14 |

| Hungary | 1,880 | 8 | 57.00% | 32 | 1.50% | 18 |

| Israel | 1,867 | 9 | 63.70% | 12 | 3.40% | 5 |

| Estonia | 1,866 | 10 | 68.30% | 6 | 1.60% | 16 |

| Portugal | 1,852 | 11 | 59.30% | 27 | -1.60% | 36 |

| Iceland | 1,846 | 12 | 81.40% | 1 | 3.60% | 4 |

| Lithuania | 1,839 | 13 | 58.00% | 30 | 3.30% | 6 |

| Turkey | 1,832 | 14 | 50.80% | 37 | 4.20% | 3 |

| Ireland | 1,815 | 15 | 60.50% | 18 | 0.20% | 28 |

| United States | 1,788 | 16 | 63.20% | 13 | 2.20% | 9 |

| Slovak Republic | 1,772 | 17 | 59.30% | 28 | 1.40% | 19 |

| Average of OEDC Members | 1,770 | 18 | 60.10% | 21 | 1.40% | 20 |

| Czech Republic | 1,763 | 19 | 59.30% | 29 | -0.50% | 32 |

| New Zealand | 1,752 | 20 | 68.20% | 7 | 2.20% | 8 |

| Japan | 1,734 | 21 | 59.30% | 26 | 1.60% | 17 |

| Italy | 1,733 | 22 | 49.30% | 38 | -1.70% | 37 |

| Canada | 1,708 | 23 | 66.50% | 8 | 2.00% | 11 |

| Spain | 1,699 | 24 | 60.00% | 22 | -1.20% | 34 |

| United Kingdom | 1,669 | 25 | 63.10% | 14 | 1.70% | 15 |

| Australia | 1,663 | 26 | 64.90% | 11 | 2.10% | 10 |

| Luxembourg | 1,649 | 27 | 59.40% | 25 | 2.00% | 12 |

| Finland | 1,643 | 28 | 65.50% | 9 | -1.30% | 35 |

| Austria | 1,629 | 29 | 60.90% | 17 | 0.20% | 27 |

| Sweden | 1,607 | 30 | 71.50% | 2 | 1.30% | 23 |

| Switzerland | 1,576 | 31 | 68.30% | 5 | 1.90% | 13 |

| Belgium | 1,576 | 32 | 53.60% | 35 | 0.30% | 26 |

| Slovenia | 1,550 | 33 | 57.20% | 31 | -1.00% | 33 |

| France | 1,489 | 34 | 56.50% | 33 | 0.70% | 25 |

| Denmark | 1,438 | 35 | 62.40% | 15 | -0.50% | 30 |

| Netherlands | 1,421 | 36 | 65.20% | 10 | -0.50% | 31 |

| Norway | 1,408 | 37 | 71.20% | 3 | 0.70% | 24 |

| Germany | 1,363 | 38 | 60.30% | 20 | 0.10% | 29 |

【《缅甸】

外媒热议昂山素季率团访华(杂)

姚颖、张伟玉:《甸街头巷尾,人们怎么看昂山素季访华

【英国独立报》(此报道被中文媒体瞎转)Burma election: China tries to woo opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi ahead of poll

《路透社》Irritated with Myanmar, China to woo opposition leader Suu Kyi

【观察网】一张图看懂中国在缅甸的利益

《国际网》2013.06.17

方筠娴:缅甸对华外交政策受地缘政治考量的影响有多大?

(作者为英国切特豪斯中学(Charterhouse School)高三学生)

李晨阳:政治转型以来的中缅(探索不同规模国家关系模式)

《时代尖兵的博客》2011

“友邦”缅甸为何突然猛抽中国耳光?

中缅关系,我们该如何扭转危局?

《金融时报中文网》2013.06.19

分析:中缅关系日渐疏远

一名缅甸部长的顾问说:“我们对中国人的帮助表示‘非常感谢’,然后请他们离开。”

【疲敝的冷战】

《纽约时报》美国拟在东欧部署重武器,威慑俄罗斯(英文)

路透社转载

图片

《Pew》

Key findings from our poll on the Russia-Ukraine conflict

《CNN》Obama: Europe will continue sanctions on Russia

《RT》'US drawing Europe into crusade against Russia, against our interests' – ex-French PM

《一财》

中国成全球综艺模式竞技场 本土原创在哪儿?

《钛媒体》

外国版权都被买光了,未来中国综艺模式怎么走?

《一财》

高通人事连环变动:王翔投奔小米 孟樸回归

《钛媒体》

高通中国掌门人王翔加盟小米:小米补“芯”又胜一筹

高通案蝴蝶效应:小米距离专利围剿有多远

高通案背后的中美知识产权博弈

高通反垄断整改变数多 企业哭诉“

国产手机将打专利内战?谁将会被围剿

参见。

辛一山,载于《草根网》

浅论道家“虚无”与佛教“空”观的区别

无神论文化语境下,由于理想缺失,众多民众开始新的追求,道家文化和佛教思想无疑成为了被追逐的对象。

由于开始的无神论,无立场使得很多中国人对于佛教和道家思想都感兴趣,都有学习的意愿。在学习中,民众对于道家的“虚无”和佛家的“空”难以精准认识。以至于有些人说虚和空是一样的,有一致性,有些人则说有区别,但具体有什么区别则说不清。所以本文的主旨是解释说清虚无与空的区别,以使得这两个关键的概念明晰,让民众清楚道家与佛教的基本区别。

首先,在世界观的宏观层面上看道家与佛家有一致性。道家认为,宇宙世界的本原是太极是虚无,佛家认为宇宙世界的本原是空,一切皆空。表面上两者的世界观论述是一致的。但由于佛道两家不同的出发点和目的性导致了“虚无”与“空”在观念上出现了很大的不同。

佛教是婆罗门教衍生出来的,其本原是婆罗门教。婆罗门教认为世界的本质是梵,梵我为一,梵是一切的终极。而且世界的一切都是依照本原梵进行轮回的。婆罗门教“梵”的轮回流转理论中,出现了同一“梵”在不同人身上呈现出来的不同性矛盾。释迦牟尼觉悟到世界的本质是空,无论是大的宇宙或者是人,还是细小的物体其本质都是空。现代物理学知识也让我们知道,即使到了院子层面上,空的定义是正确的。因为分子、原子等百分之90几是空的。释迦牟尼指出人要觉悟摆脱轮回的苦痛只有通过“空”这一途径。因此“空”成为佛家弟子修炼觉悟的方法。由于有对世界本原这样的认识,佛家认为“诸行无常、诸法无我”。释迦牟尼觉悟到跳出轮回苦海的方法就是无我。因此无欲无求、无我的修炼方法成为佛家的根本修炼法。在这其中释迦牟尼将婆罗门教定义世界本原“梵”发展完善为“空”。佛教的“空”观,空性、无我等从目的性来讲是为了完成觉悟的个人修炼方法,是从本体个性化来体悟世界的本质。

道家的“虚无”则是出自于对世界的认识。道家认为世界的本原是太极,是虚无。太极学说源于易的阴阳文化,我国传统的阴阳文化将世界上所有的事物都分为阴阳,阴阳相互转变、相互影响。阴阳是由太极衍生出来的,这只是一个理论上的说法,无碍于实际运用,因此历史上很少有人专项考证“太极”。道家的方法论是思想重视实用,因此阴阳平衡被运用于各式事物之中。“虚无”虽是太极定义导引出来的,但这个方法也是道家个人强身壮体的实用方法。道家认为人的寿命有限,打破有限生命极限的方法是学习天地长久的方法。天地长久的方法就是不依赖外界的条件而生存。因此道家认为采用“虚空”纳气的方法可以摆脱依赖食物维持生命这样的方式,有利于长生不老。鬼谷子说:“命之机在于气,气之机在于心”延续生命在于气,锻炼意识的自我控制能力就是养生。“虚无”就是练气的基本方法。入静是导致虚无的方法,这有点类似于物理上追求达致-273k这样的状态,当到达绝对零度当然一切都静止归于根本。就是所谓的”致虚极、守静笃“。道家的”虚无观是实用性的,他源于实际上求解问题的需要,也源于对规律性的不懈求解。所以从方法论本原来看,道家的“虚无”观来源与长期对客观世界观察的归纳,而佛家的“空”观则来源与本体的“自悟”和经验的传授。

道家和佛家的思想其根本是无神论,而现在很多的佛教和道教心中都将其迷信化、神秘化。事物本无所谓对错,观念的不同只是观察角度和出发点的不同,还有目的性的不同也会导致出现类似的观念演化出很不同的结果,佛教的“空”和道家的“虚无”就是一例。言犹未尽之处请方家见谅。

《The European Financial Review》

A Different Global Power? Understanding China’s Role in the Developing World

June 19, 2014 • China & The World Series, Editor's choice, Emerging & Frontier Markets, Global Focus, WORLD

By Xiangming Chen & Ivan Su

China is now the largest trading nation in the world, with strong ties to Africa, Latin and America and the Middle East. This once impoverished and isolated nation has lifted several hundred millions of its own people out of poverty and is now reshaping the developing world. This article looks at China’s involvement in four developing regions to assess China’s influence as a rising global power.

The China where the first author grew up through college in the early 1980s was the largest and one of the poorest developing countries. The China where the second author left to attend high school in the United States was about to pass Japan to become the world’s second largest economy, in 2010. Over the past three decades, China has lifted over 500 million of its people out of poverty. Globally, China has just surpassed the United States to become the largest trading nation in the world and is expected to soon overtake the latter as the world’s largest economy (in terms of purchasing power parity or PPP). More importantly regarding the focus of this essay, China is now the largest trader and investor in Africa, with its footprints spreading and seeping into all corners of the developing world.

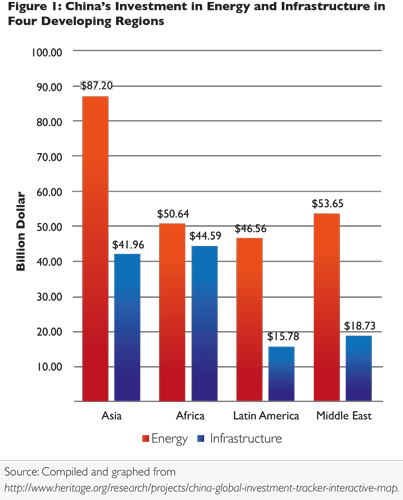

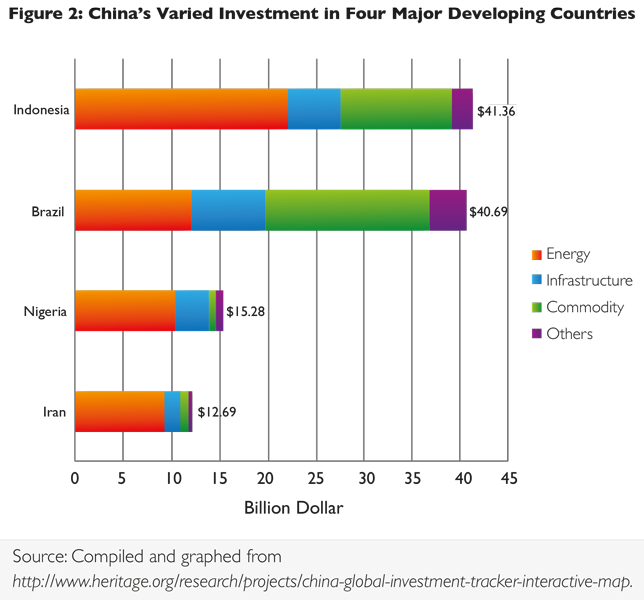

How did the once impoverished and isolated “Third World” country become a powerful force in shaping a new developing world in the 21st century? What are the positive vs. negative consequences of China’s inroads into developing countries by exporting its urbanism to Africa, for example? These questions highlight China’s global impact that matters a great deal to the everyday life of millions of poor people in developing countries. In this essay, following China’s global footprints in four developing regions, we offer a broad comparison of both the different and consistent economic impacts of China within and across these regions.1 Figure 1 shows China’s investment in energy and infrastructure in the four regions, while Figure 2 breaks China’s investment into four specific sectors of one major country in each of the four regions. Guided by these comparative data and focusing on four developing regions, we present a broad picture of China’s widespread but mixed role in developing countries, thus offering a preliminary assessment of whether China’s influence as a rising global power may differ from the traditional or established Western powers in how they approach the developing world.

Over the past three decades, China has lifted over 500 million of its people out of poverty.

China in Asia: Exerting Neighbouring Influences

Back in the last decades of the 20th century, the drivers and role models for development in Asia and beyond were the “Four Tigers”: Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. The onset of the 21st century began to position China toward the epicentre of the Asian economy, with its influence spreading across the continent through more trade, outward investment, and other outgoing initiatives such as cross-border infrastructure development.

In Southeast Asia, China has been trying to integrate with the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), which consists of China’s Yunnan Province, Guangxi Autonomous Region, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam. “China’s trade with each of the GMS countries has grown since 1990, most rapidly since 2000.”2 In addition to increasing trade, China exerts strong influence on the GMS through various development projects. In Myanmar, China has reached a $20 billion agreement to construct an 800-kilometre rail link between Myanmar’s Chinese border and its western coast.3 In addition to investing in infrastructure, China is also helping its neighbors to generate energy. Since 2005, China has invested over $87 billion in the energy sector across Asia, and about one quarter of these investments went to Malaysia. In 2010, an $11 billion energy deal signed between China’s State Grid Corporation and Malaysia Development Company included four hydroelectric mega-dams that are capable of generating up to 28,000 megawatts of power, an aluminium-smelting plant, exploitation of coal mines containing 1.5 billion metric tons of coal, and a 40 billion-cubic-feet natural gas development project. “With Malaysia reeling from an exodus of capital over the past two years, the projects have strong support at the state and federal levels. Officials hope the plan will attract foreign investment to the region.”4

China’s investment in Asia is not limited to Southeast Asia, as countries in South and Central Asia have also been affected by China’s direct investment. In 2013, China established a strong foothold in South Asia when it took over the upgrading and operation of Pakistan’s Gwadar Port from Singapore. The Gwadar project serves China’s “Go West” policy while allowing Pakistan to “look east.” China is building a road from Gwadar all the way north to Kashgar, the westernmost large city in Xinjiang. At the same time, Pakistan and China have also planned to connect the port via the Indus Highway, which will provide China with a land-based supply of oil from Central Asia. Given Gwadar’s geographical location, Gwadar cuts China’s distance from the Persian Gulf, from which China gets 60% of its oil, by thousands of kilometres.5

Since 2005, China has invested over $87 billion in the energy sector across Asia, and about one quarter of these investments went to Malaysia.

Compared to the other energy projects sponsored by China, the Central Asian vector of China’s energy policy has become more important due to the region’s abundance of oil and natural gas. While China sees Kazakhstan’s energy supply a key to its “Go West” program, Kazakhstan has used Sino-Kazakh cooperation to balance against Russia’s influence in its energy sector. China is also constructing a 1,800-kilometre natural gas pipeline from one of the world’s largest natural gas exporter, Turkmenistan, which benefits from doubling its energy supply to China and circumventing its biggest competitor – Russia. Beijing wins by securing new gas supplies and thus enlarging its already hefty investment in energy projects in Asia (see Figure 1).

China in Africa: Reaching Maximum Impact

Through increasing trade and investment, China’s growing presence has reshaped the landscape in Africa. While negligible two decades ago, China-Africa trade reached $200 billion in 2013, which makes China Africa’s largest trading partner today. With only limited investment in Africa before the 2000s, China’s cumulative investment in Africa exceeded $150 billion by the beginning of 2014. Of these investments, close to $100 billion has gone into energy and infrastructure projects.6

China’s unprecedented economic growth requires an increasing amount of oil to sustain it. In 2012, close to one-third of China’s total oil imports came from Africa, and China is looking to expand its energy presence in Africa. Nigeria has received the most Chinese direct investment over the past decade. While many Western energy firms are reluctant, China reached a $10 billion hydrocarbon deal with Nigeria at the beginning of 2014 (see Photo 1). In addition to exploiting crude oil and natural gas, China has been involved in constructing an additional refinery in Baro, Nigeria.7 Although critics have attributed China’s heavy footprint in Africa’s energy sector to its energy and resource demand back home, evidence suggests otherwise. China Africa Sunlight Energy Ltd. recently invested $2.1 billion in developing a 2,100-megawatt plant to help ease electricity shortages in Zimbabwe, which is only capable of generating 1,320 megawatts against a demand of 2,200 megawatts of electricity. “China Africa Sunlight Energy is looking at the possibility of pumping gas to the port city of Beira in neighbouring Mozambique, using an idle pipeline that the National Oil Co. of Zimbabwe once used to bring fuel into the country.”8 This power plant is expected to produce 300 megawatts by mid-2015, and the number is looking to double by the end of the year. While much of the media attention has focused on China’s investment in Africa’s energy sector, China is reshaping Africa’s landscape through large-scale infrastructure development.

Since 2005, China has invested more in Africa’s infrastructure than in any other part of the developing world. More than $44 billion has been spent to build roads, airports, and housing that are essential to the continent’s economic development. In Angola, China is helping the country’s reconstruction effort after the devastating civil war. One of China’s major investments in Angola is the rebuilding of the Benguela Railway, “an 840-mile transcontinental railway that links the Atlantic port of Lobito in Angola with rail networks in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia. The project is expected to cost $300 million, and it will provide a much-needed cheap outlet for Congolese and Zambia copper, tin and coltan.”9 In Nigeria, China is helping to build Africa’s largest free trade zone in its commercial capital, Lagos. “A total of 16,500 hectares of land bordered by the Atlantic Ocean and the Lagos and Lekki lagoons has been earmarked for the whole free zone, which will include a deep-water sea port and a new international airport in close proximity.”10 The Lekki Free Trade Zone is aiming to cut down the country’s reliance on imports, and it will cost $5 billion to complete the first phrase of the project, which will cover 3,000 hectares of land. The construction will also include roads, power plants, and water plants. This evidence reinforces China’s substantial investment in building Africa’s infrastructure relative to the energy sector in comparison with the other developing regions (see Figure 2).

However, concerns arise on whether Africa is too dependent on China as results of “high commodity prices and investment inflows.”11 With China-Africa trade looking to hit $280 billion by 2015, some worry that African economies depend too much on China. Some urge African countries to diversify their economies and decrease their dependence on China. There are also calls for China to focus more on human rights and community engagement. As such a dominant investor in some African countries including those with an authoritarian government like Zimbabwe, China struggles to balance between the return on its huge investment, helping local development and living up to international norms of engagement.

With only limited investment in Africa before the 2000s, China’s cumulative investment in Africa exceeded $150 billion by the beginning of 2014.

China in Latin America: Extending the Reach

Ever since the 1960s, China has been providing limited development assistance to a small number of Latin American countries such as Chile. Fast-forward to the 21st century, China has considerably expanded its economic ties with Latin America through greater trade and more diverse investment.

“Trade between China and Latin American countries has grown exponentially over the past decade. Although Sino-Latin American trade continues to remain a relatively small share of their respective global trade, growth has exceeded many expectations. From 2000 to 2009, annual trade between China and Latin American countries grew more than 1,200%, from $10 billion to $130 billion, according to the United Nations statistics.”12 In 2012, Latin America accounted for 13% of China’s total outbound investment – about $11.4 billion, a significant increase from the $120 million of 2004.

In 2012, Latin America accounted for 13% of China’s total outbound investment – about $11.4 billion, a significant increase from the $120 million of 2004.

Like in Asia and Africa, China has favoured the energy sector in Latin America (see Figure 1), targeting Venezuela for its oil and Brazil for its hydropower. Of China’s $100 billion investment in Latin America since 2005, more than half has been energy and infrastructure related. In 2010, China’s State Grid announced a $1 billion buyout of seven Brazilian power transmission companies. Two years later, in 2012, China’s State Grid was chosen by the Brazilian government to build a $440 million power-transmission project. And at the end of 2013, China’s State Grid led a group to win the rights building a $21 billion hydropower plant in Brazil. Set to become the world’s third-largest hydropower plant and take around 46 months to complete, it will also create a 2,092 km hydropower transmission line and two energy converter stations that will be able to take energy from the State of Pará, along the Xingu River in the Amazon Basin, to Brazil’s Southeast region, with a planned capacity of 11,233 megawatts. Brazil’s economic acceleration in the past decade led to a surge in the country’s energy demand. Given Brazil’s geographical endowment, as much as 80% of its total energy comes from hydropower generation.13 With power generation operating close to the limit, Brazil is urgently constructing more power plants using the Amazon’s abundant hydro resources and transmitting it to its Southeast region, especially Rio de Janeiro where much more energy is needed in light of the upcoming World Cup and Summer Olympics in 2016. To do so, Brazil has turned to China for its expertise and experience in building long-distance power transmission towers or the so-called electricity pylons (see Photo 2).

Besides its growing economic presence in Latin America, China has made some cultural inroads as well. Since 2012, China has opened 32 new Confucius Institutes all over Latin America, a Chinese foreign ministry deputy announced. Hotels in the region have begun to prepare for the increasing number of Chinese tourists by making the menus available in Mandarin.14 This confirms the larger trend of more Chinese tourists going to developing countries beyond Asia and advanced economies in North America and Western Europe, making China the world’s number one tourist-sending nation in 2013 with approximately 100 million overseas trips.

In 2012, Latin America accounted for 13% of China’s total outbound investment – about $11.4 billion, a significant increase from the $120 million of 2004.

China in the Middle East: Reviving the Silk Road

Tracing what China is doing in the conventionally defined developing world has taken us to Asia, Africa and Latin America. Yet given China’s huge demand for external energy, we are not surprised at all to see China’s growing presence in the Middle East, whose energy sector ranks second behind Asia in absorbing Chinese investment (see Figure 1).

Despite China’s massive efforts to secure energy from Asia and Africa, as well as from Venezuela in Latin America, its dependency on Middle Eastern oil has risen over time. The Middle East is currently the largest exporter of crude oil to China. The share of oil imported by China from the Middle East was 48% in 1990, 49% in 2005, and 51% in 2011. It is expected that China’s crude oil imports from the Middle East will reach 70% by 2020 and continue to grow until 2035, according to the International Energy Agency. Saudi Arabia is China’s largest energy supplier with about one million barrels per day, accounting for 20% of China’s crude oil imports. Iran, another big oil supplier, contributes about 10% to China’s overall oil imports as well (see Figure 2). China has maintained a friendly relationship with both Saudi Arabia and Iran. A number of top Chinese leaders including Hu Jintao and the current president Xi Jinping have visited Saudi Arabia. And China has been dragging its feet on the UN sanctions against Iran.15 These diplomatic postures toward the Middle East conform to China’s pragmatic economic policies and interests in other energy- and commodity-rich regions such as Africa and Latin America.

But China’s interest in the Middle East does not stop with oil. “As with other regions, China has rapidly expanded its economic ties with the Middle East through trade. From 2005 to 2009, China’s total trade volume with the Middle East rose 87%, to $100 billion and reached approximately $222 billion in 2012, according to China’s official statistics. This surge pushed China to surpass the United States as the top destination for the Middle East’s exports in 2010. China’s exports to the Middle East are primarily low-cost household goods that benefit the average Middle East consumer. An example is growing numbers of Egyptians being able to afford inexpensive Chinese cars. Also, residents in the Gaza Strip suffering from the Israeli blockade depend on cheap Chinese goods in their daily lives.”16

While ambitious and already far-reaching and powerful, China’s role in reshaping the developing world will only grow and remain uncertain over time.

As many African countries have done, some Middle Eastern governments have brought Chinese contractors in to work on major infrastructure projects. Egypt has also partnered with China to develop its Suez special economic zone, a development strategy that China had used itself and promoted in Africa and the least developed parts of Southeast Asia like Laos. While China has diversified its investment in the Middle East, it is much more concentrated in the energy sector than in infrastructure (Figure 1). This further establishes China’s significant dependency on the Middle East for energy resources, namely oil. However, once we factor in the non-oil related Chinese economic activities, China’s footprint in the Middle East becomes somewhat similar to the large scope of China’s economic influence in the other three developing regions, especially in several major countries where China has moved beyond energy into infrastructure and commodities (see Figures 1 and 2). In this sense, the Middle East still marks the old destination for China’s new effort to revive the ancient Silk Road through Central Asia.

The Middle East still marks the old destination for China’s new effort to revive the ancient Silk Road through Central Asia.

China’s Ambitious and Uncertain Role

Judging by a sampling of evidence across the four developing regions, we characterize China’s role as very ambitious and yet uncertain. The ambitious aspect is increasingly fueled by China’s abundant surplus capital in both private and public hands that may have a stronger effect on the urban landscape and transport infrastructure of developing countries than on its quest for the latter’s energy and commodities.

On the bank of the Mekong River in Cambodia’s capital city Phnom Penh, the $700 million Diamond Island Riviera, a joint venture mixed-used development project involving a Chinese company, includes three 33-story condominium towers, a shopping mall, a hospital, an international school and two pedestrian shopping streets with signs in Mandarin. Before its scheduled completion in 2017, Chinese buyers, especially Shanghainese, are already buying the condos in cash as investment properties.17

It is again in Africa where the transport infrastructure is the poorest in the developing world that China is scaling up its investment most aggressively. On his recent four-country tour of Africa, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang committed to set aside $2 billion for an African Development Fund and promised his support for a high-speed rail network connecting African capitals. As a start, China Railway Construction Corporation made a $13.1 billion deal to build an 860-mile high-speed railway in Nigeria that would employ more than 4,000 workers during construction, and 5,000 more afterward.18 Claiming no-strings-attached, China’s ambitious effort can deviate from the precedent of Western colonial powers who had built highly limited transport infrastructure for shipping out their craved commodities from Africa. Yes it is uncertain that the Chinese will succeed where the earlier powers largely failed.

As further evidence on its ambition to build the developing world’s urban and transport infrastructure, China is funding and building Nicaragua’s lifelong dream in having its own canal since the 19th century, when it rivaled Panama for control of the waterway. In August 2013, President Daniel Ortega announced that a $40 billion contract had been signed with a Hong Kong-based Chinese company that would design a route and start construction in December 2014 and manage the canal for 50 years. Estimated to cost as much as $60 billion, an infrastructure project of this massive scale is very uncertain in terms of returning investment to China. Yet China might not be looking for a quick return on investment, but to control a trade route independent from U.S.-managed Panama.19

The uncertain aspect of China’s strong role has also run into trouble in the Middle East. Despite China’s political advantage in taking a somewhat neutral position regarding Iran under West-imposed sanctions in order to continue buying its oil, Iran’s Ministry of Oil has recently removed China from the project to develop the South Azadegan oilfield because of long delays. This puts China’s non-political or no-strings-attached approach to dealing with developing countries, especially those with an authoritarian domestic system and a precarious international status, to test or at risk.

While ambitious and already far-reaching and powerful, China’s role in reshaping the developing world will only grow and remain uncertain over time. It highlights the ongoing debate about whether China merely exploits commodity and energy resources in developing countries as the old West or truly promotes national and local development through its overseas infrastructure construction and other positive means as a new global power. This debate will not be settled for a long time as we continue to scrutinize China’s powerful role in shaping the developing world during the 21st century.

June 9, 2015

Helicopter or hands-off: today’s parents can’t seem to win

【可怜天下父母心】

Whether you are over-protective or more laissez-faire, the chances are that someone, somewhere will be criticising your parenting style.

Jennie Bristow

瞧,妈妈来了!

Carol Dweck, professor of psychology at Stanford University in California, has criticised “highly educated parents and academic schools” for producing, in the words of a Sunday Times headline, a “generation of no-copers” who achieve perfect grades in school but “cannot cope with the real world”.

“The idea that children have to have a string of A grades is a terrible thing”, Dweck told The Sunday Times, putting the blame for all these A grades on “parental influence”. “In the past few generations we have seen the emergence of highly educated mothers … They schedule all these activities and advocate for the child.”

Dweck is alluding to the phenomenon of “intensive mothering” – where the rearing of children has come to be seen as a highly skilled, expensive, and challenging pursuit that demands that parents (and particularly mothers) put increasing amounts of time and intellectual energies into ensuring their children’s optimal development. Indeed, the argument that the malaise of today’s youth is down to a generation of parents who are too ambitious and overprotective to allow their children grow up is becoming an increasingly common one.

There is even a label – the “helicopter parent” – which hails from the US but, like many such cultural tropes, has been gleefully adopted over here. The helicopter parent is, allegedly, a product of the Baby-Boomer generation of parents who, indulged and self-indulgent themselves, are now importing their spoiled individualism into their own little “Mini-Me"s.

It is hardly surprising that the Baby Boomers are coming under fire for their alleged parenting styles. My research into the media and policy discussion about the Boomer generation indicates that, in recent years, it has found itself blamed for a bewildering range of social problems: from the global financial crisis to the disintegration of the welfare state. Given that parents in general seem to be blamed for an awful lot these days, Baby Boomer mums and dads make convenient scapegoats for wider anxieties about child rearing.

But when it comes to the demands of today’s parenting culture, they really can’t do right for doing wrong. The complaint about “helicopter parenting” simplifies a difficult cultural problem – widespread societal anxiety about allowing children to grow up – and presents it as a question of individual parents’ attitudes and behaviours.

Concerted cultivation

It is, of course, a problem that the younger generation is infantilised by a culture of overprotection. Children are ferried from pillar to post rather than being allowed to play outside with each other. Young adults turn up to university interviews with mum and/or dad in tow. Increasingly, young people seem unwilling or unable to handle ideas or speech that they find offensive, let alone to deal with the harder knocks of life.

Parenting comes naturally to some

In education, it is a problem that the pursuit of top grades is increasingly seen as not only the main goal of education, but a task to be undertaken by parents themselves. The relentless pursuit of what the US sociologist Annette Lareau has termed “concerted cultivation” speaks to a one-sided approach to growing up, where instrumentalist, individualised concerns about academic and career success often seem to take the place of a wider focus on the good society, or the life well lived.

But can this all be the fault of pushy, highly-educated, helicopter parents? The deeper problem is the “double bind” of parenting culture in which parents are exhorted to protect their children from an expanding range of physical harms, emotional challenges, and perceived slights. When parents are continually told that their paramount concern should be the safety and success of their children, no wonder kids are scared to venture out alone and parents end up doing their homework for them.

Double bind

The helicopter parent trope presents the parent trying her hardest to meet the impossible demands of child-centred parenting – often involving a significant financial, emotional, and time cost – as a selfish “tiger mother” who is setting her child on the path to anxiety and self-harm.

Stop whining Jemima, you are going to ballet class and that’s all there is to it.

Meanwhile, parents who lack the economic, cultural or personal resources to engage in helicopter parenting are also frowned upon, for not being involved enough in their children’s education, or concerned enough about their health, safety, or emotional well-being. Just look at the official opprobrium directed at parents who allow their children to get a bit fat, miss a bit of school, fail their exams, or break a limb in an unsupervised playground.

Our culture may sneer at helicopter parents – but it is even less accepting of parents who can’t, won’t, or simply don’t want to hover over their children every minute of the day. Indeed, reading US sociologist Robert Putnam’s new book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, you would be forgiven for thinking that the only thing standing between a child’s half-decent future and the slough of poverty and despondence is their parents’ ability to invest in an Ivy League education and improving extracurricular activities around the clock, while also finding the time to sit down to a “family meal” every day of the week.

We know, deep down, that such “paranoid parenting” is unnecessary, unappealing, unattainable – and probably unkind. But so great is the fear of what might happen if they don’t do it that many parents find themselves pushed in this direction.

The existence of the double bind of parenting culture indicates that what is at stake here is not simply the alleged failure of some parents to live up to an ideal parenting standard. Rather, the idea that parents can do right by their children – whatever they do – is held in question.

Media and policy circles are filled with people issuing their own contradictory warnings and prescriptions about what children should eat, how they should play and what parents should do – while nobody seems to want to listen to the parents themselves.

《金融时报》

Ukraine set to become top corn exporter to China in first half

Beijing looks to diversify grain purchases

Call it corn diplomacy. Ukraine is set to become China’s top supplier of corn in the first half of 2015 as both countries reap the benefits of closer trade relations and Beijing looks to diversify its grain and oilseed purchases.

The latest customs data for May shows China imported 403,881 tonnes of corn — mainly used as livestock feed — of which almost 95 per cent came from Ukraine. This takes the total imports from Ukraine — the bread basket of eastern Europe — to 1.55m tonnes for the first five months of the year, or nearly 90 per cent of China’s overseas corn purchases.

Chinese corn imports

Ukraine has established itself as China’s top corn exporter at a surprising pace since its first ever corn shipment to the country in 2012 after Kiev and Beijing signed a $3bn loan-for-corn deal. Ukrainian agricultural groups have sought investment and export deals with Chinese companies such as Cofco, the state-owned grains trader.

The eastern European country’s ascent has come at the expense of the US, which until last year was the top corn exporter to China. For the first five months of this year, China imported a total of 45,000 tonnes from the US, down 95 per cent from the same time last year.

Ukraine’s deepening relationship with China will support the country’s struggling agricultural sector amid continuing tensions with neighbouring Russia. Meanwhile, imports from Ukraine help satisfy China’s growing demand for grains and meat.

But Ukraine is not the only eastern European exporter to make a mark in China this year. Corn from Bulgaria totalled 99,000 tonnes in the first five months, up by 23 times.

Some economists suggest that the rising imports from eastern Europe fit in with China’s new “Silk Road” plan, which aims to upgrade road and rail links between Europe and Asia while also revitalising maritime routes across Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean.

“Ukraine is on the new trade route to Europe that China wants to develop. It also meshes with China promoting investment and infrastructure in parts of the world that are neglected,” said Fred Gale, senior economist at the US Department of Agriculture.

Compared to soyabeans, where China consumed almost two-thirds of the world’s exports last year, the country is not a large importer of corn. In 2014 it bought 2.6m tonnes from overseas producers, less than 2 per cent of total world trade.

Since 2013, bumper domestic crops have meant that state warehouses are bulging with inventory. Moreover, both international and Chinese agricultural authorities have underestimated the level of corn inventories, leading to a reduction in import forecasts.

Nevertheless, as meat consumption continues to rise and agricultural output growth hits a wall due to the lack of water, land and labour, China is expected to turn to imports.

Reducing its reliance on food commodities from one country, namely the US, is another likely reason behind the Ukraine strategy. This will be deeply worrying for US corn exporters.

In soyabeans, for example, Brazil overtook the US as the top exporter to China in 2013, and last year accounted for 46.5 per cent of the country’s overseas purchases by value compared to the US, which accounted for 40 per cent, according data from the International Trade Centre in Switzerland.

《World Affiars - LatinAmerican Post》

What Does the TPP Mean for LatAm?

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a proposed trade deal among twelve Pacific Rim countries, including the United States, is largely discussed in the context of President Barack Obama’s administration’s “pivot to Asia.” However, three Latin American countries, Mexico, Peru, and Chile are also involved in negotiations. The TPP will not transform these economies, says CFR's Shannon K. O’Neil, but it will "allow them them to enter the world stage with similar rules that are applied to the United States and other [wealthy countries]." She says that for these countries to reap the benefits of the TPP they will have to produce more value-added goods in a competitive way.

How significant is the TPP for the Latin American countries involved?

It’s an important trade agreement. Mexico, Peru, and Chile will be part of this larger group, which makes up almost 40 percent of world GDP. These countries have decided that their path forward is to embrace globalization and free trade agreements. They’ve signed trade agreements with many different nations, and this would be a quite-large regional bloc.

However, these countries already have free trade agreements, and [in the case of Peru and Chile, produce] commodities, whose tariffs aren’t high to begin with. I don’t see the TPP as transformative for these countries, but it does allow them to enter the world stage with similar rules that are applied to the United States and other [wealthy countries], and will potentially give exporters access to more markets.

The TPP can provide opportunities if the Latin American nations that are involved can climb the value-added chain, invent, say, the next Apple computer, and produce these products in competitive ways. The challenge is that other participants, for instance Vietnam [another member of the TPP] are also trying to upgrade their exports. Being part of the TPP is like joining a club. You have to perform when you get there.

Colombia is the only member of the Pacific Alliance, a trade bloc that spans Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, that is not part of TPP negotiations. Why hasn’t Colombia been included?

While APEC [Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation] membership is not required, all countries involved in TPP are members; Colombia, though it has applied for APEC membership, has not yet been admitted. The countries that began the process of forming the TPP are wary of expanding to new nations in this initial negotiation. Colombia has expressed its interest in joining, but the thought is that they wouldn’t be included in this round because adding another country to the bloc means adding yet another set of demands to already difficult negotiations.

Through NAFTA and bilateral trade agreements, the United States already does nearly $500 billion in annual trade with Mexico, and $15.8 billion and $28.3 billion with Peru and Chile, respectively. Will this boost trade between these countries?

It won’t boost trade directly between the United States and these countries because we already have free trade agreements. The TPP is coming on the back of the Pacific Alliance, which has already spurred some integration. Still, it could—particularly in the case of Mexico—deepen existing regional supply chains that create products such as autos, electronics, aerospace[craft], by opening up new markets, reducing tariffs, and getting into the Japanese and these other Pacific markets. It provides a larger market for companies that have already taken advantage of NAFTA.

How strong is domestic support for the TPP in Mexico, Peru, and Chile?

Support for the TPP and trade in general in these countries is higher than it is in the United States. There is a sense in these countries that openness is the way to go. Of course, there are some people who disagree, but the political debates aren’t as divided as they are in the United States. Public opinion polls show that many of the citizens of these countries believe in free trade.

What are some of the sticking points for Latin American countries in trade talks?

Intellectual property rights is an issue—the challenge of whether prices on particular drugs will go up and make them unaffordable to segments of the population. The concern is that protection of intellectual property rights could make it difficult for countries to produce, say, generic AIDS drugs or other types of [life-saving] drugs.

In Mexico, there are worries about changing current rules of origin— or where parts are made—percentages for autos, and opening up the North American industry to heavy Japanese competition. So one important issue is domestic-content levels and for Japenese cars vis-a-vis North American–created cars. Here, Mexico and the United States want a higher percentage of the production to be in North America; Japan wants the opposite. Every country comes with a list of things that are important to them, and Latin American countries are no exception. Overall, I think they’re a lot closer to the United States than some other nations in terms of what they want.

Could the TPP negatively affect neighboring countries—such as Brazil, Argentina, or Venezuela—that are not party to the agreement?

The TPP will likely further separate the economic paths these countries have chosen. Embracing the TPP means that you’re betting your economic growth will come from exports, imports, and exposure to the rest of the world in ways that some of these other countries—which have chosen more protected, state-led industrial policies—have not at least yet decided to do. The question is, once the TPP is in effect, would those countries down the road want to join? They could later if their populations and governments felt it would be beneficial.

Mexico’s economy has a strong manufacturing base, while Peru and Chile’s economies are more reliant on commodity exports. How does that affect what each country stands to gain or lose in a potential agreement?

There’s a real question of how important the TPP will be in the short-to-medium term. Mexico can probably take advantage the quickest because of its diversified manufacturing base. Within the Pacific Alliance agreement, Mexico will probably benefit the most because it has a different economic base than the other countries. Mexico complements rather than competes with what Chile, Colombia, and Peru produce.

TPP can deepen and strengthen Mexico’s integration with the United States and protect already linked sectors and industries from losing ground. If Mexico was not part of the TPP, it might be hard to continue manufacturing cars and airplanes across borders, as different rules could break up current U.S.-Mexico supply chains. Unlike the South American nations, Mexico has the geographic benefit of being close to the United States and Canada.

Is labor cheap enough in these countries—particulalry in Chile, which the World Bank designates as high income—to make these countries competitive vis-a-vis the deal’s Asian parties?

It’s increasingly a question of productivity of labor. Particularly in advanced manufacturing, where more and more is done by robotics wherever you do it—whether in China or South Carolina, you have the same plant and the same robotics. What you need is a skilled workforce that can use that equipment. Then, a country such as Chile, if it has the needed skilled workforce, might be as attractive. But Chile would have transportation and logistics costs that Mexico doesn’t.

China has dramatically increased trade and investment in Latin America. Would the TPP, which some say is a counterweight to Chinese influence, affect that?

The TPP doesn’t necessarily affect these coutries’ relationships with China. It could complement China. President Obama has said China could join someday. Being part of the TPP would not preclude Latin Amercian nations from trading with China. Most of what China buys from Latin American countries are commodities. They don’t buy cars or many value-added goods. They prefer to send value-added goods. [The TPP] shouldn’t change the flow of copper, iron ore, soy, and the other myriad commodities. It could potentially open other markets for those products in a way that will allow them to diversify their economic base.

Council on Foreign Relations

Interviewee: Shannon K. O'Neil, Senior Fellow for Latin America Studies and Director of the Civil Society, Markets, and Democracy Program

Interviewer: Danielle Renwick

《Brookings》

TPP? TTIP? Key trade deal terms explained

《Peterson Institute》

What Economic Models Tell Us about the TPP

Understanding the Estimated Gains from Trade Pacts

| Table 1 Estimated income and export gains from implementation of TPP, 2025 |

|||||||||

| TPP-12 | Baseline GDP 2025 (billions 2007 dollars) | Income gains |

Baseline exports 2025 (billions 2007 dollars) | Export increases |

|||||

| Billions 2007 dollars | % change from baseline | Billions 2007 dollars | % change from baseline | ||||||

| Australia | 1,433 | 7 | 0.5 | 332 | 11.1 | 3.4 | |||

| Brunei | 20 | 0 | 0.9 | 9 | 0.2 | 2.6 | |||

| Canada | 1,978 | 9 | 0.4 | 597 | 13.8 | 2.3 | |||

| Chile | 292 | 3 | 0.9 | 151 | 3.7 | 2.4 | |||

| Japan | 5,338 | 105 | 2.0 | 1,252 | 139.7 | 11.2 | |||

| Malaysia | 431 | 24 | 5.6 | 336 | 40.0 | 11.9 | |||

| Mexico | 2,004 | 10 | 0.5 | 507 | 19.1 | 3.8 | |||

| New Zealand | 201 | 4 | 2.0 | 60 | 4.1 | 6.8 | |||

| Peru | 320 | 4 | 1.2 | 95 | 6.0 | 6.3 | |||

| Singapore | 415 | 8 | 1.9 | 263 | 11.3 | 4.3 | |||

| Vietnam | 340 | 36 | 10.5 | 239 | 67.9 | 28.5 | |||

| United States | 20,273 | 77 | 0.4 | 2,813 | 123.5 | 4.4 | |||

Simon Johnson

What Is the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) Really All About?

TPP is a very important potential trade agreement, primarily because it will establish the rules that can be included in this kind of deal going forward, including with other countries such as China. But in this kind of arrangement, it is essential to examine and understand the details in order to comprehend the full nature of the commitments (as well as the gains or losses).

环球做了个分析,有意思。

对高铁和汽车业,分析的对。说汽车业失败,是因为绝大部分核心技术掌握在外国企业手里,中国汽车厂家除了低价,没什么招数。低价,最后地方政府得补贴,实际上政府百姓亏钱,亏大了。

只是这分析片面、肤浅,不是治国良策。当然环球如此说,不是怪事。

高铁崛起和汽车业失败,为什么?

《环球网》2015.06.21

中国高铁崛起背后:始终保持对国内市场统一领导

6月18日,中铁二院与俄罗斯企业组成的联合体,就中标的莫斯科-喀山高铁项目的勘察设计部分与俄罗斯铁路公司正式签约,项目合同金额约24亿人民币,这是中国高铁走出国门“第一单”。该段铁路设计时速最高将达到400公里,是名副其实的地面铁路“第一速度”。

实际上,俄方一开始的合作伙伴并非中国,而是德国。两国合作成立联合体,工作三年之后,依然解决不了该项目的多种技术难题。在此情况下,俄方转而选择了 中国。根据合同,中方不但要承担该项目的勘察设计,而且要负责投融资、施工建设和运营管理。这意味着,中国高铁走出国门“第一单”是一个检验和体现中国高 铁综合实力的整体项目。

德国电视一台网站的一篇文章说,现在大家一说到手表,就会想到瑞士制造;一说到机器,就会想到德国制造;一说到电子产品,就会想起日本制造; 一说到名牌奢侈品,就会想到法国、意大利制造;如今若说起高速列车,人们自然会想到中国制造。

的确,中国高铁在技术体系、制造与施工能力、成本与金融支持等方面,已在国际竞争中处于整体优势地位。

2007年以前,中国还没有一条真正意义上的高速铁路,而今天中国高铁运营里程已达一万六千多公里,占世界高铁总里程的一半以上,且在多国承揽高铁工程。在短短的几年里,中国高铁能取得如此显赫甚而令人惊异的成绩,是后来居上、弯道超车、跨越发展的结果。

那么,为什么我国很多行业无法实现后来居上、弯道超车,而偏偏高铁能够做到呢?这里面的因素很多,但笔者以为,很重要的一条经验就是我国铁路部门始终保 持着对国内市场的统一领导。这种统一性形成了对外的唯一性,能够有效避免内部的各自为政、相互损害,从而集中力量以庞大的国内市场为筹码,迫使西方跨国公 司不得不以转让核心技术作为进入中国市场的前提条件。

在中国高铁崛起之前,世界上掌握高铁技术的跨国公司有德国西门子集团、法国阿尔 斯通集团、加拿大庞巴迪集团和日本的日立与川崎重工。实际上,这些掌握高铁先进技术的跨国公司极不情愿向中国转让技术;但是令其垂涎的中国市场因铁道部的 把守而不得随意进入,故不得不以技术作为门票。就这样,铁道部先后把加拿大的轨道技术、法国的电控系统、日本的牵引系统和德国的行车控制系统陆续引进了中 国,并在此基础上消化、吸收、集成、再创新,逐步构成了比其中任何一个国家都完整的升级版的先进技术体系。一位铁路系统的领导同志谈及这个问题,坦诚而自 信地说:“我们承认中国高铁的技术来自德法日等国,是引进学习的结果;但我们也可以自豪地对他们讲,我们吸收、集成、再创新,现在中国高铁的技术比他们全 面,比他们先进,比他们更有竞争力,是一个整体的优势。”

相比之下,我国汽车业完全是另一种情况。本来,中国汽车业拥有和中国铁路一 样的优越条件:市场庞大,拥护众多,发展潜力巨大,如果体质机制对头,完全可以将世界汽车强国的最先进技术全部引进中国,然后加以集成创新,进而使中国成 为世界汽车最强国。然而,由于缺乏全国性的行业统筹,各地汽车企业在地方政府支持下,各自为政,相互杀价,把外企进入中国市场的门槛降得很低,导致德、 日、美、法、韩汽车厂商在不转让技术的情况下,轻易实现了对中国市场的占领与垄断。最后的结果是,市场让光了,道路堵塞了,空气污染了,利润流失了,而技 术没换来。这种情况,不但给中国造成巨大损失,甚至影响了中国的产业升级。

类似的情况还有钢铁业和稀土业。按说,中国是铁矿石的最大 买家,在国际市场上应该有定价权,但实际上没有。因为,各个钢铁企业各自为政,相互抬价,把铁矿石价格越抬越高,结果全中国的钢铁业把利润拱手送给了澳 洲、巴西的铁矿老板。稀土,中国是世界上最大的卖家,按理更应该有定价权,但实际上也没有。因为,各个稀土企业各自为政,相互杀价,把珍贵的稀土杀成了白 菜价,把利润拱手送给了美日欧。这两个行业的惨状,究其根源,就是在行业体制上,缺乏统一领导和行业统筹,这和铁路部门的情况形成鲜明反差。

经验教训证明,大企业如果主要面对国内竞争,应加以分拆,以利于充分竞争,让广大消费者受益;反之,如果主要面向国际竞争,则应实行企业整合和行业统 筹,以形成统一的、强大的国际竞争力。分拆,还是整合,应视具体情况而定。总之,几十年来新自由主义把中国害惨了,不能再听他们忽悠了。

《纽约客》

Journey to Jihad

Why are teen-agers joining ISIS?

By Ben Taub

Jejoen Bontinck at his home in Antwerp, in December, 2014. The Belgian authorities who interrogated him emerged with a portrait of the radical Islamist recruitment process

In 2009, a fourteen-year-old Belgian named Jejoen Bontinck slipped a sparkly white glove onto his left hand, squeezed into a sequinned black cardigan, and appeared on the reality-television contest “Move Like Michael Jackson.” He had travelled to Ghent from his home, in Antwerp, with his father, Dimitri, who wore a pin-striped suit jacket and oversized sunglasses, and who told the audience that he was Jejoen’s manager, mental coach, and personal assistant. Standing before the judges, Jejoen (pronounced “yeh-yoon”) professed his faith in the American Dream. “Dance yourself dizzy,” a judge said, and Jejoen moonwalked through the preliminary round. “That is performance!” Dimitri told the show’s host, a former Miss Belgium named Véronique de Kock. “You’re gonna hear from him, sweetie.”

Jejoen was soon eliminated, but four years later, when he least wanted the attention, he became the focus of hundreds of articles in the Belgian press. He had participated in a jihadi radicalization program, operated out of a rented room in Antwerp, that inspired dozens of Belgian youths to migrate to Syria and take up arms against the government of Bashar al-Assad. Most of the group’s members ultimately became part of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, joining more than twenty thousand foreign fighters engaged in the conflict in Syria and Iraq. Today, ISIS controls large parts of both countries. With revenue of more than a million dollars a day, mostly from extortion and taxation, the group continues to expand its reach; in mid-May, its forces captured the Iraqi city of Ramadi, the capital of Anbar province, and, last week, they took control of Palmyra, in Syria.

About four thousand European jihadis have gone to Syria since the outbreak of war, in 2011, more than four hundred from Belgium. (It is estimated that at least a hundred Americans have joined the fight.) The migration of youths from seemingly stable and prosperous communities to fight with radical Islamists has bewildered not only their families but governments and security forces throughout Europe.

Tens of thousands of Muslim civilians and moderate rebels, mostly Sunnis, died in the early stages of the war in Syria, and many people have argued that the European jihadis were motivated by humanitarian concerns. But thousands of pages of Belgian federal-police documents—including wiretaps and interrogations of jihadis who fought abroad and later returned—show that, even before ISIS announced its presence in Syria, the primary objective for many Europeans, including those in Jejoen’s group, was to establish an Islamic caliphate through violence. “We were already talking about terrorism in 2012,” a Belgian security official told me. “But, at that time, no one wanted to talk about terrorism,” because Assad insisted that the opposition was composed of extremists. The Belgian security official said, “It was very difficult to say, ‘Well, yes, he is right, because our Belgians are terrorists.’ ”

After eight months in Syria, Jejoen returned to Belgium, where he was promptly arrested. Jejoen’s lawyer says that the authorities interrogated him for more than two hundred hours. They emerged with a portrait of the radical Islamist recruitment process, as well as an account of the workings of ISIS. “We are sure that he probably didn’t tell us everything,” the Belgian security official said. But he added, of what Jejoen did divulge, “We haven’t found one element that is not correct.”

I met Jejoen several times last winter, usually at his mother’s home, in Antwerp, where he was awaiting sentencing in Belgium’s largest terrorism trial. He mostly avoided discussing his experience in Syria, preferring to play Counter-Strike on a laptop. But transcripts of the police interrogations show that he was, as his father calls him, “the golden witness.”

In 1994, Dimitri Bontinck, then a twenty-year-old night-club bouncer, travelled to West Africa on holiday, where he met and married Rose, a Nigerian woman with strict Catholic beliefs. Their son, Jejoen, was born in southern Nigeria the following year; the family moved to Belgium shortly afterward. Dimitri told me that he served in the military, and then in a U.N. peacekeeping mission to Bosnia, before taking an administrative position in the Antwerp court system. When Jejoen was eight, the Bontincks had a daughter, Iris. Family life was “always in harmony,” Dimitri said this winter, in his one-room apartment in Antwerp. Now forty-one, Dimitri has a buzz cut and an athletic build that belies his reliance on whiskey and Marlboros.

Jejoen was brought up Catholic, and enrolled in a prestigious Jesuit academy called Our Lady College. “I think that was the best period of his life,” Dimitri said, praising the school’s structure. But when Jejoen was fifteen he started doing poorly in math, and had to transfer to a remedial high school. Then his girlfriend dumped him. At that point, Dimitri told me, Jejoen “fell down in a black hole.”

Jejoen described this period to the police as one of “searching” and “looking for an alternative to the pain.” When he was sixteen, he started dating a Moroccan girl at his new school, who introduced him to Islam, and told him that if he wanted to keep seeing her he had to learn about the religion. Jejoen searched “What is Islam?” online, and, on August 1, 2011, the first day of Ramadan, he converted at De Koepel Mosque.

De Koepel, which means “The Dome,” was founded in Antwerp, in 2005, by Belgian converts. At the time, no mosque in Belgium conducted Friday prayers in Dutch, so Muslims who didn’t speak Arabic or Turkish had difficulty following sermons. De Koepel became a home not only for converts but for hundreds of second- and third-generation Moroccans and Turks.

On Fridays, the ground floor of the mosque is lined with four rows of men and boys at prayer. Women pray upstairs, and watch the imam deliver his sermon by live video. At De Koepel, Jejoen prayed five times a day and closely followed the sermons of Sulayman Van Ael, the imam at the time, who took a relatively moderate tone, emphasizing charity work and the five pillars of Islam.

Dimitri found the conversion frustrating. “A family is supposed to eat together at the table,” he told me, but, when Jejoen adopted halal dietary restrictions, family dinners grew less frequent. Still, Dimitri saw Jejoen’s new habits as a kind of teen-age rebellion. “What can you do?” he said.

In November, 2011, three months after Jejoen’s conversion, a neighbor named Azeddine invited him to visit the headquarters of Sharia4Belgium, at 117 Dambruggestraat. The mission of Sharia4Belgium, established the previous year, was to transform Belgium into a state governed as the cities of Raqqa, in Syria, and Mosul, in Iraq, are today: replace the parliament with a shura council and the Prime Minister with a caliph; stone adulterers and execute homosexuals; and convert or banish all non-Muslims, or force them to pay jizya, a tax levied on those who don’t adhere to the faith.

The leader of Sharia4Belgium was Fouad Belkacem, a thirty-three-year-old militant preacher. A slight, bespectacled, balding man with a full dark beard, who usually wears a long djellabah, Belkacem was born in Belgium to Moroccan parents. In his twenties, he wore jeans and was clean-shaven. He was arrested for burglary and forgery, for which he spent time in jail. After he got out, he worked as a used-car salesman and volunteered at a youth center, where, according to a social worker named Peter Calluy, he propagated homophobia and anti-democratic ideas.

Anjem Choudary, a British radical Islamist, told me that in March, 2010, Belkacem visited him in London to ask his advice about how “to start something in Belgium.” Choudary, who is forty-eight, and has a long, graying beard, has acted as a spokesman for various radical groups, such as al-Muhajiroun and Islam4UK, that have since been banned under U.K. terrorism laws. He has been arrested on several occasions for organizing illegal protests, and several of his associates have committed acts of terrorism, including, in 2013, the killing of Lee Rigby, a British soldier, on the streets of London. But Choudary, who is closely monitored by security services, has never been convicted of any terrorism-related charges.

“I went through the history of al-Muhajiroun, how we set it up,” Choudary told me one afternoon last winter, in a London café. “You can’t do what the prophets of old did, which was to stand on the hills and the mountains and address people,” he said. “The hills and mountains today are Sky News, CNN, Fox News, the BBC.” We were meeting just a few hours after the murders of twelve people at the office of Charlie Hebdo, and Choudary proudly showed me his statement on Twitter: “Freedom of expression does not extend to insulting the Prophets of Allah, whatever your views on the events in Paris today! #ParisShooting.” He was delighted by the reaction. “That’s not bad, actually—two hundred and eighty-six retweets?” he said. A few minutes later, Choudary’s phone rang. “Fox News, tonight,” he said, smiling. Sean Hannity wanted Choudary to represent the Muslim view.

Choudary described Belkacem as an “incredibly receptive younger brother.” Belkacem returned to Belgium and started Sharia4Belgium that March. By the time Jejoen arrived, in November, 2011, the group had publicly burned an American flag to commemorate the attacks on the World Trade Center and, in a Facebook post, applauded the news that a young politician, who belonged to an extreme-right political party that denounced Muslims and immigrants, was dying of cancer. Later, on YouTube, Belkacem declared Sharia4Belgium’s intention to destroy city monuments, and members travelled to the Netherlands to disrupt a lecture delivered by two openly gay Muslims. Every weekend, the group held demonstrations in public squares in Antwerp and Brussels, as well as in the small towns along the train line between them. Sharia4Belgium enjoyed the protection of the same free-expression laws that the group sought to dismantle. “It was a little bit irritating,” the Belgian security official told me, but “it’s very clear that you’re not going to demolish democracy in Belgium by giving flyers to people.”

Belkacem also established contact with jihadis in other countries. “He had connections with people in Denmark and other parts of Europe,” Choudary told me. One prominent jihadi ideologue in the Middle East, Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, advised Belkacem to focus on recruitment. The goal was to establish Sharia law not just in Belgium but everywhere.

When Jejoen first visited the headquarters of Sharia4Belgium, Belkacem asked him if he was prepared to learn the Koran “without any distortion or editing or interpretation.” He then sent Jejoen back to De Koepel with a set of questions for Van Ael, the imam, including one about the validity of hatred in the name of Allah. “Van Ael literally told me that this was the ideology of Sharia4Belgium,” Jejoen said, “and that I should turn away from it.” But Belkacem had quoted verses from the Koran and the hadith to convince Jejoen of his interpretation of Islam. Van Ael’s response only affirmed Jejoen’s belief in Belkacem’s message.

“Typical recruitment patterns in Europe and the West tell us that it helps if that person doesn’t have a religious background,” Maajid Nawaz, a former Islamist recruiter who now runs a counter-extremism think tank in London called Quilliam, told me. Converts and the newly devout, “dislocated from the traditional hierarchies” of Islam, are less likely to challenge a purported authority on religious matters.

Jejoen adopted a Muslim name, Sayfullah Ahlu Sunna. He also took a kunya, a kind of nickname that in the Arab world reflects familial relations and endearment but in jihadi circles is also used to obscure identity. Jejoen’s kunya was Abu Assya; Belkacem’s was Abu Imran. In Sharia4Belgium, most members, who were known as brothers, addressed one another by their kunyas.

Belkacem ran an intensive twenty-four-week program of ideological training. He began by declaring that the world was divided into two groups: Muslims and non-Muslims. In mainstream mosques, nuance and interpretive religious scholarship are encouraged. Notes collected in police raids show that Belkacem’s lessons reduced the world to flowcharts and categories: Muslims versus infidels; Sharia versus democracy. Belkacem taught the brothers that most imams ignore discussions of jihad and martyrdom because they want to keep state funding. Bart Buytaert, the chairman of De Koepel, told me, “Belkacem and Sharia4Belgium accused us of being non-Muslims.”

Jejoen began spending most of his free time at the headquarters of Sharia4Belgium. One of the brothers regularly led martial-arts classes there, which some members supplemented with kickboxing training at a nearby gym. Choudary, who is identified in police files as a financial supporter of Sharia4Belgium, lectured remotely, through a video-chat Web site called Paltalk. Choudary’s mentor, Omar Bakri Muhammad, a radical preacher who became known in London as the Tottenham Ayatollah, did the same from Lebanon, where he lived after being exiled from the U.K. Choudary also fostered an exchange program, through which Belkacem’s followers came to England to study with him, and some of his followers visited the Sharia4Belgium headquarters. On one occasion, Choudary and a group of his followers travelled to the Netherlands, to deliver a lecture for the brothers of Sharia4Belgium and its partner organization Sharia4Holland “about the methodology to overthrow the regimes.” The visit was captured by a documentary crew from the Belgian channel RTBF. “I come from England in order to radicalize the youth in this country,” Choudary said. One Sharia4Belgium member remarked to a British counterpart, “Sometimes you need laptop, sometimes you need Kalashnikov.”

Members were discouraged from sharing information about the group with their parents. Choudary told me, “There’s no need for them to be informed.” When Jejoen’s parents asked where he was spending so much time, he said that he was playing video games with friends. Jejoen routinely came home late and struggled to get up in the mornings. “Step by step, he started to neglect his responsibilities,” Dimitri said. Some of the brothers dropped out of school. Many lost interest in friends who weren’t affiliated with Sharia4Belgium. Choudary said that it was “natural” that members would “distance ourselves from our previous life, and our previous friends and behavior.”

Dimitri found out about his son’s membership in Sharia4Belgium in late 2011, shortly after Jejoen joined the group. Then a brother named Michael Delefortrie—who had named his two sons for founding members of Al Qaeda—was arrested for trying to sell a Kalashnikov online. Belkacem held a press conference that was covered by an evening-news show. Dimitri was watching television at home that evening when he spotted Jejoen next to Belkacem on the screen. Dimitri told the police that Jejoen was a minor, and asked them to extract him from the group, but he says that a judge told him that there was nothing they could do.

Then, one evening in February, 2012, the principal of Jejoen’s high school warned the police that Jejoen had threatened to “purge” the school. A juvenile court ordered Jejoen to see a counsellor, but, according to Dimitri, she didn’t know anything about Islam. “How you can solve a problem if the other parts don’t even know where is Mecca?” he said. Dimitri started visiting the Sharia4Belgium headquarters, hoping to find evidence of illegal activity. “I always had a feeling that something is going wrong inside that clubhouse,” he told me. Dimitri and Rose invited Belkacem to their house, but he was adept at deflecting their inquiries, and Dimitri never saw any extremist materials inside the headquarters. Though police raids later discovered fundamentalist literature—including a pamphlet with instructions on how to beat women “with a corrective and educational intent”—it was kept in members’ homes, not at the Sharia4Belgium headquarters.

As part of the indoctrination program, the brothers often watched archived lectures by Anwar al-Awlaki, the American-born imam who was killed in a U.S. drone strike in Yemen a little more than a month before Jejoen’s first visit to Sharia4Belgium. They also watched footage of battles in Afghanistan, Chechnya, and other jihadi conflict zones, and came to think of the mujahideen in the videos as selfless heroes defending Islam against corrupt crusaders. One day, they watched a video of a beheading. Members discussed where they’d like to fight in the future, from Libya to Somalia to the Seychelles. “You sit for months in a group in which jihad is considered quite normal,” Jejoen said.

Jejoen continued to text girls, which was forbidden by Belkacem; one day, he ordered a brother to destroy Jejoen’s SIM card. Months later, Jejoen got in worse trouble for proselytizing on his own. Other Sharia4Belgium members said that Jejoen was using the activity as an excuse to meet girls. Belkacem accused him of practicing “exorcism.” He was temporarily suspended from the group.

Belkacem dedicated the last four weeks of the course to teaching the importance of loyalty toward Muslims, and disavowal of non-Muslims. The prospect of excommunication kept most members obedient; one brother, who was in his late teens, was required to undergo circumcision. The program’s final task was a written exam. The questions were rudimentary, including “What does Islam mean?” and “Should I vote?” (Members were discouraged from voting, on the ground that it acknowledged the legitimacy of the democratic process.) One student, whose exam was found in the police raid, scored eighty-four per cent. Today, he is believed to be a member of the religious police in Raqqa.

By February, 2012, Belgian police were wiretapping phone calls within the group. But many of the trainees were petty criminals familiar with police tactics, and a former Belgian counterterrorism investigator told me, “They know the way. They buy a cheap cell phone, and they throw it away.”

Belkacem never explicitly instructed his followers to fight in Syria. But he taught them that martyrdom on the battlefield, which he called “pure Islam,” yielded the greatest reward in paradise. “The battle is not only an invitation, but an individual obligation,” Walid Lakdim, a Sharia4Belgium member, said in a police interrogation after returning from Syria.

At the time, the Syrian revolution was not known for its foreign jihadi element. The face of the rebel side was the Free Syrian Army, a loose affiliation of groups, some of which were led by officers who had defected from Assad’s government forces after refusing to shoot unarmed protesters. The rebels spoke of the eventual triumph of democracy over Assad’s brutal regime.

In 2011, a Sharia4Belgium member named Nabil Kasmi travelled to Lebanon, where he visited Choudary’s mentor, Omar Bakri Muhammad, who was living under house arrest in Tripoli, a coastal city in the north. Kasmi returned to Belgium a few months later, but, in March, 2012, he came back to Lebanon. At the same time, other Sharia4Belgium members travelled to Yemen, where they were detained and subsequently deported, under suspicion of trying to join Al Qaeda. Then, in May, Kasmi crossed into Syria. Jejoen told police that Kasmi called Sharia4Belgium headquarters, declaring that “he was in Syria to fight.” According to a Lebanese military court, Bakri Muhammad and Kasmi helped a few European jihadis establish themselves in Al Qaeda-affiliated groups across the Syrian border. “Once they were ready to go to Syria,” the Belgian security official said, “they had a whole operational network,” owing to Sharia4Belgium’s ties to Bakri Muhammad and Choudary. (Choudary denied sending people to Syria, and said, “If I were to send someone somewhere, I would go there first.”)

The following month, Belkacem was arrested and imprisoned for instigating hate. One of his wives, Stephanie Djato, had refused to comply with a Belgian law that bans full-face coverings in public. (Though polygamy is illegal in Belgium, Belkacem has married at least two women in religious ceremonies.) When a female police officer tried to remove her niqab, Djato head-butted her, breaking the officer’s nose. Belkacem and Choudary both posted statements online, threatening retribution against the police for removing Djato’s niqab. Riots ensued in Brussels, and two police officers were stabbed by a man carrying Sharia4-Belgium literature.

With Belkacem in jail, Sharia4Belgium was rudderless. The members continued their video sessions with Choudary, who invited them to protest the Olympics, which were held in London that July. Kasmi returned to Belgium for a short period. Then, on August 20, 2012, he left for Syria again; the next day, five other members followed. In September, Jejoen and several other Sharia4Belgium members participated in demonstrations against “Innocence of Muslims,” a film that depicted the prophet Muhammad as a homosexual and a child-molester and which sparked deadly protests across the Middle East and North Africa. By October, the group had dissolved, and in the next eighteen months about fifty Belgians directly affiliated with Sharia4Belgium made their way to Syria. Those who arrived first joined groups that were later absorbed into Al Qaeda and ISIS; the others mostly joined ISIS directly. Only Belkacem stayed behind. In a long open letter, written from jail, Belkacem insisted that he was only a provocateur, comparing himself to Pussy Riot and Femen.

In February, 2013, shortly after Jejoen’s eighteenth birthday, he woke up from a dream in which Azeddine, the friend who had introduced him to Sharia4Belgium, was praying for help. They hadn’t seen each other in five months. A few days later, Jejoen’s phone rang, and a number appeared beginning with 963, the Syrian country code. It was Azeddine. Jejoen asked him who else was in Syria. “Everyone,” he replied.

On the pretext of going to Amsterdam with friends, Jejoen borrowed his father’s suitcase and packed it with a sleeping bag, warm clothes, a flashlight, and—on Azeddine’s request—night-vision goggles. Another Sharia4Belgium member, already in Syria, told Jejoen how to get to the border between Turkey and Syria. Jejoen left home on February 21, 2013, without knowing the name of the group that he would join. He expected that he “would fall martyr within a short time and would go to paradise,” he said. He believed, as he had been told, that “good deeds erase bad deeds, and jihad is the best deed” of all.

At Schiphol Airport, in Amsterdam, Jejoen dawdled so long at a Burger King that he missed his flight to Istanbul. He had forgotten his passport, too, but his Belgian identity card sufficed. He had been instructed to meet two other aspiring jihadis in Istanbul, but he ended up at the wrong airport. So he continued alone, flying to Adana, in southern Turkey, where they all finally met in a café. Together, they took a bus to Antakya, a city near the Syrian border.

A smuggler met them there and drove them to a village in the mountains, where they waited with other jihadis for the signal to cross. Once in Syria, Jejoen and his companions texted other Sharia4Belgium members and asked to be picked up. By nightfall on February 22nd, Jejoen was in a car, reunited with his friends from Belgium. “I found it strange to see them with weapons,” he told police. “I hesitated and then asked if this was what I had come for.” Soon, the car pulled up to a walled villa in Kafr Hamra, a small town on the outskirts of Aleppo. Around seventy pairs of shoes, belonging to Belgian, Dutch, and French jihadis, were arrayed on racks outside the front door. Inside, Jejoen met Amr al-Absi, the Syrian emir in charge of the Mujahideen Shura Council, a group of international jihadis whose goal was to transform the northern part of the country into an Islamic state. Absi had been severely injured in battle, and had several broken ribs and a large open wound on his left leg.

Dimitri Bontinck found a YouTube video showing several Belgian jihadis in a field with yellow flowers. One of them looked like Jejoen

Absi’s family is from Aleppo, but he was born in Saudi Arabia, probably in 1979. His older brother, a dentist named Firas, trained with Al Qaeda in Afghanistan. Amr and Firas are thought to have joined Al Qaeda in Iraq, which became the Islamic State of Iraq; the group’s aim was to establish an Islamic caliphate that would spread throughout the Middle East and beyond. In 2007, Amr al-Absi was arrested in Syria, and held in the Al Qaeda wing of Sednaya prison, with hundreds of other extremists. Four years later, in June, 2011, Assad released them. It was a turning point in the Syrian war. Assad had stated that the opposition was full of terrorists, a claim that the mysterious amnesty then fulfilled. It seemed like a calculated move to poison the nascent Syrian revolution.

Absi took up the leadership of a jihadi brigade near the Syrian city of Homs. His brother Firas had recently founded a group called the Shura Council of the Islamic State, which gained notoriety after raising the Al Qaeda flag at the border gates near Bab al-Hawa, a major crossing point between Turkey and Syria, in July, 2012. It was the first mention of an Islamic state in the Syrian civil war. The following week, the group kidnapped two European journalists, Jeroen Oerlemans and John Cantlie. Moderate Syrian rebels rescued and released the journalists a week later. Firas’s extremism was a liability to the revolution, and in September, 2012, he was kidnapped and murdered by moderate rebels. Amr al-Absi inherited his brother’s role as emir, and the group changed its name to the Mujahideen Shura Council.

In Kafr Hamra, Absi divided his fighters according to origin. Most of the Europeans, including the Sharia4Belgium members, lived in a walled villa, with an indoor swimming pool and a fountain. The Arabs, and some luckier Europeans, lived in a nearby complex, known as “the palace,” which was said to have been captured from an official in the Assad regime. It had a fuelling station, an orchard the size of a football field, and a rooftop pool.

Absi designated Houssien Elouassaki, a twenty-one-year-old Sharia4Belgium member, as the leader of the European group. When Absi wasn’t present, Elouassaki decided matters ranging from who washed the dishes to which Europeans would be allowed to join them in Syria. “It is something incredible,” his brother Abdel, who remained in Belgium, told a friend over the phone. “He is the youngest emir in the world.”

Absi’s fighters didn’t know his real name. They called him Sheikh, or Emir, or by his kunya, Abu Asir. Jejoen told police that the Belgians mostly knew him as “the big financier of everything.” Absi bought the weapons, the fuel, and the food, and when fighters were injured in battle he covered their medical expenses.

In early December, 2012, the Mujahideen Shura Council assisted Jabhat al-Nusra, the jihadi group that five months later became Al Qaeda’s official Syrian affiliate, in an attack on an Army outpost called Base 111, near the village of Sheikh Suleiman. It was Assad’s last major base west of Aleppo, and soon the Al Qaeda flag flew overhead. Absi’s group took prisoners, and initially, a jihadi said in a wiretapped call, they planned to use them for ransom or prisoner exchanges. Instead, “Everyone cut someone’s throat,” Houssien Elouassaki told his brother Abdel over the phone. Afterward, the Army base, which stretched over five hundred acres, became a jihadi training camp. Jabhat al-Nusra controlled the checkpoint to the camp, but Absi’s group trained on its own.

Training lasted twenty days. Each morning began with a ninety-minute run led by a former Egyptian special-forces officer, followed by two hours of tactical lessons with unloaded weapons and simulated attacks, a short break for lunch and prayers, and lectures by Islamist scholars. Lessons were given in Arabic and translated by bilingual jihadis into Dutch. In the evenings, the Europeans took turns on sentry duty.

By late December, the Europeans of the Mujahideen Shura Council were setting up roadblocks on the main road through Kafr Hamra and stopping buses. They rifled through passengers’ belongings, hoping to identify Shia, Christian, Alawite, and Kurdish civilians by small signs: a necklace with a cross, a garment that signified a particular tradition, a picture of Iran’s ayatollah stored on a mobile phone.

Hakim Elouassaki, one of Houssien’s older brothers, joined him in Syria. He explained the routine in phone calls to his girlfriend in Belgium, captured by a wiretap. “We take every unbeliever . . . and we take his money and everything from him,” he said. “I can take money, as much as I want . . . but it must be in the path of Allah.” Only the Sunnis were spared. Hakim stole a gold ring from a Kurd and a laptop from a Christian. His girlfriend later recounted to a friend that, when she offered to send Hakim an iPhone from Belgium, he told her not to bother, because he was “waiting to steal it from an infidel.”