陇山陇西郡

宁静纯我心 感得事物人 写朴实清新. 闲书闲话养闲心,闲笔闲写记闲人;人生无虞懂珍惜,以沫相濡字字真。gender biased images across platforms 4 grabbing attention

from Wikipedia and the Internet Movie Database (IMDb)

A compelling study below, revealing the stark over-representation of men in online images compared to other sources, highlights how this phenomenon can perpetuate enduring gender biases in society. The researchers meticulously analyzed a vast dataset of images across various social categories, uncovering consistent gender biases across different online platforms. Notably, the study demonstrates that online images exhibit more extreme gender associations than text, potentially influencing people's beliefs and biases about gender. The implications are significant, as exposure to gender-biased images could impact individuals' unconscious biases for days, with potential repercussions on real-world gender dynamics and career choices. This research underscores the critical need for further exploration into the mechanisms behind online gender biases and the development of interventions to mitigate their effects in an increasingly image-centric online environment.

*** Ref.

- NEWS AND VIEWS

Gender bias is more exaggerated in online images than in text

Images are an increasingly important vehicle for circulating information online and for grabbing and keeping people’s attention 1 . Writing in Nature , Guilbeault and colleagues 2 detail how online images reflect and exaggerate existing gender bias found in the offline world.

The authors googled a wide variety of social categories (such as ‘lawyer’, ‘doctor’, ‘neighbour’, ‘friend’ and ‘cousin’) and documented that, across these social categories, the number of images representing men was larger than the number representing women compared with similar social categories in other media. Furthermore, the association of these categories with a particular gender (for example, women and ‘art teacher’ versus men and ‘carpenter’) is much stronger in online images compared with online texts, and exposure to these online images can affect individuals’ measures of unconscious (implicit) bias for several days. The findings support the idea that production of online content, in combination with the dynamics of people’s online behaviours, might reproduce and even exacerbate offline patterns related to inequity and a lack of diversity. Because people spend a significant portion of their lives online, these dynamics seem striking.

Guilbeault and colleagues compiled a large data set of 349,500 images — 100 images extracted for each of the 3,495 social categories they studied — and employed thousands of human coders to capture whether those images leaned towards male or female representation (excluding images found of non-binary people). Men seemed to be starkly over-represented in images compared with their representation in a range of other sources (such as in texts, in public opinion and in a census describing employment statistics). What makes the results compelling is that they were not affected by the country from which the images were searched for, suggesting that male over-representation is not unique to Google searches performed in specific countries. Furthermore, the authors replicated their results using images extracted from different sources, such as Wikipedia and the Internet Movie Database (IMDb). This suggests that the observed male over-representation and gender bias in images are consistent and generalizable across other widely popular online platforms.

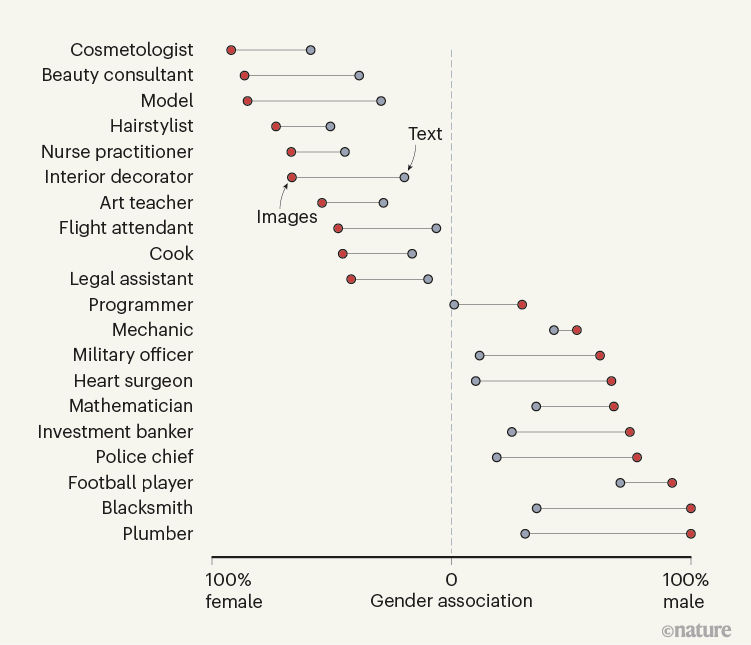

The authors also compared the magnitude of gender bias in images and text by assessing to what extent 2,986 social categories co-occur with references to women or men in various online texts. Using several models to analyse text from a range of sources, they observed a similar association between gender and social categories in text as in images. The gender associations — that is, how each gender is represented in each social category — correlate strongly across both types of media. This suggests that gender associations for the social category ‘art teacher’, for example, are comparable in both images and texts. Yet, the authors found that gender associations with certain categories are much more extreme in images than in text (Fig. 1). For example, observing female ‘art teachers’ in online images was more likely than reading about female ‘art teachers’. Perhaps this finding is not wholly unexpected because, as the authors note, images portraying people naturally signal some demographic information, whereas text can be written in a way that minimizes information on specific demographics.

Figure 1 | Gender associations with social categories in online images compared with online text. Guilbeault et al . 2 searched for 2,986 social categories, such as occupations, using Google Images (for images) or Google News (for text) and measured the frequency with which each social category was associated with one or another gender in the search results. They found that gender association was more extreme for online images than for online texts. The graph shows a selection of occupations across the range of gender association scores. (Figure adapted from Fig. 1a of ref. 2.)

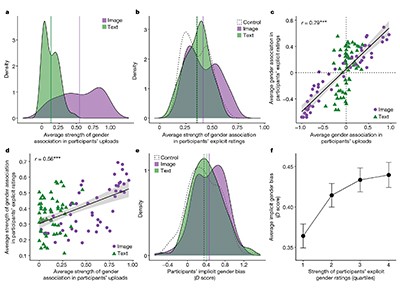

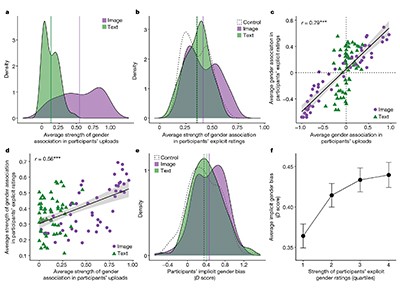

So why does all of this matter? Guilbeault et al . argue that people process images more quickly and images are more memorable than text. Therefore, if online images convey such strong gender associations, they could influence people’s beliefs about gender. To test this conjecture, Guilbeault and colleagues conducted a preregistered experiment in which 450 participants from the United States were organized randomly into three groups: participants searched for specific occupations using either Google News or Google Images, or for phrases that do not describe occupations (such as ‘guitar’) using Google (the control group). Afterwards, the participants completed tasks designed to measure unconscious bias in relation to gender (an ‘implicit association test’). The authors found that the participants who searched for images exhibited stronger gender bias compared with those who searched text or who were in the control group. Most strikingly, gender bias seemed to endure for up to three days after the experiment, but only in those who searched for images.

These results suggest that online images, and hence the online realm, are not only highly gendered, but that this gendered nature might also influence further gender bias in everyday life. Previous work shows that exposure to stereotype-confirming images negatively affects women’s self-esteem and hampers their leadership aspirations, suggesting that gender-biased images can establish and reinforce gendered career choices 3 . Repeating the current study’s measurements of unconscious bias using social categories other than occupations (for example, ‘cousin’) would enable a further exploration of the consequences of strong gender associations in online images. The authors’ conclusions might also be strengthened by conducting the implicit association test with more participants and in different countries, or by further examining conscious (explicit) gender bias.

There are several lingering questions that are essential for future studies to address. What are the exact mechanisms that cause the Internet to become such a gendered environment with respect to online images? Could it be related to particular populations of Internet users, certain design choices or the transfer of existing offline imagery to websites? Once the exact mechanisms are known, what interventions could be put in place to ameliorate those dynamics? Answering these questions is imperative in an age in which images generated by artificial intelligence (AI) will probably become highly prevalent and widespread on the Internet. If these AI-generated images are based on online images that are already gendered, imagery found on the Internet might spiral into becoming increasingly gender-biased.

Nature 626, 960-961 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00291-6